In Yorgos Lanthimos’ sophomore feature, Dogtooth, a mother and father’s warped parenting brings dark and dangerous results.

The tension and unease of Yorgos Lanthimos’ (The Lobster, The Favourite) second feature film, Dogtooth, is established instantly and never dwindles. Its 97-minute runtime may be brisk in length, but the film is far from a breeze: the difficult subject matter of abuse is consistently horrifying, amplified by Lanthimos’ rigid compositions and warped angles. With this clinical, methodical approach, one of the world’s finest directors crafts a tale that is as disturbing as it is engrossing. Perhaps most uncomfortable is how Dogtooth remains as grounded in realism as any Lanthimos film, even when the surrealism of this twisted family world is shown in all its stark detail.

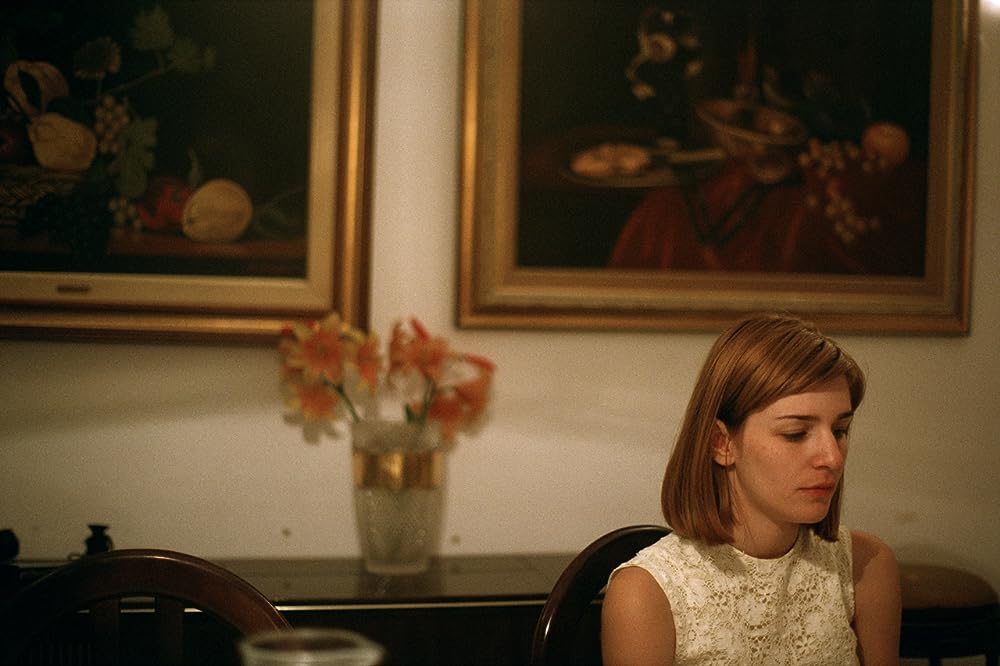

In a quiet Greek neighbourhood, a mother (Michelle Valley, Singapore Sling) and father (Christos Stergioglou, Unfair World) live at home with their three adult children (Angeliki Papoulia, Christos Passalis and Mary Tsoni). However, these young adults aren’t just recent graduates applying for jobs, or 30-somethings returning home after a messy breakup; they have never left their house, which is a large structure set in a compound with high walls and large gardens. From this prison-like location, their lives are strictly controlled by their father and, to a lesser extent, their mother. Only when they lose a dogtooth, their parents claim, can the children leave the compound.

Just as the father and mother control every minute detail of their children’s lives, Lanthimos and his cinematographer Thimios Bakatakis (The Killing of a Sacred Deer) do the same for every shot and composition. The strict framing reflects the parents’ iron fist regime, the director moving from scene to scene with unflinching abruptness. And yet despite this control, the off-kilter camera angles and partial framing of characters hints at an authoritative but fragile and distorted world. How long can such a repressive rule be enforced? Actions are often only partly witnessed as this family’s tragic world produces secrets and lies. Unease and dread engulf Dogtooth, hinting at the tortured mental and physical states of the siblings, and giving us as viewers an enrapturing but deeply disturbing experience.

Lanthimos infuses average domesticity with dread, depicting a suburban setting ripe with surrealism. It’s a bleak marriage of settings and tones that gives way to unforgettable imagery—blood splatters a fridge door or a smashed-out tooth sits in a sink—but one that also, more deeply, allows Dogtooth’s commentaries on authority and freewill to play out. The siblings’ search for freedom as adults begins to emerge, underlining the fact that this domestic setting won’t last forever. Dogtooth’s portrayal of parenthood is extreme, albeit applicable to some real-life cases, and Lanthimos keenly questions what acceptable methods of parenting are. The domestic backdrop gives credence to these thematic explorations and amplifies their resonance.

In Dogtooth, the dog doesn’t just get a basic titular nod: throughout Lanthimos’ film, the parallels between this animal and the three siblings are consistently and provocatively drawn. The father visits a dog handler early on in the film to check on a family pet and is told that it will require six steps for it to become fully obedient. The parallels strengthen from here. Cats are the enemy, the father tells his children, and will kill them if they leave the compound. Meanwhile, the three siblings and even the mother are made to bark like dogs.

Most disturbingly, oral sex—referred to simply as “licking” by the children—is performed in the way a dog might lick a bone. Via the father, Lanthimos blurs the line between humans and animals, reinforcing the commentaries about the dangers of authority, and how it can diminish the subjugated to animalistic roles. From birth, these children have been told certain things, made to live in a specific way, and to them, nothing is wrong with their homelife. The bestial actions they are forced to partake in feel normal, but eventually, their minds question them.

In the 2010s, Lanthimos became more widely known for his English language films The Lobster (2015), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), and The Favourite (2018). All bear his now trademark surrealist touches, but none are quite as disturbing as Dogtooth. It might occasionally place value on style or shock factor over substance, but this Greek gem is a unique cinematic experience that is as hypnotic as it is repulsive. If released now, 14 years on and in light of Parasite‘s recent Academy Award success, it may well have been the foreign language Best Picture Oscar winner we had all been waiting for.

Dogtooth is now available to watch on digital and on demand. Watch Dogtooth!