In this interview, Zar Emir tells us about shooting Shayda, the need to be “protected” from the story, finding “joy” in one’s culture, and how universal the film’s themes are.

In these past two years alone, Iranian-French actress, producer and director Zar Amir was involved in three stunning, deeply affecting gems that helped convey her talent both in front of and behind the camera, while shining a light on very important issues. In Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider (2022) – which earned her Best Actress Cannes – she played a journalist determined to stand against a system that seemed to both condemn and condone the murder of sex workers, seen by many as religious cleanses. In Venice favourite Tatami (2023), which she co-directed with Guy Nattiv, she brought us the story of two women – a Judo athlete and her coach (Amir) – whose own country instructs them to fake an injury and retire from the World Championship when politics come into play. Now, she stars in Noora Niasari’s Shayda, out soon in cinemas in the UK & Ireland.

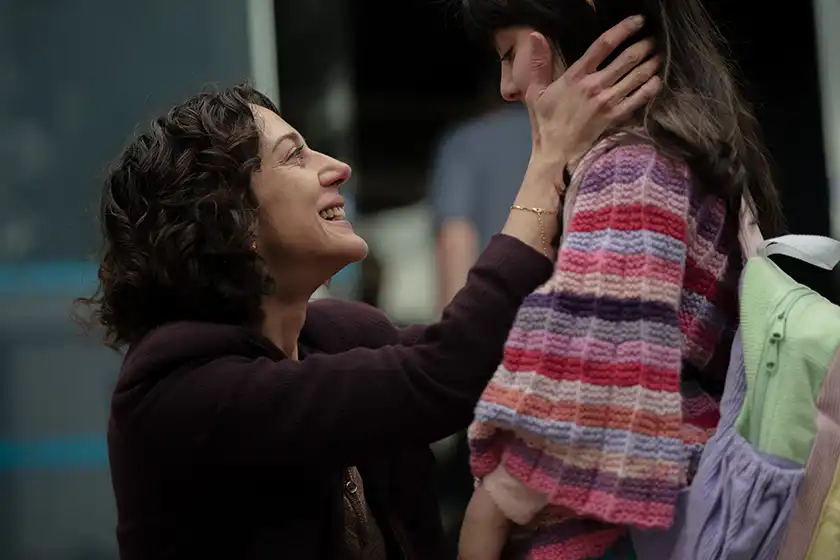

Shayda is a film that’s perfectly in line with the kind of roles Zar Amir has delivered up till now. The story is incredibly relevant, following an Iranian woman who’s been living at a women’s shelter in Australia with her six-year-old daughter, hiding from her abusive husband as she waits for the custody hearing that will change their lives for good. But her husband Hossein (Osamah Sami) wants to take their daughter Mona (Selina Zahednia) back to Iran, and when a judge grants him visitation rights, things become a lot scarier for our protagonist. Shayda is an incredibly tense watch and also a thematically rich one, exploring both a woman and her daughter’s strive for freedom and the context around them, from the cycle of abuse to the judgement coming from Shayda’s own friends and relatives.

A very personal project for director Noora Niasari, who based the film on her own experiences with her mother, Shayda is also a story about solidarity between women – not just a mother and a daughter, but also the various strangers whose different shades of the same experience happened to lead them to a shelter that eventually becomes their family. And just like Holy Spider and Tatami, it’s also another tour-de-force for Amir, who delivers an exceptional performance that will have your eyes glued to the screen for the entire duration of the film.

At the BFI London Film Festival, we sat down for an interview with Zar Amir. Here’s what she told us about shooting Shayda, working with Selina Zahednia and Noora Niasari, the need to protect themselves from the themes of the film, and finding ways to “stay with life” and find the “joy” in your culture.

Zar Amir on her Career and The Stories She Chooses to Tell

I love the projects you’re involved in! Last month I watched Tatami in Venice, and now I’ve just seen Shayda, and thinking back at Holy Spider as well… These are all such important films that people absolutely have to see! How do you find these characters? And also, how do you get rid of them, and all their trauma, when you’ve finished shooting?

Zar Amir: I think I just send this vibe to the universe: that I have to suffer in life, and also in movies! [laughs] I mean, sometimes I get offers or auditions to play roles in entertainment series or movies, which isn’t bad, as they’re usually not Iranian, and I don’t want to be typecast as someone who always has to play an Iranian person. But these stories… They talk to me. They help me get to know myself better, and discover parts of myself.

But also, for example, in Shayda, the way the director, Noora Niasari, approached the character of the father: he’s a guy, but we don’t judge him. And during the movie, I was also discovering this guy, who’s a victim of this patriarchal mindset. My character in Tatami, Maryam, is the same: she’s a loser, but she’s also a fighter and a champion and who…

…Who makes a decision that she knows is wrong, but she does it because she knows she has no other choice.

Z.A.: Yeah. And sometimes all these stories help me overcome my own traumas. [For me to choose a role,] there has to be something there: it has to be a special journey for me as a person, not only as an actor. And after all, all these stories have to be told, you know? Shayda has to be told, and with Holy Spider it was the same. Maybe there’s something in my eyes, or in my vibe, that makes people come to me with these stories, because I’m not actively looking for them. I’m just very open.

At the same time, I also try to be be careful. Yes, all these stories are painful: its all about suffering and trauma, and a many are related to Iranian society or culture. But I try to choose different characters. Maybe you’ll find some similarities between Maryam [the coach in Tatami] and Rahimi [the journalist in Holy Spider] because they’re both fighters, but they’re on very different journeys. And Shayda is something else entirely.

“Staying With Life” in Shayda and Finding Joy in Your Culture

I love that there are two dancing scenes in the film: first, there’s one in a club, where Shayda is scared and we feel so claustrophobic, despite the music singing “Everybody’s Free”. But then, in the second half of the film, there’s another scene where Shayda dances with the other women, and that’s when it feels liberating, at last.

Zar Amir: Yes, because the film is not only about this trauma and suffering. It’s about joy too. A part of the story I really love is when they’re growing sabzeh [lentil sprouts that are prepared for Nowruz, the Persian New Year, as a symbol for life, renewal, and celebration], and getting prepared for Nowruz. It takes place in March, which in our country is spring, but in Australia it’s not; still, the whole ceremony, and the preparation for it, is there. These little moments show how you can “stay with life.”

You can take some parts of your country with you, in some way.

Z.A.: Yeah, but for example, the people in my generation… We never really liked Iranian pop music when we were in Iran. We wouldn’t listen to it, or dance to it. And we’d also never really cook Iranian dishes. But after four or five years living in France, I started to miss it. So I started to find it again: I learned how to cook Iranian dishes. And Nowruz… In Iran, I didn’t always like this ceremony, because you had to be with family: there’d be many family visits and it wasn’t always that much fun. But then, in France, I started to love it: it was a way of staying attached your roots, staying close to the culture, and finding joy in it. Now, I’m the first person who starts preparing things for Nowruz, inviting everyone, cooking for everyone… And there’s Iranian music, and we have fun, you know?

It’s funny, because these days, with how things are going in Iran, we are not allowed to be joyful there. We’re not allowed to dance, or sing, and we’re not allowed to just be together. But Iranian culture, and Iranian people, in the their history… They’ve always found a way to let it go. You know, by just getting together with family, and dancing, dancing, dancing, singing, and being together.

Zar Amir on Working with Selina Zahednia and Protecting Her from The Story

Selina Zahednia plays Mona, your daughter, in Shayda. What was it like to work with her?

Zar Amir: Amazing! She is fantastic. You know, she is an actor. Noora worked with her a lot, for 3-4 weeks, with her assistant, before I got to Melbourne: she was just playing with her, preparing her for the shoot, and getting close to her. But then we met each other, and from the very first seconds, we were friends first. And then, after two weeks of rehearsal, this feeling of being mother and daughter started to grow deeper and deeper. We cried so much the last night of shooting! I didn’t see her after that, and I still miss her.

It’s funny, because you are playing her mother, but you are not even allowed to make her feel you as her mother: she has to know that this is just a game we’re playing.

Oh, of course! Otherwise, I guess she’d be traumatised by the events in the film too.

Z.A.: Yes, we were trying to protect her. That was Noora’s intention from the beginning: protecting Selina from the whole story, and from the violence of it. She didn’t know what was going on, as we were shooting. We just shared those joyful scenes, and then, the times that she was supposed to cry or be in distress, there’d be another story for her, so she wouldn’t know what was actually going on.

We had doubles, but we had to protect the doubles too, so we had many of those, and we were changing doubles so that they wouldn’t know the whole story either, you know?

*Minor spoilers in the next question*

Oh, wow! There’s a very violent scene at some point too, involving the father.

Z.A.: There is, but the child in the scene is not Selina. What made shooting quite difficult was that Selina couldn’t work more than six hours per day, because she’s a minor. So in those six hours, we had to shoot everything we could that involved her. The entire movie is me and her, and my point of view and her point of view, and she was always there. But then, when she couldn’t be there, I was suffering. I was nervous. I couldn’t work with the doubles, because they weren’t her.

But that’s fine, because we had to protect her from the whole story happening there. So, as the crew was preparing the scenes, I was playing with Selina, making it fun for her. And then, I had to cry, and she had to cry, when we were shooting.

Wow! It must have been such a tour-de-force for you to shoot this movie. How long did it take?

Z.A.: Six weeks, but we had a a very long time when we were rehearsing with Selina prior to that. And on top of this, I was also an outsider to a story that reflected Noora’s mother’s actual experiences. I was watching her as a director, but because the whole story is inspired by her own story, she was also overcoming this trauma through cinema. Noora and I had told each other that we didn’t want this film to be a sort of therapy, because we had to protect ourselves too, and we needed to somehow get some distance from the characters. But it was hard.

Shayda‘s Story, Based on Noora’s Own Life, Reflects the Experiences of Many Women and Men Everywhere

How did Noora Niasari approach you for Shayda, and what drew you to the film?

Zar Amir: You know, Noora was so generous to share all these personal family stories with me. Because at some point, it becomes her own story. She asked her mom to tell her story, and then she recorded it. Then, they wrote it. And then, she started to prepare the script: they had a whole process. And then, she shared all these recordings with me, with handwritings, photos, and everything. Then I met her mom in Melbourne, and we got very close. Every night I had a new question, and I could call her if I wanted to, but at the same time, I wanted to play my own version of her. But there was a very rich material to work on, which is difficult, you know?

It’s funny, because her mom told me that I brought too much emotion to the character. “I wasn’t so emotional”, she told me. And I was like, “But you can’t know, because you were living this. Maybe from the outside you weren’t the same person you felt you were on the inside,” but that’s beautiful. You know, somehow I managed, with Noora’s help, to take some distance from the real character.

Noora’s approach to Osamah [Sami], who plays the father, was the same, even though she protected him from the real story too. She didn’t want Osamah to start judging the character, so he didn’t know about the extent of the violence that her mother suffered. Sometimes I was “sneaky” [laughs], trying to give him some information because I had the feeling that he’d get too lost without having some more material!

You kind of feel it from the outside too, as a viewer. I left the screening wanting to know more about the real story behind it, at first, but then I realised I didn’t actually need to, because it’s all meant to be from your character’s point of view.

Z.A.: Yeah, because at the same time, this guy is also a victim of a situation. And all those women in the shelter: they share almost the same story, but they are very different persons. They even hate each other sometimes, you know, but they grow up with each other. Their husbands are the same people, even though they’re also very different persons, because they’re all victims of this system too. This is not just related to Iran: it’s everywhere.

This actually reminds me of another film I saw this year, Inshallah A Boy, which is about a Jordanian woman but treats both men and women as victims of the system. At some point, we even see men telling the woman – who’s about to lose her house and daughter because she’s a widower with no sons: “This is how it works. Why won’t you be reasonable?”. They just don’t understand.

Z.A.: It’s a sick cycle that gets passed down from father to father, from father to son, from father to… anyone, you know? Sometimes even mothers support this. But look at what’s happening in the world right now, from abortion rights in the US to femicide in France…. And these shelters, in Australia: from what I’ve heard, they exist because women really need to have a place where they can protect each other.

When Shayda premiered at Sundance, we had four of five screenings of the film there, and every time I felt so much emotion from the people in the audience. They came out of the screening crying, or sharing their own stories – it wasn’t just Iranians and it wasn’t just women. There were many men too, coming to me in tears and showing real pain, talking about their own parents who were exactly like what they saw in the film, It was so emotional. Unfortunately, we all share this story.

What Shayda Will Mean to Iranian Audiences

Do you think Iranian audiences are going to be able to see the movie?

Zar Amir: Yeah, they’ll find a way, you know?

What do you think it will mean to them?

Z.A.: Some Iranians who don’t live in the country can already see it at some festivals, and now it’s out in Australia too. I think it talks to people. It’s the fact that it doesn’t show a strict stereotype of an Iranian woman, or an Iranian story, but there are all these references to the Iranian culture, like Nowruz, and all these songs: it’s beautiful. and meaning stories spring no rules, all those songs and it makes it beautiful. It doesn’t show “exotic” Iralians, you know? But it’s a joyful and playful watch, at the same time, and I think they’re going to like that.

You know, most of the time for us, when we see all those Iranian films that show this darker side of our society and culture… It’s like putting a mirror in front of us, and people don’t really appreciate it. But I think Shayda has both sides, and it does it in a very nuanced way.

You were saying that you didn’t want the film to be like therapy for you and Noora. Maybe it can still be therapeutic for some audiences.

Z.A.: I guess! It could be.

Thank you for speaking with us!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Shayda will open in select US theaters on March 1, 2024 (with a theatrical premiere at Film Forum) and in cinemas across the UK & Ireland on July 19. Read our review of Shayda below!