One of the defining films of the 1980s, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet is a deranged, terrifying masterwork of exquisite visual prowess and controversial subject matter.

Blue Velvet may be more narratively cohesive and formally linear than Mulholland Drive (2001) or Eraserhead (1977), but it is no less disturbing. Skirting a fine line between fact and fiction whilst still remaining consistently grounded in the gritty realism of a criminal underworld, David Lynch’s fourth feature film is a heady, disconcerting blend of genres, mixing psychological horror, neo-noir and mystery thriller elements; Lynch even finds time to add in melodrama and romance amidst the twisted chaos. The depictions of sexual violence ensured it was a controversial film on its release, and its impact on the legacy of film as a whole cannot be underestimated. From the placement of the audience as a voyeur to the idyllic setting juxtaposed against horrific violence, Blue Velvet is a film which screams with influence.

Blue Velvet opens with an intensely blue shot not of velvet but of a clear sky, instantly conjuring up a perfect picture of suburban bliss: there are the pristine flowerbeds on healthy green lawns; a man on a truck waving and smiling in the sunlight; a lollypop lady helping kids cross the road. But in an instant, this façade is shattered, as a man watering his flowers suffers a stroke. Lynch doubles down on the unease, slowly zooming into the grass, dirt and bugs, with macro shots of scarcely believable intensity. It is here that the hellish dreamscape of Blue Velvet comes into full focus.

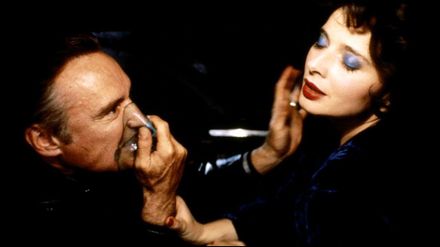

Kyle MacLachlan’s (Dune, Twin Peaks) naïve college student Jeffery Beaumont returns to the sleepy town of Lumberton, North Carolina, after his father’s – that man on the lawn – sudden stroke, with things taking a further turn for the worse when he discovers a severed human ear in a parking lot. Jeffrey’s subsequent journey of intrigue takes him into dangerous situations with drug lord Frank Booth, who is brought to life by a terrifying Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider, Out of the Blue), as well as Dorothy Vallens, a singer controlled by Frank and played by a brilliantly intense and desperate Isabella Rossellini (Death Becomes Her).

What makes Blue Velvet such a memorable experience is its merging of melodrama with surrealism and, perhaps more importantly, how noticeable this is. A film like Parasite (2019) mixes swathes of genre seamlessly, but in Blue Velvet, this combination is defiantly and purposefully alluded to. Lynch and his actors recognise that ramping up this juxtaposition of genres and styles makes the darkest moments that much scarier; scenes of Jeffrey kissing his girlfriend Sandy, played by a radiant Laura Dern (Jurassic Park, Marriage Story), sit uncomfortably alongside the moments of sexual violence. The acting is over-the-top, with emotions exaggerated in synchronisation with Lynch’s pitch-perfect script. Reality is continually distorted within Blue Velvet, with the melodrama heightening the tense fragmentation of suburban utopia.

Blue Velvet also showcases Lynch’s strength at utilising locations – both exterior and interior – for ultimate symbolism. In Dorothy’s flat, where she is raped by Frank whilst he huffs on gas and sobs amidst the violence, the bleak claustrophobia mirrors the restrictions on the singer’s personal life (Frank has abducted her husband and son) as well as her body, which is violated in the room’s very confines. Jeffrey also witnesses this whole encounter; first Lynch frames his face looking out from the relative safety of a wardrobe at the horrific event, before switching our viewpoint to Jeffrey’s, thus making us as complicit as him in this perverted voyeurism. In the mould of Hitchcock, Lynch forces us to look first at the events onscreen, and then inwards at ourselves, asking why we watch films like this. Just like the smog-soaked streets of Victorian Britain in The Elephant Man (1980) or the glitzy but dangerous avenues of tinseltown in Mulholland Drive, Lynch’s use of setting as a means of symbolism in Blue Velvet is provocative, brave and unforgettable.

As the mysteries unravel alongside the romantic subplot of Jeffrey and Sandy, Blue Velvet morphs into a very serious portrait of the deepest, darkest recesses of humanity. Frank’s ultra-villain has no redeeming features, and is a role that makes Hopper’s performance in Out of the Blue (1980) seem tame in comparison, whilst Jeffrey’s ambiguous missteps into the underworld he is becoming swamped in signal the fragility of innocence. Seductive and revolting with mystical, memorable cameos (Dean Stockwell’s performance of Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” is one of the greatest ‘small’ roles ever), Blue Velvet is a seminal piece of cinema, as dangerous and immense in its depth as the blue velvet curtain its title card is placed on. Simultaneously a twisted love story, a neo-noir thriller, a gangster flick and more, Blue Velvet is one of the most deranged exhibitions of the vile, seedy underbelly of American society ever put to screen.

Blue Velvet was released on September 19, 1986, and re-released in 2001 and 2016. The film is now available to watch on digital and on demand.