Ronnie’s is a poignant love letter to one of London’s great musical institutions, and to the man behind it.

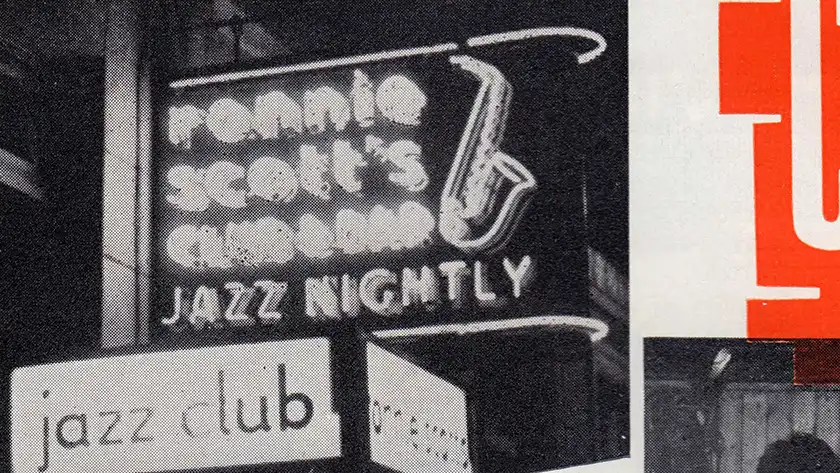

There’s a deep romanticism behind the idea of a jazz club. It has long stood as the epitome of a certain informal, effortless kind of class: small rooms, low lighting, stiff drinks, and above all else the work of performers at the very top of their craft. Ronnie Scott was clearly enraptured by this on his trips to New York as a youngster, and it was this excitement to which the foundation of Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club is credited, a joint venture between Scott and his bandmate Pete King. In the six decades since its formation, it has become part of the furniture in Soho, and a vital item on any aspiring musician’s bucket list.

Ronnie’s is, first and foremost, a tribute. Director Oliver Murray (The Quiet One) sets out to celebrate what the club was founded to do: provide a space for the great musicians of the era to ply their trade, and to embrace true genius in a way few other places do. Murray is adept at drawing an audience into the space he creates, and from the second that hushed chatter and clinking glasses explode into an Oscar Peterson piano onslaught, we do not watch, but absorb. The music is easy to celebrate when the calibre is so immediately obvious – Ella Fitzgerald, Sonny Rollins, Chet Baker and Nina Simone, to give just a small sample. You can feel each performance leaving an indelible mark on the building itself, and with each piece of footage the legend of the institution tangibly swells.

Scott himself must, of course, play a huge part in this story, too, and it is through his life that the film finds its pathos: his origins as a Jewish boy from East London during the Second World War, his early career in music, to his life as a reluctant master of ceremonies at his namesake club and the manic depression that overshadowed it. The story is related poignantly by Scott’s wives and children, and Murray’s direction is skilful enough to interlace the story of a man’s life with the music that dominated it, and through this the performances are amplified and given life far outstripping the grainy recordings.

It is, therefore, a touch bittersweet as the film turns its attention to the future of the club, as the hope that lights its ending has been shattered by the events between the film’s creation and release. Now, more than ever, the club feels like a distant concept, an aspiration rather than a reality, and through shots of empty seats and stages we are reminded of the grim future for many of the spaces for which a thousand stories like this exist. Finance has never been the club’s forte; a magnum of champagne, as the club’s current manager Simon Cooke cheerfully relates, was gifted by a local gangster on the club’s opening with the instruction to open it as soon as Ronnie was out of debt. It is, of course, still unopened.

But Ronnie’s refuses to become too bogged down in the realities that may come with the business. It makes its choice early, not to tell the story as pragmatically as it can, but to elevate the mysticism that must come with an institution of this kind. As related by Mel Brooks, the film speaks in “the kind of unconscious poetry that only good music can speak”, and through this music a story more powerful than anything merely factual reveals itself. Ronnie’s is, undoubtedly, a creation borne from love; as we enter a world where these institutions seem further away than ever, where the buzz of an anxiously excited crowd feels distantly nostalgic and dearly missed, this documentary is soul-satisfying in a truly necessary way.

Ronnie’s is now available to watch on digital and on demand. Read our reviews of Blue Giant and Chicago!