Todd Haynes’ Velvet Goldmine is a cosmically beguiling gem that acts as a tableau on queer identity and repression within the Glam Rock era.

Todd Haynes’ roaring and vivacious Glam Rock drama Velvet Goldmine begins with a phrase: “although what you are about to see is a work of fiction, it should nevertheless be played at maximum volume”. This, in succinct fashion, sums up Velvet Goldmine. It is a pseudo-biopic, an abridged telling of queerness and Glam Rock; an era of liberation and repression as shown through a bombastic and exuberant queer lens.

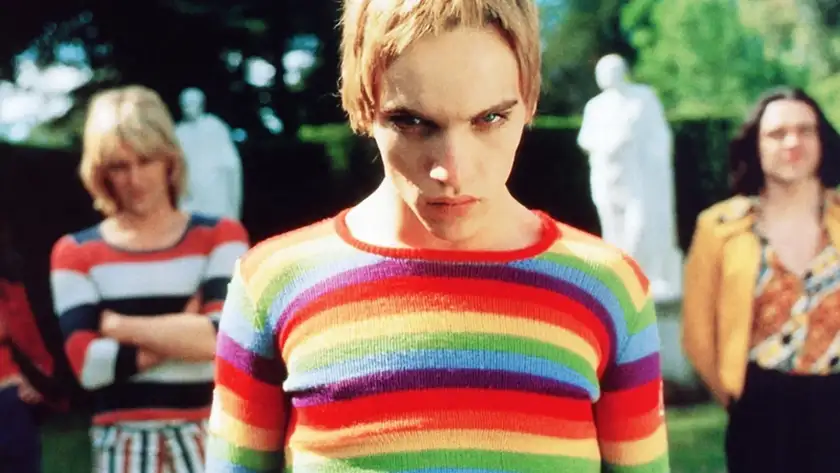

A spaceship opens Velvet Goldmine. The extraterrestrial vehicle flys over a Belfast sky in (1854) to drop off noted Irish poet Oscar Wilde as a baby in Belfast, an emerald pin fastened to the baby’s blanket. Flash forward one hundred years and a bullied and bruised child finds the pin amongst the dirt of London. That child would grow up to become Jack Fairy, a gender-bending rock icon who swaggers across the screen in glamorous make-up and a stylish panache of non-conformity. The proclaimed ‘shipwreck of the streets’ Jack (Micko Westmoreland) would, in turn, inspire a young Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) to become a musician that is as sexually free as Jack. Velvet Goldmine collates the lives of Brian, Jack and fellow rocker Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor) as a series of non-linear vignettes on their lives, shown through flashbacks during the investigative journalism of Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale).

His investigation delves into Brian Slade and his on-stage persona Maxwell Demon, a rock star who had faked his own assassination as a PR stunt ten years prior and promptly lost his crown as one of the biggest names in music. Throughout this investigation, Arthur speaks to various people that were involved with Brian’s rise and fall, including polyamorous wife Mandy (Toni Collette), former tour manager Cecil (Michael Feast) and ex-lover and musical collaborator Wild. But Stuart’s own sexual traumas bleed through throughout his investigation, which is where Haynes speaks on the sexual oppression put towards the queer community, as Arthur is shown to be forced out of his home after his family catch him masturbating to a Brian Slade newspaper.

The Glam Rock era was a time period in the 1970s where the supposed free love of the 60s hippie generation had evolved into something that felt the need to be defined. It resulted in a political backlash that Haynes uses to backdrop Velvet Goldmine’s queer discussion. As queerness, especially bisexuality, became more recognised, it was juxtaposed as something trendy, where even Curt Wild, the provocative gay frontman for fictional punk band The Rats, would chastise people under the impression their queerness was performative.

This plays into Haynes’ Oscar Wilde framing device. The infamously flamboyant poet was imprisoned for his homosexuality, and it’s his famous work “The Picture of Dorian Gray” that is impressed upon the seams of Haynes tapestry of queerness. The novel that was once deemed immoral by Wilde’s contemporary critics plays as parable to the journey Brian goes on; knowing that his beauty will fade, his life instead being played out under the guise of Maxwell Demon and the hedonistic lifestyle that he lives will never bear the fruit of discontent.

Wilde was also known for his wit, and the script written by Haynes sparkles slickly, unfurling in a shower of debauchery, snark and glitter. That Wilde, and Jack Fairy through the osmosis of the emerald pin, are implied to be aliens latches on to the themes of the film, specifically alienation amongst societal peers. Even the Maxwell Demon track “Hot One” features the line “my starship doesn’t want me”. That they are or aren’t aliens is trivial, because Haynes is cleverly invoking the semiotics of David Bowie – or to be more direct, Ziggy Stardust.

Infamously, the rock juggernaut that was Bowie rejected being involved in Velvet Goldmine, but that never stopped Haynes from inviting audiences into seeing Brian Slade as a David Bowie surrogate, with the Maxwell Demon persona a surrogate for Bowie’s own alter-ego Ziggy Stardust. Bowie’s presence is felt in the very lining of the film; the title is that of a Bowie track itself, “Velvet Goldmine”, which was a B-Side on his album “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars”. Haynes also reveals Brian Slade as a fake name, much like David Bowie is having been born as David Jones. It’s all a masquerade, with queer identity on fanciful show: “music is a mask we wear,” the film’s queer characters state.

Haynes is not only using Bowie for semiotic value, but rock artists like Iggy Pop and Kurt Cobain. Ewen McGregor’s Curt Wild acts as a hybrid of their respective acts. Iggy, in his leather trousers and political provocations and in Cobain’s dirty blonde locks. The film weaponises the historical fact of Cobain’s early demise at age 27, too, in that the blend of fact and fiction within the film leaves the audience unsure of which factual facets will be utiliised. This is also shown through versions of Glam Rock songs like The Stooges’ “TV Eye” being covered by the cast, while having them perform original songs like “Hot One”, creating this swirl of fiction amongst historical fact that contributes to the dream-like vibe of the film.

Haynes even touches upon the subcultures of Mods and Rockers within this rich textual film, in how the use of Mod clothes – normally that of suits pressed prim and proper – are a constriction and how becoming a rocker helps break free from that heteronormative conformity. The film presents Brian as a Mod firstly, before becoming a glam rock icon once he discards the bindings of tailored threads that represent conformity. This conformity isn’t solely with Mod clothing as Arthur’s sexual repression also occurs while in the more bohemian dressings of the 1980s. An early line of his, when discussing his former youth as a proud glam rocker, speaks on how money and trying to have a serious life had made him forget what once brought him joy. Haynes is showcasing the repression of queerness within society, about how a culture is excluded if it doesn’t fit in. But Velvet Goldmine is a film that does away with binaries, obscuring these restrictive ideas in a puff of dry ice.

The internal chaos of bisexuality is captured by Haynes both in the kinetic editing and a shooting style consisting of crash zooms. The film is eager to flick through time, Arthur’s trauma spliced in like intrusive thoughts demanding attention. These traumatic memories flitter to the surface throughout the investigation, but none more tangibly evocative than when a teenage Arthur, in a moment of excited fervour, leaps up and shouts “that’s me” in relation to Brian Slade speaking about bisexuality on a TV screen. But that ecstasy is short lived, with Haynes reminding audiences of the derision felt by queer people with a sharp cut to parental disapproval and an aching reminder of the comedown that occurs after experiencing euphoria on sexual identity.

Velvet Goldmine is a film so vastly rich in subtext and intertextual ideas about repression, queerness and the alienation felt amongst queer folk that it transcends what might be perceived as normative film values. A titillating dreamscape of a film that is presented as outrageous and lavish, having the same unbridled flamboyance as the people being portrayed.

Velvet Goldmine is now available to watch on digital and on demand.

Loud and Clear Reviews has an affiliate partnership with Apple, so we receive a share of the revenue from your purchase or streaming of the films when you click on the button on this page. This won’t affect how much you pay for them and helps us keep the site free for everyone.