To celebrate Asian Heritage Month, we look at the 10 greatest East Asian films ever made, ranked from worst to best and with selections ranging from the 1950s right up to 2019.

It has been an absolute delight to sift through the works of directors no longer with us, such as Akira Kurosawa or Yasujirō Ozu, as well as those still working and still entertaining us today, like Bong Joon-ho and Hirokazu Kore-eda. From the subtle, family-centric tales of Japan to the captivating, sensual romances from Thailand or Hong Kong, East Asian films are a collective behemoth that really can’t be restricted to a simple Top 10 ranked list, but that’s exactly what we have tried to do. There are plenty (plenty) of honourable mentions which could make up several lists of their own, but, for the time being, that will have to wait. Read our rankings below and then swiftly watch them all!

10. TRAIN TO BUSAN

(Busanhaeng)

2016

Director: Sang-ho Yeon

Writers: Joo-Suk Park & Sang-ho Yeon

One of the greatest zombie films of all time, from East Asian cinema or otherwise. South Korea’s high-concept action horror sees a train heading to – you guessed it – Busan suddenly caught in the midst of a viral outbreak which sees anyone infected turn into a flesh-eating, fast-moving zombie. The film’s measured opening centres on Seo Seok-woo (Gong Yoo) and his young daughter, Seo Su-an (Kim Su-an), establishing their strained and distanced relationship early on.

As the train pulls out of Seoul Station, a train attendant exhibits the first signs of infection, almost instantly transforming into a rabid cannibal and thus starting one hell of a train ride for all the passengers onboard. If a two-hour film mostly set on a train – bar a detour into another station – sounds dull or short of ideas, think again.

Train to Busan explodes with intelligent set pieces that will raise your heart rate with their intense action but equally has slower moments that will have you biting your nails thanks to the excruciating tension. Add in a horde of zombies that move with powerful speed à la 28 Days Later (2002) and you have a masterpiece of East Asian cinema and one of the very best horror films around.

9. STILL WALKING

(Aruitemo Aruitemo)

2008

Writer & Director: Hirokazu Kore-eda

Japanese director Kore-eda is, in very simple terms, a direct heir to Ozu, his fellow countryman who established himself as one of the best directors in East Asian cinema in the mid-1900s. Still Walking is the film with the most obvious relationship to Ozu’s work, a familial portrait that presents complex, emotional questions and no easy answers.

This subtle, human film follows a family over a day or so as they meet up, as they do every year, to commemorate the death of the eldest son. There is humour, levity and simple enjoyability in their interactions, but also a great deal of pain and unspoken frictions between each member of the family. Kore-eda never simplistically spells out these emotions, instead letting his reserved, static camerawork and witty, multifarious script do the talking.

By the end of Still Walking’s near two-hour runtime, a surprising amount has happened but very little has been resolved, which is what makes it so pleasing. Life isn’t always simple as it can be in the movies and resolution cannot always be so easy to come by. Kore-eda knows this full well, and Still Walking is the best example of him showing that.

8. PRINCESS MONONOKE

(Mononoke-Hime)

1997

Writer & Director: Hayao Miyazaki

A ranked list of the greatest East Asian films would not be complete without a Studio Ghibli film, and, whilst Spirited Away (2001) might be a surprise omission, Princess Mononoke just about pips it to a spot. Released in the late 1990s just prior to the immense international recognition for Studio Ghibli that came from Spirited Away, Hayao Miyazaki’s epic is fantastical but also steeped in realism, and has some of the darkest moments and themes seen in his or the studio’s work.

For one thing, beheadings are a frequent sighting in this animation but there are also intelligent and hugely scathing commentaries on deforestation and the killing of animals. The importance of environmentalism is underlined multiple times, with all of this told through a real period of Japanese history but incorporating various fantasy elements. Princess Mononoke harbours almost everything that audiences love about Studio Ghibli’s works: serious adult themes, breathtaking animation and world-building, pure escapism and a memorable original score. East Asian cinema is extremely lucky to have a studio such as this in their midst.

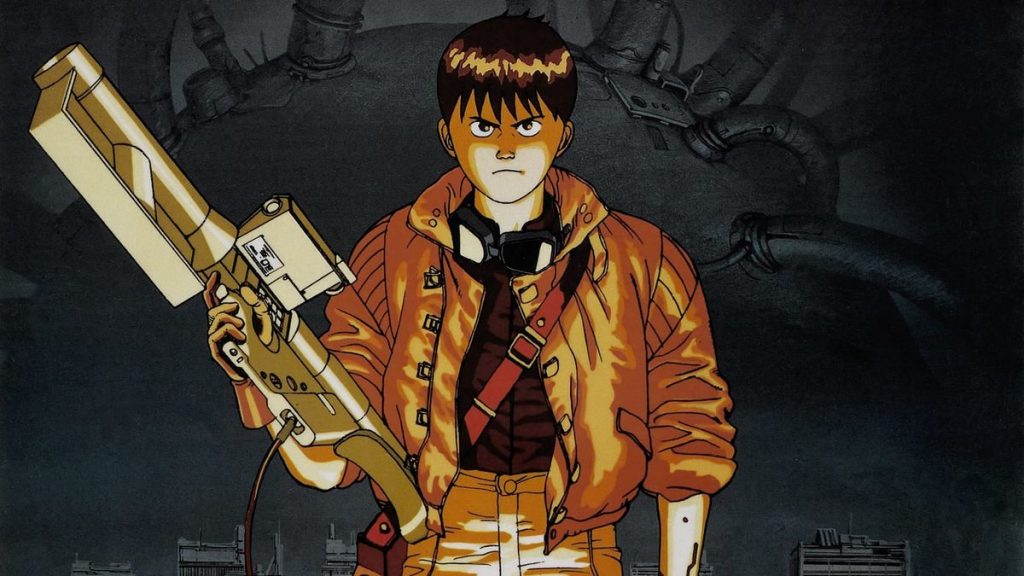

7. AKIRA

1988

Director: Katsuhiro Ôtomo

Writers: Katsuhiro Ôtomo & Izô Hashimoto

The second of two animated films in this ranking, East Asian classic Akira is a monumental and otherworldly journey of chaos (in the most beautiful, neon-kissed way). Katsuhiro Otomo’s crowning achievement is set in a futuristic Neo-Tokyo in 2019, a city ravished by another world war and dominated by lawless biker gangs. It opens as it intends to go on: with a breathless bike chase through the gleaming, dystopian, cyberpunk streets, complete with explosions galore and dynamic direction. Following an accident at the end of this chase, one of the main characters acquires telekinetic powers, which sparks the rich and intelligent narrative that unfolds unpredictably and speaks to themes of world wars, collective fears of the populace, nuclear weaponry and more.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about Akira is its rich world-building; it’s hard to think of another futuristic dystopia being created this vividly on screen, perhaps only matched by Blade Runner (1982). Akira does take influence from films such as this one, but it never feels derivative, and in turn it became one of the most influential pieces of work in its own right, in both the animated and science fiction genres. This is East Asian anime at its most adult and most memorable.

6. IN THE MOOD FOR LOVE

(Fa Yeung Nin Wah)

2000

Writer & Director: Kar-Wai Wong

Wong Kar-wai’s sensuous, achingly beautiful tale is not just a highlight of East Asian films, but also one of the very best romances ever committed to screen. Set in British Hong Kong in the early 1960s, In the Mood for Love follows the flourishing but forbidden relationship between Su Li-zhen and Chow Mo-wan, played respectively by East Asian cinema heavyweights Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung, and forbidden because both are already married. Living as neighbours in a cramped apartment, their romance is comprised of longing glances, fleeting conversation and brief moments of passing each other in the hallway and street.

Wong, known previously for his fast-paced, inventive direction in films such as Fallen Angels (1995) and Happy Together (1997), instead opts for a slower, more measured approach, enhancing the intense but repressed emotional and physical feelings the characters are harbouring. Su Li-zhen is like an angel in her ravishing, elegant costumes and the stunning cinematography captures the rain-drenched, hazy feel of the Hong Kong streets perfectly. East Asian films have rarely been this aesthetically intense, making In the Mood for Love a must-have in this ranked list.

5. HARAKIRI

(Seppuku)

1962

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Writers: Yasuhiko Takiguchi & Shinobu Hashimoto

Head back now through the decades of East Asian films to 1962 and experience this masterful work by Masaki Kobayashi. Focussing on the act of seppuku – also known as harakiri and quite literally meaning ‘cutting the belly’ – within samurai culture, Harakiri doesn’t follow the same formula or themes of other Japanese samurai films from the time. Kobayashi does not present the warriors in this film as noble men but rather as petty, false people who lack real honour, despite all their protestations. He deconstructs and mocks the notion of tradition as well as highlighting the brutality of the suicidal act of harakiri.

Slow zooms and steady camerawork capture the time and place tremendously and allow the characters and script space to come alive. Tatsuya Nakadai’s lead performance is a wondrous mix of humour and scathing remarks. Harakiri firmly deserves its place in the top five of this ranked list, a piece of work that stands not just as one of the finest East Asian films, but as one of the best worldwide.

4. PARASITE

(Gisaengchung)

2019

Director: Bong Joon Ho

Writers: Bong Joon Ho & Jin-won Han

The most recent film on the ranked list but one of the most deserving. Bong Joon-ho’s scathing satire, Parasite, is the sort of special film that only comes out a handful of times across a decade. It managed to set countless records, perhaps most memorably in becoming the first non-English language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, and became a huge success story for East Asian films. Widely regarded as the greatest film of the 2010s, Parasite will be talked about fervently for years and years to come.

Bong’s greatest work – only almost matched by Memories of Murder (2003) – is a fierce, cutting commentary on class in South Korea that has obvious parallels to countries around the world. The combination of genres on show is staggering; comedy becomes tragedy, and vice versa, with sprinklings of horror, family drama and thriller elements thrown in for good measure. The transition between each is seamless. Parasite’s caustic tale is enhanced by perfect screenwriting, unbelievably well-thought-out direction and cinematography and a sumptuous ensemble cast.

Over time, Parasite may deserve to rise higher in this ranked list. Such was the much-deserved hype around Parasite, you have probably already seen it. If not, seek it out immediately. And if you already have, watch it again: there is so much to uncover in this complex, captivating tale.

3. LATE SPRING

(Banshun)

1949

Director: Yasujirō Ozu

Writers: Kazuo Hirotsu, Kōgo Noda & Yasujirō Ozu

When one thinks of East Asian films, two names will inevitably crop up more than most: Japanese directors Yasujirō Ozu and Akira Kurosawa. It goes without saying, then, that both have films in the top three of this ranked list, but the more challenging aspect was deciding which films of each director should make it in. Late Spring is the choice for Ozu, a film only just beating out another of his masterpieces, Tokyo Story (1953).

East Asian films, and in particular Japanese films, have had a long-standing affinity with familial dramas, and Ozu is the prime embodiment of this, a man whose films almost always focus on families in society as well as male and female roles within these structures. The Ozu trademark of stationary camera shots placed at a low height is here in Late Spring to absorb and enjoy, giving the realistic acting and writing ample space to breath.

The focus in this film is on Shukichi and his adult daughter, Noriko, played by Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara respectively. Society’s expectations on Noriko as a young woman to marry and leave home are delicately but effectively observed and the film is relatively subtle until a devastating, emotional finale that swells with power. It is Ozu at his best, creating a staggeringly human piece of observational cinema.

2. A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY

(Gu Ling Jie Shao Nian Sha Ren Shi Jian)

1991

Director: Edward Yang

Writers: Hung Hung, Mingtang Lai, Alex Yang & Edward Yang

Weighing in at a mammoth 237 minutes, A Brighter Summer Day is another of these East Asian films that is difficult to put into words, such is its epic but highly personal power. Released in 1991 by the late Edward Yang, one of the most influential directors from the ‘Taiwanese New Wave’, A Brighter Summer Day is inspired by a tragic murder story which garnered immense coverage within Taiwan during the 1960s.

Aside from its compelling narrative, intricate structure and well-rounded characters, Yang’s film is one of the greatest examples of this ‘New Wave’ of cinema which emerged during this time, a movement combining intense realism with genuine portrayals of Taiwanese people and society, as opposed to the melodramas or action films that had usually been produced prior to this. Loss of childhood innocence, societal violence, Westernisation, loss of identity, authoritarian rule, rebellion against the state: all of this and more are painstakingly stitched together in Yang’s magnum opus.

Don’t be put off by the runtime; instead, give yourself to this film and be transported to another world, another time. And when it’s over, you’ll want to sit through this complex piece of East Asian cinema again almost immediately. It is scarcely believable that a film of this magnitude and power exists.

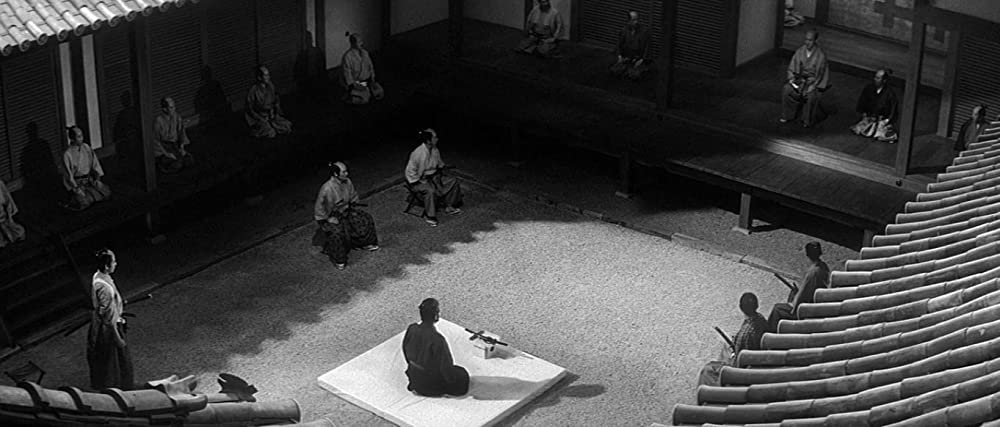

1. SEVEN SAMURAI

(Shichinin no Samurai)

1954

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Writers: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto & Hideo Oguni

If you were worried by the lack of Kurosawa films on this list, worry no more. The late Japanese director was not just a legend within East Asian cinema but throughout the whole world; his legacy and influence can be seen in Western cinema in works by Hollywood greats such as Steven Spielberg and George Lucas.

Seven Samurai might be shorter than the second film in this ranked list – notching in at a measly 207 minutes – but it remains the biggest, most epic piece of work here. Seven samurai (you guessed it) are hired by a small village to defend their crops from bandits, who regularly return to steal their harvest. That is Seven Samurai in a reductive, simplistic nutshell, and yet Kurosawa manages not only to draw a three hour plus film out of this, but also ensures it is captivating at every single moment and full of believable – and more importantly – likeable characters.

Seven Samurai pits good against evil and lets the action run riot, a structure we have seen in numerous other English-language epics, such as the Star Wars series or The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Kurosawa’s skill at filming absorbing action whilst still keeping things clear for the audience is at its fullest potential in Seven Samurai. Whilst other East Asian films in this ranked list value quietness and tranquillity in their approaches, Seven Samurai screams with action and intensity. Kurosawa’s best, East Asian cinema’s best, and maybe even the world’s best.