Andrew Dominik wants to make a bold statement with Blonde, and Ana de Armas’ astonishing performance as Marilyn Monroe does exactly that.

There are few figures so embedded in popular culture like Marilyn Monroe. Even if you haven’t seen one of her 29 movie roles, you’ve undoubtedly seen photos of her. Holding down a billowing white skirt above a blustering subway grate; in a silky pink gown, descending a red-carpeted staircase and proclaiming diamonds as a girl’s best friend, or even simply just staring sultrily into the camera in a black turtleneck jumper. Hers is an image so iconic, that the term ‘blonde bombshell’ is all that’s needed to conjure it up.

Based on the novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates, Blonde is Andrew Dominik’s fictionalised retelling of the life of Norma Jeane (Ana de Armas) and her tumultuous Hollywood story. It blends fact with fiction, utilising some of the real players in Norma’s life – ‘the Ex-Athlete’, aka Joe DiMaggio, (Bobby Cannavale) and ‘the Playwright’, aka Arthur Miller, (Adrien Brody), Norma’s second and third husbands respectively, as well as her mother Gladys (Julianne Nicholson) – and dramatising their relationships. And it also explores the relationship Norma had with ‘Marilyn’, the “sexpot” superstar alter ego who became a protective shield of sorts, as Norma struggles more and more with addiction and her mental health.

It’s a film that doesn’t advertise itself as a biopic, but rather a deliberately shocking depiction of one of Hollywood’s most iconic women as a desperately sad, traumatised young woman who buckled under the pressure, abuse and expectation piled upon her. It’s a film that courts controversy. Dominik and cinematographer Chayse Irvin take stylistic risks: switching from colour to black and white, depicting a POV shot from inside a vagina and a conversation with a foetus, and strap the camera to actors’ chests for some discombobulating scenes. The sex scenes are explicit, stylised as a metaphor for Norma’s sexual life being public consumption because of Marilyn’s image and the men in her life feeling entitled to the both of them. And it doesn’t shy away from depicting some truly awful moments of sexual and domestic violence.

But it somehow doesn’t feel exploitative or unnecessary, just upsetting and not particularly enjoyable. And yet that’s not an insult. The film is meant to make you feel that way. It feels designed to circumvent preconceptions you had about Norma, about Marilyn, and toss them aside to deliver a portrait of a fragile, unstable woman who was consistently the subject of physical, emotional, financial and psychological abuse. Norma’s life was not a happy one, for the most part, and Dominik is content to visualise that as plainly as possible.

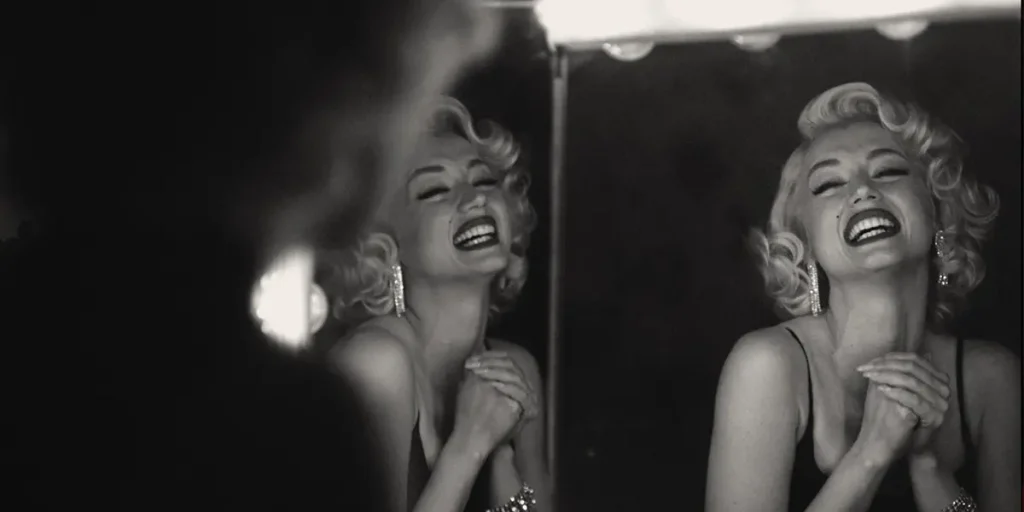

As Norma/Marilyn, Ana de Armas is absolutely astonishing. Coquettish, sexy and heart-breaking all at once, she’s a ferocious presence on screen. During the recreations of some of Marilyn’s most famous silver-screen moments – the aforementioned ‘Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend’ performance, in particular – the resemblance between them is almost uncanny. When she’s watching herself in the theatre, the camera slowly pans back so that her upset, frightened face is surrounded by a sea of smiling spectators.

It’s a wonderful visualisation of her vulnerability, of her feeling adrift and the role ‘Marilyn’ plays in Norma’s life. She’s a shield, an armour that Norma calls upon to face the expecting public. Hordes of men jeer and leer at her as she auditions, as she performs, and as she simply walks into a building or sleeps on a plane. Her sexuality has been commodified, and one of the film’s saddest moments is when Marilyn walks past a jittering mass of reporters, whose faces distort and their yelling becomes a dissonant, echoing noise, and she simply smiles and waves. Because it is expected. Because she must. When she’s crying, mourning and desperately unhappy, she prays in the mirror to be helped, to be saved. And her reflection straightens up, cocks her shoulder and smiles that ‘Marilyn’ smile. It’s a gut-wrenching performance from Norma and de Armas, and highlights how Marilyn is the glue keeping Norma together, but that glue is slowly coming unstuck too.

Dominik posited the question of how an “unwanted child” transforms into “the most wanted woman in the world”, and Blonde tells us that it was a traumatic journey, and one that was never fully successful. Norma struggled not to feel like that ‘unwanted child’; visiting a hospitalised Gladys who doesn’t recognise her and tearfully clutching at her middle, calling her husbands ‘Daddy’ and being terrified people won’t like her. The Norma on screen is a far cry from the Marilyn of public culture, and that’s precisely the point.

Dominik – and, to an extent, Oates – are utilising the figure of Marilyn Monroe to tell the story of how fame can ruin lives and how being a sex symbol does not entitle anyone else to your sexuality. Blonde tells the story of a young woman’s tragic life in a way that shows the grit beneath the glamour, and wants you to feel uncomfortable for having witnessed and partook in it. And it succeeds.

Blonde premiered at the 2022 Venice Film Festival on September 8, 2022, and will be released globally on Netflix on September 28.

Read the complete 2022 Venice Film Festival line-up, discover the “Venice Immersive” virtual reality strand of the programme, and take a look at our list of films to watch at Venezia 79!