In Glass, Shyamalan subverts superhero conventions through its character dynamics, but ultimately ends with love for comic books.

This article contains spoilers for M. Night Shyamalan’s Glass (2019).

Nowadays, superheroes have taken over the media like a swarm of locusts. You can’t go by a few weeks without some new movie or TV show or holiday special hitting the news about some new costumed character. Naturally, this has also invited many different ways of telling a superhero story. And in 2019, we had another director throw in their take at telling a new tale of heroes and villains through the movie Glass.

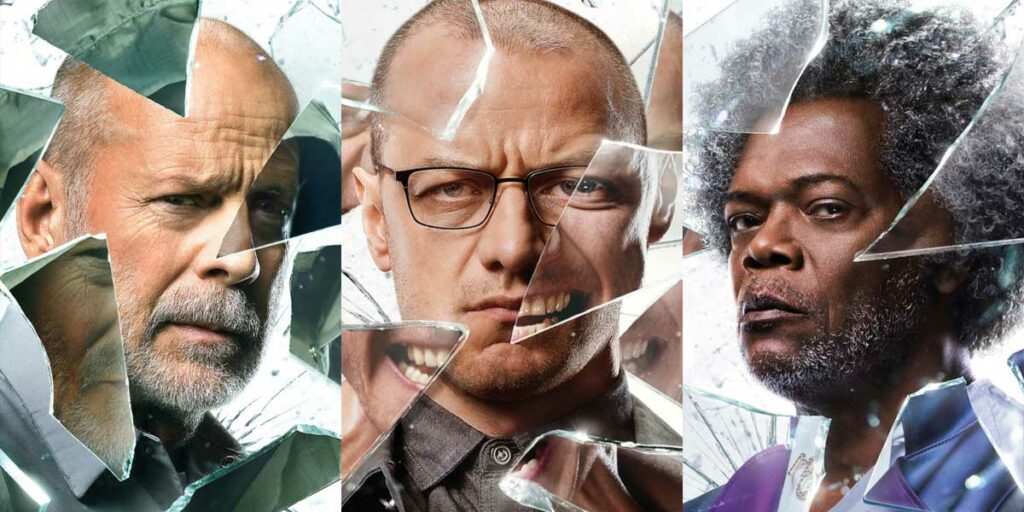

Glass is the conclusion to M. Night Shyamalan’s superhero trilogy, which began with Unbreakable (2000) and Split (2016). The film follows three individuals, each gifted with extraordinary abilities. David Dunn/The Overseer (Bruce Willis) was the protagonist of Unbreakable, and his superpower is, fittingly enough, that he has unbreakable skin. Kevin Wendell Crumb/The Horde (James McAvoy) was the antagonist of Split and is a man with 24 personalities, one of which possesses animalistic speed and strength. Elijah Price/Mr. Glass (Samuel L. Jackson) was the secret antagonist of Unbreakable, whose bones are as brittle as glass. One mishap finds them locked in the same mental institution under the watch of Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson), who tries to convince them that their powers are nothing more than a figment of their imagination.

One needn’t look far to see why Shyamalan is such a controversial director. He has some films that made a permanent mark in the industry, such as The Sixth Sense. But then, other films of his also made a permanent mark – or more accurately, blemish – such as Avatar: The Last Airbender or After Earth. But I was fairly optimistic about Glass leading up to its release, mainly because I was already invested in the previous installments. Unbreakable was a dark reflection of the drama of a superhero, and Split was an intense psycho thriller that made me love James McAvoy twenty-four times as much. And with those two movies having garnered pretty positive receptions, I thought things were looking bright.

However, it seems that Glass has split the seemingly unbreakable streak Shyamalan had going with this trilogy. People seem to be at odds as to whether the movie is Shyamalan going too far with his delusions or a brilliant realization of his genius. In my case, I have to agree with the latter. Of course, the movie isn’t devoid of issues. The dialogue still feels rather wooden from time to time, and some of the actors don’t shine as much as they could have; Spencer Treak Clark as Joseph Dunn is perhaps the closest impression of The Happening’s Mark Wahlberg as we will get in this movie, looking like a cross between a deer in headlights and a MACY’s mannequin.

But overall, I find this a fascinating movie, mainly because of its approach to superhero stories. It isn’t so much a discussion about superheroes specifically as much as it is about the general concept of comic books and its relationship with reality. In fact, while I think the word “subversion” is often overused in film criticism, this is a movie that truly subverts the notion of superheroes, bringing its elements into the real world, while still embracing them in the end.

GLASS’ SETTING: SUPERHEROES AS DELUSIONS

What immediately stands out about Glass is its unconventional setting. 90% of the film takes place in a psychiatric hospital. Within that place, Shyamalan takes the atmosphere and cranks it up to the max. The into-the-cam shots make it look as if the characters were directly counseling you, and the frequent CCTV POVs enhance the cold and oppressive nature of this place. It is rather different from the more grandiose or humanizing settings for superhero movies we’re used to, such as Batman’s Gotham or Black Panther’s Wakanda.

This overarching mood enhances what may be the most unorthodox and strangest way to approach the concept of superheroes: trying to see if they are bonkers. Here, we have superpowered people being counseled on the possibility that their powers may actually be a delusion. This is something that, despite the long history of superhero movies, has never really been explored before. What makes these people super, other than the belief that they are super?

Of course, the fact that these guys know that they have been bending steel and remaining bulletproof and yet their counseling almost convinces them that their superpowers are delusions may be a tad ludicrous for some, but think about it. They weren’t part of a super-soldier experiment. They can’t sprout claws from their hands. They can’t fly, shoot webs, or blast lightning bolts from their hands. In a way, these are the most “realistic” superheroes you can find: they definitely are abnormal, but they aren’t completely inhuman to the point where you have to accept their superpowers are real.

That is what makes this story work. If someone locked Superman up in a madhouse and attempted to suggest that his powers were a delusion, the mere situation would be a comedy; a few eye lasers later, and you’d have something no doctor can explain. But with David Dunn and The Horde, it’s different. The way their doctor deconstructs their sixth sense (ha) or feats of super strength works because what they did – getting weak in water, figuring out people’s sins, climbing walls or bending steel – seems plausible in the real world as well, under certain circumstances. And the setting of the mental hospital ties into this, because it is full of people whose job is to analyze and break you down.

Yet, just because it seems plausible for their powers to not be real, it doesn’t mean they still aren’t, and that’s ultimately what the film focuses on. Glass’ protagonists have still done extraordinary feats, and their belief in those feats is their true power. In the end, all three of them embrace their “super” alter egos and break out of the hospital. It is superheroism occurring in a place where everything is trying to normalize them, and the movie rejoices in it.

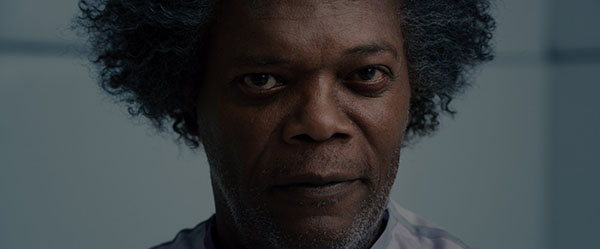

MR. GLASS: ESCAPISM TURNING TO OBSESSION

The aforementioned superheroism versus realism is also what fuels the actions of the film’s titular Mr. Glass. Elijah Price has incredibly brittle bones, and therefore lived a precarious life. Because of this, he turned to fantasy, more specifically comic books, as a means to an escape. Within those worlds, physical conditions like his own wasn’t a disability, but instead a character quirk, something that makes them an important part of the plot. That escapism slowly festered into an obsession, a madness for superheroes and villains to be real, because otherwise he is just a crippled man.

What is interesting is that he isn’t searching for supers because he wants to take over the world or something. No, his overarching goal in life is to simply find them, to prove that they are real. His goal is actually not that villainous – he just wants to see comic books become reality – but he will achieve it by any means, going as far as to cause plane crashes, train accidents, and various other disasters just to find a superpowered being survive it.

That level of determination is chilling, not just because he killed countless innocent lives, but because his motivation stems from feelings of escapism that we as audiences understand very well. We too retreat into outlandish stories to forget our real-life troubles for a moment. It’s why we gladly pay twenty bucks for the next superhero movie.

But when that marvel turns into an obsession that intrudes upon reality, trying to distort it to suit one’s imagination, it creates a character who is terrifying because of his relatability. It is why some people fly into tirades online because their favorite heroes got a bad adaptation, or to prove one comic character is better than the other, until that is all they care about. Mr. Glass is a reminder to keep our passion in check, because love towards comics can sometimes go too far.

DR. STAPLE: THE REJECTION OF COMIC BOOKS

However, Mr. Glass isn’t the film’s only antagonist. During the climax, we see that Dr. Staple is not a regular psychiatrist. Instead, she is revealed to be part of an anti-superhero organization that has lasted over many eras, dedicated to stopping the rise of superpowered beings by any means necessary.

I will be blunt: on my first viewing, my reaction to this twist was akin to how one reacts to a grasshopper in their laundry basket. And even after multiple watches, while it doesn’t break the story overall, I think it could have been handled a bit better. There doesn’t seem to be enough buildup deserving of such a sudden and massive reveal. Sure, we already understood that Staple was trying to erase supers, but I am not sure if it warranted bringing HYDRA into the mix.

But I am willing to overlook it because, thematically, the actual existence of such an organization actually does make sense in the larger narrative. Staple’s organization are a group of people that firmly believe that supers should not exist for the sake of keeping the world safe and normal. It once again approaches the concept of superpowered beings in a realistic context. While some might welcome superheroes, not every super will be a hero, and that danger will always be present. Therefore, there are bound to be those who fear the possible damage superpowers could cause and wish to suppress it.

However, Dr. Staple’s organization serves another purpose other than showing realistic reactions to superpowers. These are people who don’t believe in outlandish tales, and who try to beat them down, erase them from their memories, and commit to reality. In other words, they are the very antagonists of unorthodox imagination, something comic books wholeheartedly embrace.

Comics are filled with exaggerated costumes, bizarre superpowers, and over-the-top aliases. Yet there are people who find this all silly, and this sort of mentality has led to many superhero films taking a darker and grittier approach. Many movies don’t give their characters proper costumes, opting instead for hoodies or body armor you’d typically see in real life. In fact, some of them go as far as to never say the characters’ comic book aliases out loud.

Thus, Dr. Staple and the organization is the result of taking the rejection of comic book fantasy beyond acceptable limits. And by putting them at odds with Mr. Glass, who proudly declares himself through that supervillain name, the movie sets up a battle between fantasy and realism, which all culminates in the climax.

GLASS’ ENDING: FANTASY WINS OVER REALISM

I’ve seen many people criticize the climax to Glass as anticlimactic. And on my first viewing, I was admittedly on board with them as well. Mr. Glass breaks out of the hospital after recruiting The Horde, and promises a big public showdown between Dunn and The Horde in order to show the existence of superpowers to the world. However, the actual fight remains within the hospital grounds, and eventually, Staple’s organization kills both The Horde and Dunn, stopping Mr. Glass’s plan. I couldn’t help but feel deflated at that. However, in the final few minutes of the movie, it is revealed that Mr. Glass never intended for them to go out into public – at least, not physically. Instead, he tinkered with the CCTV footage of their fight so that it gets released onto the internet.

This ending is brilliant because for one, it is cleverly set up, unlike the reveal of Staple’s organization. The film established that Mr. Glass could easily have gotten out of his cell to wander around at night, and also showed him tinkering a bit with the computers. In fact, the method we see a lot of important scenes in this film as, including the final fight, is through the CCTV format. It is such a satisfying twist that works because of how fascinating a character Mr. Glass is that you can’t help but get invested in his victory.

Yet another reason why the ending works is because it is both a reality check and an acceptance of the superhero trope of the big hero vs villain showdown. Of course, David Dunn vs The Horde in front of the world would have been the expected ending, but the twist shows that, in the end, both heroes and villains are people. There’s a limit to what they can – and can’t – know and do. This applies to comics in real life as well. In the end, there is no man of steel who can lift cars or put our fires with his breath, and we have to accept that.

And yet, despite all that, Mr. Glass succeeds, just not in a conventional way. While he ultimately pays for his sins of mass murder through his death, the movie ultimately supports the very core of his actions, that desire to see comic books brought to life. This message ties into the film as a whole here, because it is speaking to every comic book fan or even just subculture fanbases in general. Even if you live in reality, it is okay to love what you love, don’t let anyone else dissuade you from that. Just make sure not to become a Mr. Glass.

GLASS: SHYAMALAN’S DIVISIVE VISION

Ultimately, Glass is something very different in the midst of more conventional superhero movies. It doesn’t adapt any comic book characters, but it’s more of a discussion of those comics, the various reactions to their ludicrousness, and how that has influenced the media over the years. This is also why I feel like this is one of the very few superhero films that actually deserve to be praised for subverting the genre. It makes love to many comic books and, at the same time, it finds a way to analyze them in a way that both supports and subverts the genre.

I can understand why Glass is divisive. Not all elements of the narrative flow quite as smoothly, and some might find its monologues about comic books pretentious. However, I believe it comes from a genuine love of comics from Shyamalan. The film is him expressing that love in his own weird way. But this is the good kind of weird. The kind that you feel when you order some random dish at a Chinese restaurant and get an atomic bomb of different spices in your mouth. Some may dislike it for its overflowing uniqueness, but I ended up quite captivated with it.

Glass is now available to watch on digital and on demand. Read our reviews of M.Night Shyamalan’s Trap, Knock at the Cabin, Old, The Sixth Sense, Signs, The Visit, and The Last Airbender.