Parallel Mothers doesn’t quite scale the heights of Pedro Almodóvar ’s best work, but a phenomenal Penélope Cruz makes it worth a watch regardless.

There are a select few filmmakers whose every new release is a “must-see” cinematic event. Pop art auteurs like Steven Spielberg and Christopher Nolan certainly fall into this category (and, after the critical and commercial success of Dune, Denis Villeneuve is also well on his way to being accepted into this club), but there are some icons on the indie circuit as well, such as Wes Anderson (whose own The French Dispatch also saw a release this past weekend), Quentin Tarantino, and Parallel Mothers’ own Pedro Almodóvar. Almodóvar’s signature style of sensual cinema has been captivating cinephiles for over three decades, with his soapy but still satisfyingly sensitive storytelling always assuring audiences that they’re in for an entirely original and overwhelmingly emotional moviegoing experience – and that’s why they keep coming back for more.

With the Oscar winner’s prior film, 2019’s Pain and Glory, earning profusive praise and plaudits upon its arrival on the awards circuit two years ago (including Academy Award nominations for Best International Feature Film and for star Antonio Banderas in Best Actor), it stands to reason that expectations for his follow-up feature would be even higher – if his reputation alone didn’t already send them into the stratosphere. But, although Parallel Mothers may not take the title for Almodóvar’s “best work ever,” it’s still a mighty fine addition to his illustrious filmography, anchored by an undeniably awards worthy turn by the phenomenal Penélope Cruz in the lead role.

We begin the perplexing parable of Parallel Mothers by following Janis (Cruz, of Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides), a prosperous photographer who is in the throes of an affair with an alluring client and forensic anthropologist named Arturo (Israel Elejalde, of Love Above All Things and Magical Girl). Ultimately, this passionate fling results in a pregnancy, but while Arturo – who is married – urges Janis to not have the baby, she feels connected to the child and wishes to keep it, especially as the daughter of a single mother who was also the daughter of a single mother. It runs in the family, she says.

Months later, just hours before going into labor, Janis bonds with her much younger maternity ward roommate Ana (newcomer Milena Smit), a woman who is also alone, merely escorted by her absent-minded mother. Both give birth to baby girls, and, on account of their instant attachment to one another, vow to stay in touch. However, this relationship proves more meaningful to both mother than either could have ever initially imagined, as their lives become entwined beyond belief as a result of one fateful occurrence that took place on the day of their daughters’ births – an occurrence that will impact their identities for years to come.

To spoil any of the scintillating twists and turns of Almodóvar’s telenovela-esque saga would be to unforgivably undercut the author’s absurdist (and yet oh so arresting) artistry, so that’s as much information as you’re getting – and truly, it’s all you need, as, within mere moments, the control Almodóvar exhibits over this chaotic chronicle proves too compelling to resist, and you’ll be willing to follow him wherever this torrid tale takes you. As is to be expected with Almodóvar, the writer-director is able to infuse even the most preposterous premise with genuine pathos, so, even when Parallel Mothers feels like it may be wading into melodramatic waters, he anchors this odyssey in authenticity and subverts our expectations by sincerely engaging with his character’s emotions instead of simply relying on his plot beats’ shock value to ignite interest in the audience.

Additionally, while Parallel Mothers starts as a seemingly straightforward study of the struggles of motherhood (and particularly single motherhood) it slowly morphs into a broader analysis of how we must make peace with our past in order to find a better future – a theme Almodóvar explores with both Janis and Ana. Each has specific trauma they have to tackle on their own, with Janis recruiting Arturo to assist her in the excavation of a mass grave in her hometown holding her great grandfather who was murdered in the Spanish Civil War and left behind on a battlefield and Ana having to confront the hurt associated with the assault that initially led to her pregnancy (to say nothing of their additional struggles that arise).

And yet, as these two travel parallel paths to emotional and existential recovery, they find that there’s no one else who understands these endeavors better than each other. This is especially true as riveting revelations tie their troubles together even further, and thankfully, Almodóvar rejects a simple telling of this story by continually throwing curveballs at the audience and adding complexities to Janis and Ana’s relationship. His attempts to make a grander sociopolitical statement about Spain’s failure to reconcile with its own painful past (in regards to the subplot about Janis’ great grandfather who fought and died in the Spanish Civil War) don’t integrate as well as they could with the investigation of intricacy Janis and Ana’s interpersonal reliance on one another, but it’s an admirable addition to the narrative nonetheless, and Almodóvar’s passion is palpable.

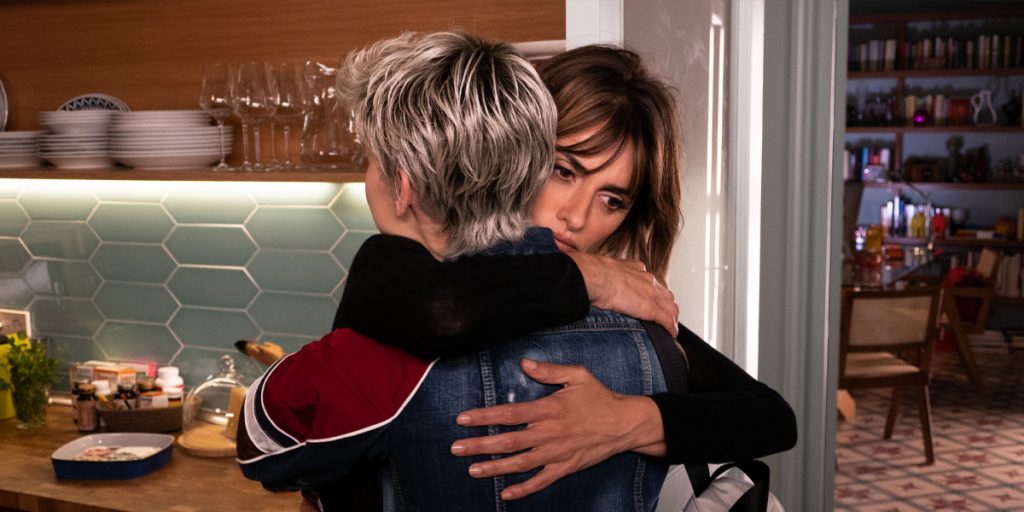

Even when the story starts to feel a bit too crowded with all of Almodóvar’s ideas jockeying for space on the screen, Cruz gloriously keeps things grounded in a performance that may very well be her best since 2008’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona – for which she won her Oscar. Cruz is tasked with exploring the entirety of the range of human emotion in this role – enduring some of the most harrowing hardships a woman and a mother could ever think to face – and she never falters, doing so without resorting to tawdry theatrics or excessive exaggeration. Even when Janis is censoring herself from speaking on a searing secret, Cruz keeps her cool, making her agony apparent but never drawing needless attention to herself. It’s magnificently mannered acting that deserves all the accolades its received thus far – and all that are yet to come. Matching Cruz’s impeccable craft is the stunning Milena Smit, who balances Ana’s youthful and naïve innocence with her incredible intellect, allowing her to relate with Janis on certain concerns but draw a contrast between their characters when we’re reminded of their differences in age and experience – and what one has encountered (politically or socially) while the other hasn’t.

All of the cogs in the movie’s machine eventually collide and bring Parallel Mothers to a rewarding and resonant resolution, making it easier to forgive any minor faults with the screenplay’s juggling of its surplus of subplots and story threads earlier on. Though the film is smaller in scale and scope than some of Almodóvar’s most major works, it’s a marvelously moving ode to mothers and motherhood, aided by truly astounding acting from the always-perfect Penélope Cruz and her sterling scene partner Milena Smit. And, when Almodóvar leaves audiences with a final scene as striking as the one here, it’s impossible for his ideas to not linger in your mind and make you re-evaluate all that you’ve previously perceived during the days and weeks that follow – the true achievement of an accomplished artist.

Parallel Mothers will be released by Sony Pictures Classics in US theaters on December 24, 2021, and by Pathé in UK cinemas from January 28, 2022.

loudandclearreviews.com

loudandclearreviews.com