Vertigo is a thrilling masterpiece that expertly plants every seed before unveiling its true twisted purpose, earning its place as a nearly-undisputed classic.

It’s hard to discuss the history of film without bringing up director Alfred Hitchcock, and it’s even harder to talk about Hitchcock without bringing up what many consider his magnum opus, Vertigo. This psychological thriller came out in 1958, and to this day it remains one of the most acclaimed films of all time. Which means I know I’m not alone when I say it’s one of my personal favorite movies as well. Its intense acting, compelling characters, unforgettable visuals, and dark, twisted storytelling make Vertigo a masterpiece of a thriller. I’ll be treading lightly when talking about the specific reasons why, as I don’t want any of the many surprises this film has to offer ruined for anyone who hasn’t seen it yet.

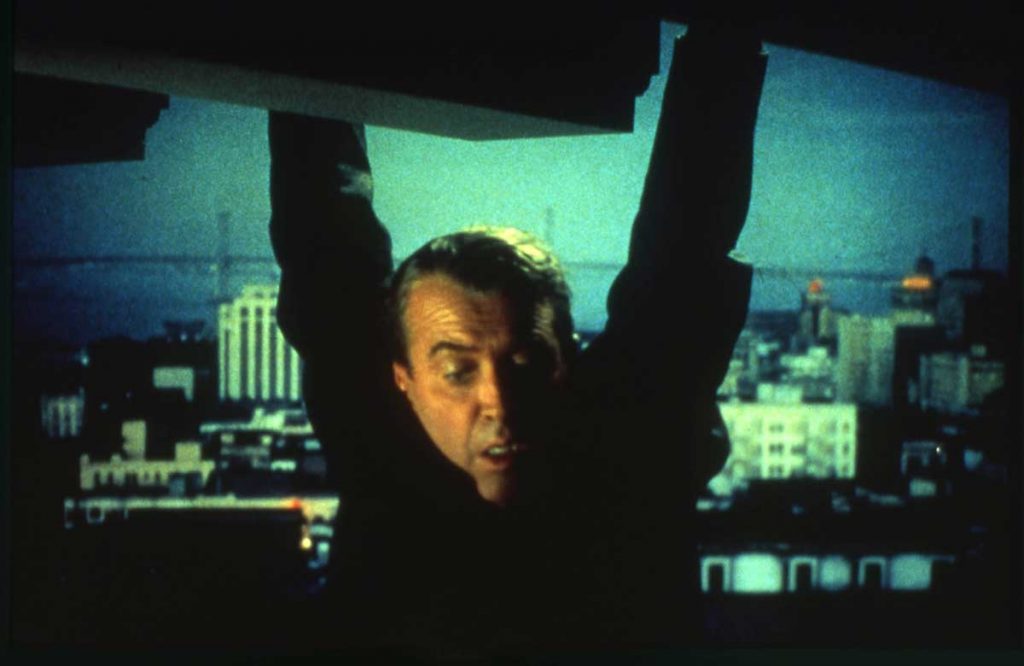

Vertigo stars James Stewart as John “Scottie” Ferguson, a former police detective who suffers from acrophobia and vertigo. Sometime after going into early retirement, Scottie is hired by an old friend (Tom Helmore) to investigate his wife Madeleine (Kim Novak), who he claims is behaving strangely. This leads Scottie to the unraveling of many layers surrounding Madeleine’s family history, the possibly of her being haunted or even possessed, a quickly-developing romance with her, and ultimately a big reveal that everything is not what it appears to be … and honestly, to say any more would potentially ruin the fun for the uninitiated. Part of what makes Alfred Hitchcock such an incredible storyteller is how well he plays the long game with his movies and what they’re really about. He draws you in with a story that you think has established its basic setup, even if you’re not sure what it’s amounting to. But then, he completely flips the script with some shocking turn or unexpected reveal, changing the story into something else entirely.

Obviously so much credit for that in Vertigo’s case has to go to the source material, as well as Alec Coppel and Samuel Taylor for penning the adapted screenplay. But it still takes a master director like Hitchcock to portray that material and create a genuinely good mystery that hooks the viewer in very early on. The level of detail and the degree to which Scottie finds himself involved and continues down the strange rabbit hole before him, all has you convinced that solving this great mystery is the endgame of the film. The acting from every major character is so good and the writing for them feels so well-developed that it’s hard to pick up on the fact that what you’re seeing in front of you isn’t what you probably think it is. A lot of movies have used tactics like this to bait-and-switch the viewers, but Vertigo remains one of the best of such executions even over sixty years later.

James Stewart (Rope) brings a lot of charm to his performance as usual, portraying what seems like a naïve, likeable, sympathetic man who’s been somewhat beaten down personally and professionally by his acrophobia. But you hope that he can achieve a new sense of fulfillment by helping out in this latest investigation, bringing peace to Madeleine as well as himself. Though his more emotional decisions and motivations at first feel a little off – namely, it’s a little strange how he falls in love with Madeleine given how little time they know each other and what they’re trying to accomplish together – you’re still with him as he tries to piece together the nature of what seems to be unveiling itself as a really interesting family crisis and even ghost story.

Because of this, even though Vertigo makes you wait a long time before you understand what it’s really all about, never do you feel like it’s testing your patience or wasting your time. If the second half played out how I had initially thought it might, I would have still likely been invested. But even more importantly, the third act of Vertigo is probably only able to be as disturbing and jarring as it is precisely because it spends all that time building up these characters and their pasts, and the harsh whiplash between where you initially thought they could go and where they end up going makes the characters’ fates hit that much harder. The thrills and suspense are so memorable partially because you go through a lot of the film not even prepared to experience them.

When Vertigo does get into its payoffs and show its cards, you realize that this entire time, the titular vertigo is referring more to the disorientation stemming from a man’s manipulated desires than the literal vertigo that comes from acrophobia. It’s about the dangers of chasing after something that not only isn’t real but does great harm to all parties involved. Though the truth about everything Scottie has seen should be making itself clear as day, his already-fractured psyche is too far gone, having been twisted, tortured, and abused to such a severe degree that his entire world has become unhealthily distorted into what he wants it to be … or, even scarier, what he needs it to be. He can’t tell what’s real anymore, or he at least won’t allow himself to be able to tell. Even when he does, what’s been done to him has brought out an abhorrently controlling and toxically obsessive emotional state that’s taken over everything else about who he is.

The sporadic love affair I mentioned before isn’t just an odd bit of schmaltzy writing, but a hint of the darker nature of things to come. You end up looking back and wondering how much of Scottie’s decisions from earlier came from him fooling himself as much as anything else that was fooling him, giving his more eyebrow-raising, rushed feelings for Madeleine a much more deliberately dark context. Stewart, who I’ve mostly seen play more wholesome, heroic people like in It’s a Wonderful Life, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, or even Rear Window, is entirely unrecognizable near the end of Vertigo. What starts off as an endearing performance transitions into one that’s sad, then questionable, and then slowly works its way up to one of the most terrifying performances in film history, even rivalling that of Anthony Perkins in Hitchcock’s Psycho. All of the performance progresses and flows perfectly into each subsequent step, and the contrast between where the character starts versus where he ends is a big part of what makes him so frightening.

Hitchcock’s directing has a very straightforward, no-nonsense approach like in his other films, without coming across as lacking in style. There aren’t too many complex shots or flashy camera tricks, and even the famous dolly zoom that he practically trademarks with this film is pretty downplayed, only appearing a few times. But he puts you right up close and personal with the characters and their history without ever getting distracted from them, selling you on the faux mystery movie that is the first half and the straight-up psychological thriller that is the second half. That’s not to say that Vertigo doesn’t contain any memorable imagery. Scottie has a dream sequence at one point, and though its simple flashing of color filters and use green screen look dated now, it hypnotically transports you to a disorienting, trippy version of his past experiences and current emotional state, setting you up for the terrors to come. The use of green light as a backdrop to a few scenes adds an almost alien look to events that are already unnerving on their own, and the use of darkness, shadows, and close, imposing angles in the film’s final sequence really contribute to its heart-pounding unpleasantness.

When I first saw Vertigo, I knew very little about it outside of the initial setup, and I was absolutely blown away by how it plants its seeds so perfectly and lets them grow and fester into something so dark and disturbing that it remains vividly in my head long after it’s over. It may take a while to work up to its thriller elements, but it 100% earns its right to be called a thriller, and one of the best, most understated, and ingenious of all time at that. If you haven’t seen Vertigo yet, I highly recommend going in as blind as possible so that it can sneak up on you the same way it did for me and the millions of others who love it. When many critics and scholars declare this Hitchcock’s best film in an already-iconic lineup, it’s pretty easy for me to see why.

Vertigo is now available to watch on digital and on demand.

loudandclearreviews.com

loudandclearreviews.comLoud and Clear Reviews has an affiliate partnership with Apple, so we receive a share of the revenue from your purchase or streaming of the films when you click on the button on this page. This won’t affect how much you pay for them and helps us keep the site free for everyone.