The Boy and the Heron lets the worldbuilding distract too much from the story, leaving most of Hayao Miyazaki’s magic to go stale.

It’s a huge honor to say that I’m once again going to be covering the Toronto International Film Festival! There’s a lot on offer over the next week, including many movies that I’m really looking forward to seeing and reviewing … but after sharing my thoughts on The Boy and the Heron, I really hope I’m not blacklisted into never being accepted back again. My relationship with renowned anime filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s work is … I don’t want to say love-hate, but rather love-frustration. For every film of his I’ve seen that I find wonderfully animated, moving, and all around excellent, there’s another one that doesn’t quite do it for me. The trend I’ve seen with him is that he seems to let his vivid visuals and worlds drive his story and characters instead of the other way around. That’s not my preferred method of storytelling, but if it can yield a great experience then that’s ultimately what matters most to me.

The Boy and the Heron is supposedly Miyazaki’s final film, although we live in a time where I won’t believe someone in entertainment is retired until they’re dead and buried … and even that’s starting to become questionable. Regardless, I would love absolutely nothing more than to sit here and praise this beloved director’s supposed swan song to the moon and back, boast about how I got to see an excellent film before most other Americans, and hype it up for the general public … but instead, I’m very sad to say that I’m the odd one out who didn’t enjoy the film almost at all.

The story is set during World War II where Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki) is a boy who loses his mother in a fire. He and his father (Takuya Kimura) move to the countryside with his father’s new love interest Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura). Mahito is frequently watched and belittled by a talking grey heron (Masaki Suda), who eventually leads him to a mysterious tower with the promise of seeing his mother again. Mahito enters the tower, and … that’s where I’m at a loss, even after seeing the film.

I’m going to be very upfront, which will either garner some respect or lose you entirely: I don’t get this movie. I don’t get how its world works, why characters make certain choices, or what the film is ultimately even going for. I was trying to get a grasp on some basic idea, but every time I felt like I was getting close, a new development just made the situation even more confusing. Like I said, Miyazaki usually has the visuals driving the story, but he’s at his best when that method results in a coherent story being told. In The Boy and the Heron, various subplots pop up in seemingly endless supply with no rhyme or reason that I could find.

There’s meticulously slow pacing and light plot to immerse viewers in a world, and then there’s meandering around and going off tangents that make no sense and ultimately don’t amount to anything. So much of The Boy and the Heron feels like it’s just making up its story as it goes along, as if Miyazaki had a ton of images lying around and wanted to work all of them in. But, like several of his films in my eyes, that comes at the cost of pure character.

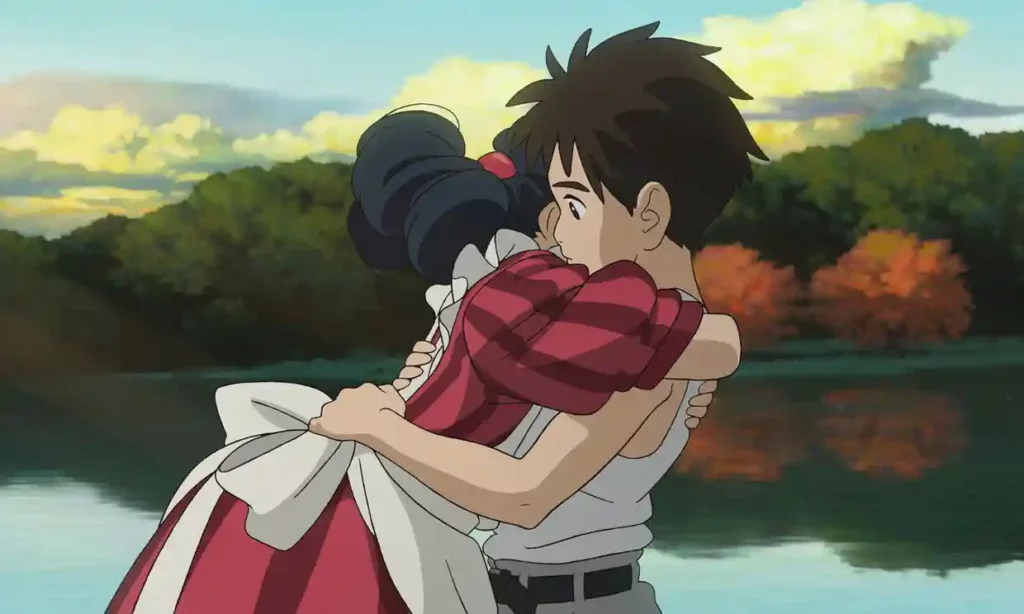

At one point earlier on, Mahito discovers a book with a message from his deceased mother inside, but we never learn what it actually says. The scene just skips to him in tears after reading it. Near the end, there’s a parting scene between two characters that should have absolutely shattered me. But it’s in the middle of a bigger, bombastic scene and just cheerily comes and goes with no sense of emotional comprehension or weight. The heron’s motivation flips on a dime, as does the way Mahito regards him. Certain characters are shown at different ages, but I don’t know if it’s them from the past or some alternate version of them because their actions in other scenes don’t line up with either explanation.

As far as I can tell, very little about the fantasy world actually feeds into what our central characters have been going through in “reality.” Sometimes I see it, but the connection is so loose that it strikes me as hollow. The level of detail is so high that I’m sure there was a lot of thought that went into the worldbuilding here, but that thought didn’t come across for me. You could quote Tenet and say, “Don’t try to understand it; feel it,” a sentiment I usually agree with. But in this case, not only does understanding the world feel imperative to connecting with it, but the world even on a surface level is just … serviceable.

Sure, there are giant parakeet soldiers and little marshmallow spirits roaming around, and that’s all fine and good. What else would you expect from Miyazaki? But that’s kind of the problem: I’m expecting it. After seeing so many of Miyazaki’s movies, I’ve grown a bit numb to his specific brand of creativity. I just feel like I’ve seen this type of world with these types of creatures in other films of his already, even more so because I found no discernible meaning behind them this time.

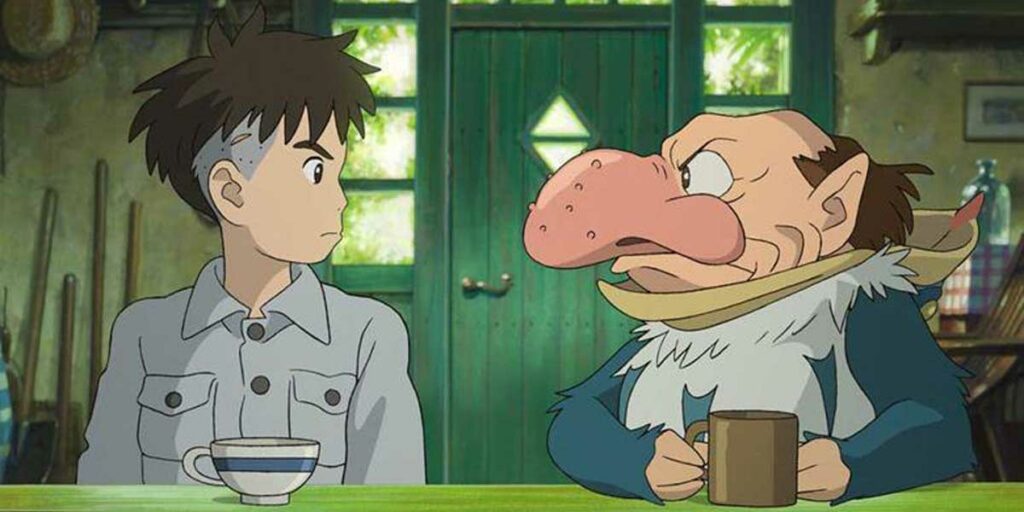

A lot of characters are also flat-out unpleasant to look at, in ways that I think are only sometimes intentional. (Seriously, am I the only one who thinks all of Miyazaki’s elderly characters are ugly as sin?) I can’t tell how much of the imagery is meant to be darkly humorous, but some of it, like a whole bit of cutting open a giant fish and seeing its guts come gushing out, just feels pointlessly grotesque. The movements are animated perfectly, and when Miyazaki wants to build suspense to some big reveal or slam you with a grand, intense moment, he still knows how to put you on edge. In isolation, most of the scenes in The Boy and the Heron are more than fine. I just really don’t like how all the pieces come together. Oh, and there are several shots of white, gooey bird crap. I don’t like that either.

I need to reemphasize what I said earlier: I acknowledge that I didn’t understand this movie. Which means I’m not willing to write it off as definitive nonsense. There could be a whole method to the madness that I’m just not seeing, and I’m sure tons of other critics and fans will be writing up deep, well thought out analyses about the film’s many layers and interpretations. But for me, the experience of watching it the first time wasn’t charming, emotional, or even creative enough to make me want to see it again. I don’t need to be spoon fed, but I at least want the meal to taste good.

What I’ve said here may get a few people to belittle me much like how the heron belittles our protagonist. Listen, if you’re in the overwhelming majority that adores this movie and feels that Miyazaki magic, know that I am deeply, deeply envious of you, to the point where I’m having that oh-so-dreaded feeling that I’m objectively missing so much here. But I can only go off of my own experiences and takeaways, all of which had me feeling nothing but painful frustration when I was finished with The Boy and the Heron. If this is truly Miyazaki’s last film, then I’m glad he went out on what most people consider a high note. The man’s accomplished so much in his life that most of us could only dream of. Sadly, though, that doesn’t always mean I admire the work itself.

The Boy and the Heron premiered at TIFF 2023 in September and will be released in US theaters nationwide and IMAX on December 8, 2023, and in UK cinemas on December 26.