Zarrar Khan’s In Flames utilises horror stylings to explore how oppressive patriarchal violence literally and metaphorically haunts the women of Pakistan.

In Flames, written and directed by Zarrar Khan, is a horror film about the horrors of reality. It explores the oppressive order of Pakistan’s patriarchy – both the literal violence and the metaphorical ghosts of it – and how it haunts women who dare to exist outside of a ruling male thumb. It’s a film that relishes in the uncanny, in creating tension and utilising the stylings of the horror genre to explore the dangers of a world where women are constantly indebted to the men around them, expected to acquiesce, and struggling under the all-too-common weight of familial violence.

In Karachi, Pakistan, the lives of young medical student Mariam (Ramesha Nawal), her mother Fariha (Bakhtawar Mazhar), and her younger brother Bilal (Jibran Khan), are rocked by the unexpected death of her grandfather. Facing having to fend for themselves in an oppressive patriarchal society under a mountain of debts, the sudden reappearance of Uncle Nasir (Adnan Shah) is welcomed by Fariah, who gratefully accepts his offers of help. But Mariam doesn’t trust him, and she warns her mother that nothing is given for free.

Outside of their cramped apartment, Mariam meets fellow student Asad (Omar Javaid), with whom she beings a courtship, and the pair sneak away to the beach for an afternoon together. But on the way home, tragedy strikes, and Mariam’s world starts to crumble. Her childhood asthma returns with a vengeance, she’s seeing ghostly apparitions and having terrifying nightmares, and Nasir is after their home. The walls are closing in, and Mariam and Fariha must fight a society that sees women inherently indebted to men in order to survive.

Zarrar Kahn’s film is a genre hybrid that blends the horrors of the supernatural with the horrors of mundanity. It’s a film that uses ghosts as an allegory for the patriarchy itself, with the men in Mariam and Fariha’s lives still exercising control over them even after their deaths. They are manifestations of the trauma inflicted upon Mariam and her mother, haunting them as nightmarish apparitions as they navigate a world that offers little respite. In Flames is also poignantly grounded in reality, despite its supernatural elements, because this is very much indicative of the real-life experiences of thousands of women in countries like Pakistan.

It’s a film that relies on keeping its audience off-kilter, leaning into the feelings of claustrophobic fear and paranoia that plague Mariam and Fariha. Their world is one in which nothing is given for free, and even acts that are seemingly kind – like a lift home through the bustling chaos of the city at night or paying off a debt – come with a price. For the true horrors of In Flames are the intentions of men. Fear, anxiety and suspicion are cloyingly present throughout the whole film, and Khan isn’t afraid to languish in those feelings and create discomfort.

Also crucial to maintaining that oppressive, dangerous mood is Aigul Nurbulatova’s cinematography. There are some truly stunning moments of juxtaposition in the film, like the tranquillity of the beach serving as the scene of Mariam’s happiness, paranoia and trauma, as well as the cacophony of discordant city noise travelling through the walls of their cramped apartment, emphasising that feeling of claustrophobic fear. It all plays effectively into the horror stylings, and In Flames feels really well balanced because everything is so thoughtfully paced.

At little over 90 minutes, Khan – alongside editor Craig Scorgie – fills every scene with intrigue and emotion, even if there isn’t much physical action taking place. The tone isn’t always successful in its consistency – the montage of Mariam and Asad’s blossoming romance is a little too jarringly sweet and overlaid with a somewhat distractingly hazy filter – but it’s a minor issue because the film doesn’t linger there.

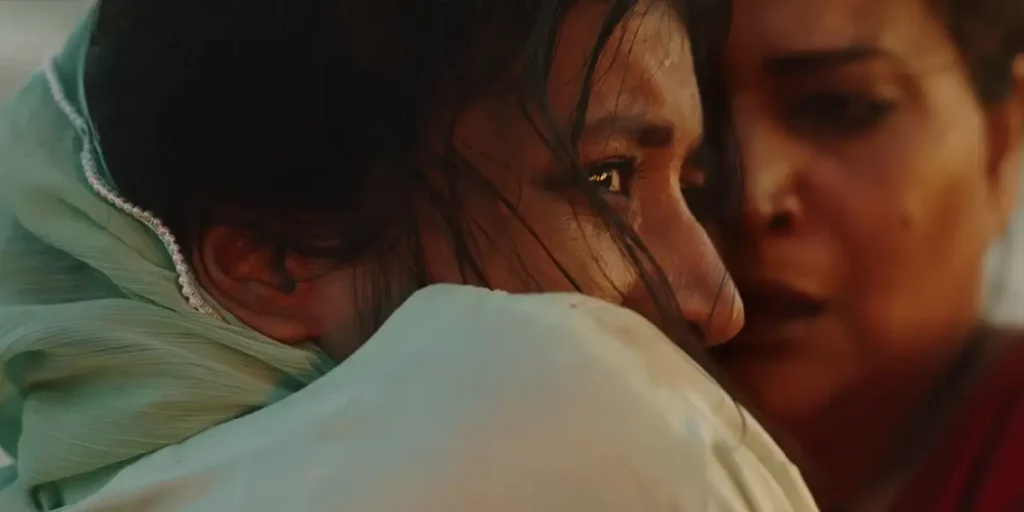

In Flames is a film about trauma, grief, isolation, patriarchal society, healing and resilience. Khan utilises Nawal and Mazhar’s fantastic performances to navigate these themes, all crammed together in that tiny apartment. The relationship between mother and daughter is somewhat fractured and distant at the beginning, but they must work together to overcome the forces – both supernatural and not – that seek to oppress them. Nawal conveys Mariam’s fear so delicately, her shifting expressions showcasing Mariam’s internal struggles as she fights against a world that is closing in around her. And Mazhar’s shift as the film goes into its third act, changing from the meek and trusting figure Fariha appears to be into the strong woman that has raised such a daughter, is a really effective counterpoint to Mariam’s descent into vulnerability.

Their stories, together and individually, are almost intrinsically woven into the fight for women’s rights, and it feels like that’s exactly the point Khan is trying to make with In Flames. It’s an astonishingly confident film that poignantly uses the horror genre to expose the horror of Pakistan’s patriarchal realities. It’s a film about the legacies of violence, of female oppression, and of the nightmarish effect it has on women like Mariam and Fariha.

In Flames will be released in US theaters on April 12, 2024. Read our reviews of Tatami, Shayda, and Inshallah A Boy.