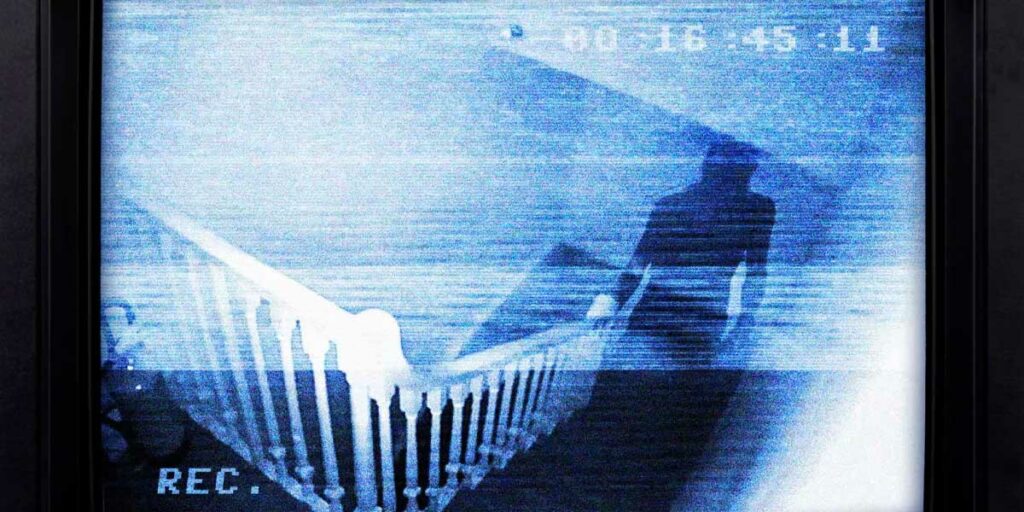

Shudder’s The Found Footage Phenomenon is an interesting if ultimately standard documentary that explores the underground subgenre of found footage.

As the medium of film grows each year, the goal has changed to make them as big and grand as possible. Whether it’s massive blockbusters or expansive cinematic universes that tie a large series of films together, the medium has evolved to essentially “go big or go home”. However, there are many who do not subscribe to this rule and have shown their reluctance to fall into the Hollywood studio system in various ways. One of which is the found footage movie. A subgenre that has gone through highs, lows and a little something in-between. With Shudder’s The Found Footage Phenomenon, the film explores the subgenre and how despite its numerous falls from grace, it manages to still exist as this underground and personal avenue for creators to create bold stories.

In general media consumption, there’s always been a distinct line between what is reality and what is fiction. Whether its a sci-fi story like Star Wars or even something that mimics reality somewhat like television dramas such as This Is Us, the audience and the filmmakers have an understanding with each other that the events on screen are not real and no attempts will be made to have the audience believe otherwise. With found footage, there’s a different form of understanding that much of The Found Footage Phenomenon bases itself around and that’s the idea of making the audience believe in a lie told by the filmmakers that paints the image for the piece of media they are about to watch. The lie being that what you are watching on screen is as real as the life the viewer is currently living no matter how fantastical it may get.

Early in The Found Footage Phenomenon, the documentary explores the idea that found footage is merely the evolution of our desire to see media closely replicate what is around us. The 1897 novel “Dracula” tells its narrative through a series of documents intended to sound like they come from “real” people recounting a supposedly true story and the 1938 Orson Welles radio broadcast based on War of The Worlds used the concept of an alien invasion to invoke fear in its listeners. Both pieces of media and literature came to their chosen mediums to tell a story that the audience could believe was as real as themselves as a bold way to deliver horror and tension. Something that found footage then took on board as both the world and the medium of film began to evolve.

Much of the beauty of found footage comes from its willingness to take on the evolving world around it. As The Blair Witch Project used the rising power of the internet to tell its story within the confines of reality in 1999 and Host utilised the collaborative isolation we all undertook during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the subgenre was always able to transform itself into whatever its filmmakers needed whilst applying the same tricks. As the Hollywood studio system locks itself up and relies on the current trends and the same old formulas and characters to make their films, found footage has always existed as a place for the tossed aside filmmakers to find a voice. You don’t need the newest hi-tech film camera to make a film like Paranormal Activity.

All you need is a home camera and a strong idea that will create the thrills and authenticity you want for a strong film. There are multiple points in The Found Footage Phenomenon that delves into the idea of media being used to explore the darkest thoughts that filmmakers have in relation to the world and our general media consumption. The second boom of found footage with Paranormal Activity came in a post-9/11 world, the rise of Youtube making the act of recording yourself a normal everyday task and the popularity of torture porn movies such as Saw and Hostel. As our media palettes sought gore and the insistence of bringing our fictional work closer to reality than ever, a space existed for the subgenre to thrive that even the larger Hollywood studios noticed.

For much of The Found Footage Phenomenon, we navigate through a timeline of sorts through multiple noteworthy found footage movies such as Paranormal Activity and The Blair Witch Project as well as lesser-known films in the subgenre that were either direct inspirations of these influential films or films that were indirectly damaged due to unintentional similarities. Many of the filmmakers covered in the documentary all come to very similar understandings of what the subgenre means to them and that’s an attempt to blend film and the real world closer than ever. Despite the shared understanding, the underground nature of found footage means that there are certain debates over where or how it began in the first place. The Last Broadcast is a film seen as the first found footage film before The Blair Witch Project was a massive success in 1999 but with films such as 1992’s Ghostwatch and 1980’s Cannibal Holocaust also entering the conversation, the debate becomes muddled and somewhat falls on writer and directors Sarah Appleton and Philip Escott not to create a concrete answer but rather explore the general space and debate itself.

As found footage went through multiple forms and evolutions over the years, there’s admittedly a lot to cover that The Found Footage Phenomenon simply can not over a runtime of just under a hundred minutes. Although the documentary does a competent job of exploring the subgenre and allowing many of its filmmakers to explore their passion and intent to create truly radical and sometimes even heavily political works, it struggles to truly articulate at times why the subgenre is specifically so special or as the title suggests, a phenomenon. Much of the documentary falls into making the same admittedly interesting yet repetitive point of the audience’s willingness to deny themselves the ability to discern reality from fiction when a filmmaker asks them to. The film also expects the viewer to already have an extensive knowledge of the subgenre to the point where it expects you to have seen many of the much lesser-known films covered here, leaving it as a bit of a missed opportunity to work both as an explanation of why the found footage subgenre deserves far more respect than it’s given and why these films should be tracked down and watched.

Where The Found Footage Phenomenon does shine however is when it does offer those perspectives from the lesser-known filmmakers associated with the films that the documentary covers. Hearing the director of 2011’s Megan is Missing speak about the film’s lasting success despite its strong negative reaction as TikTok users discovered its content and the passion that some users had for the film is deeply fascinating and a strong example of why this subgenre can be incredibly effective. Much of the success in found footage does not lie in the box office takings but rather in the visceral reactions you can create for an audience who comes on board with the lie that the filmmakers create.

The Found Footage Phenomenon may not work completely for those who are new to the subgenre or even have somewhat of a distaste for it overall. However, it does work as a space for many underappreciated or misunderstood filmmakers to discuss why or how this subgenre gave them the creative template they needed to create truly bold and radical works. Although found footage as a subgenre will disappear from the public eye from time to time, the flame of its creativity and passion is never extinguished.

The Found Footage Phenomenon premiered on Shudder on May 19, 2022.