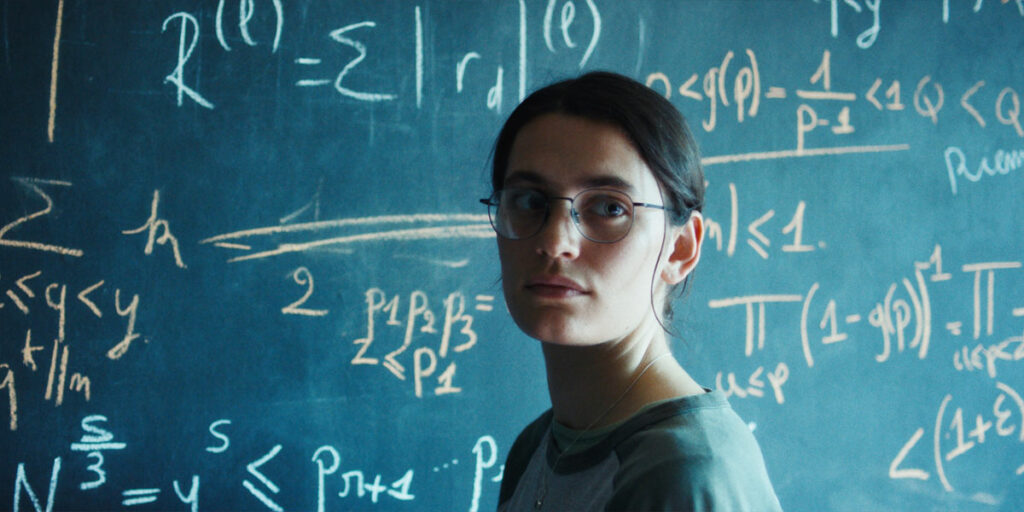

Even if one-half of Marguerite’s Theorem doesn’t end up working, Ella Rumpf grabs your attention.

Mathematics is the language of science, although it is in more written form rather than a spoken one. Galileo Galilei, the Italian astronomer and physicist, said that mathematics was the language in which God had written the universe. What he meant by this quote is how fundamental math is to our very existence. It is more relevant today than before, as it is crucial to our modern life covered in daily technological advancements, with artificial intelligence being the latest one to haunt us. For the titular character in French-Swedish director Anna Novion’s third feature film, Marguerite’s Theorem, this takes a far more literal turn, as all she sees are numbers and equations in every possible encounter, activity, and conversation.

Marguerite (played by Ella Rumpf, who’s mostly known for her role in Julia Ducournau’s Raw) is a brilliant student in mathematics at the prestigious Ecole Normale Supérieure. She eats and breathes numerous equations. And she needs to do so in order to climb the ladder of the ultra-competitive field, where everyone is a target – they all want to belong to the elite group of geniuses that changed the world. Mathematics is Marguerite’s only interest. She enjoys a walk around the university grounds because it makes her think; Marguerite takes those moments of silence to continue to come up with solutions to her studies. Her future seems certain: becoming a professor alongside her mentor, Lauren Werner (Jean-Pierre Darroussin).

Werner believes that his talents in the field have never been appreciated by his peers or the public: he’s resentful in every single matter, eaten alive by his own frustrations. Even though his students and mentees hold him in high regard, Werner still aches for the day he gets to prove everyone wrong. While Marguerite loves working with him, viewing him as a protector, Werner’s holding her down and not fulfilling her potential. From Marguerite’s point of view, their relationship involves feelings, which Werner doesn’t want because, by his beliefs, mathematics and emotions shouldn’t be aligned with one another. It is like a one-sided father-daughter relationship because Werner doesn’t want to play that role. Hence, when a single mistake breaks all of Marguerite’s certainties and foundation while defending her thesis, Werner doesn’t console her.

All her chips are down, so Marguerite decides to quit everything she has loved and start again. However, mathematics is everywhere, and she begins to figure out the mistakes in her thesis while embracing a more mundane and vivid life – a game of mahjong with her tenant’s comrades paving the way for her discoveries. Before watching the film, I thought this was going to be more like Ron Howard’s Best Picture-winning film, A Beautiful Mind. And although there are certain moments in which it calls back to said film, Anna Novion takes a different approach, one that is both charming and filled with genre clichés. The director is interested in exploring many things in the titular character’s life that lead to the obvious ending waiting for the viewer with open arms.

The primary aspect of Marguerite that Novion is interested in is why the character hides her emotions. The lack of feelings, deeming them as inherently irrational, contrasts with her determination to find the solutions to her mathematical equations. But, until Marguerite finally expresses herself, she won’t be able to resolve any of her situations. As seen in Raw, Ella Rumpf knows how to act that part, doing a double-sided performance where we see growth in expression once more people knock on her journey’s door. Her roommate Noa (Sonia Bonny) and colleague Lucas (Julien Frison) are way more in touch with life than Marguerite. While they have their moments of frustration in their own situations, you see the two of them having fun.

When you put one of them alongside Marguerite, you see the difference in character and how she grows slowly because of their companionship. The differences are vast from each other, but Marguerite, Lucas, and Noa accept each other for who they are. This sets up some material worthy of building a throwback romantic comedy around. For me, the coming-of-age love story elements are the most interesting part of Marguerite’s Theorem, more so than the mathematics being involved, even if it is still a story we have seen plenty of times. You see most of Novion’s struggles in the intertwining between the two themes (romance and mathematics) and the titular character’s development throughout the picture. The former doesn’t have to do with the blatant ending to this story; the main reason this intersection doesn’t find its footing is because of the mishandling of Marguerite’s passion and the relationship with her mentor.

This part of the story isn’t developed to its full potential. I wasn’t wholly invested in Werner and Marguerite’s fracture because we never got a reason to do so. Novion, alongside her team of writers, doesn’t give us enough backstory to understand his pain or frustrations fully. Sure, this is Marguerite’s journey. But it feels necessary to explore the culprit of her initial decision to leave. That’s why one half of the film ends up working – the part where Marguerite finally confronts her feelings – and the other one doesn’t. Marguerite’s Theorem may not demonstrate how mathematics can be cinematic, but at least Ella Rumpf makes the film digestible.

Marguerite’s Theorem premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 22, 2023. Read our list of 20 films to watch at the Festival de Cannes and check out our other reviews.