A sweet reflection on childhood and the perfect example of magical realism, My Neighbour Totoro is a film that will never get old.

After being first released in 1988, My Neighbour Totoro is still one of the most famous, if not the most well-known to the general public overall, films by the legendary director Hayao Miyazaki. Despite not being my favourite Studio Ghibli film – Porco Rosso will always have a special place in my heart – My Neighbour Totoro is particularly fascinating to me because of the widespread cultural impact it still has to this day. Not only is it often featured as one of the best Japanese Animated films of all time, but revisiting it also feels nostalgic and timeless as a film that will never get old.

Set in Japan in the 1950s, My Neighbour Totoro follows Satsuki (Noriko Hidaka), her younger sister Mei (Chika Sakamoto), and their father Tatsuo Kusakabe (Shigesato Itoi), a university professor, as they move to an old house in the countryside at the beginning of the film. Their new home is a lot closer to the hospital where the girls’ mother Yasuko (Sumi Shimamiti) is recovering from an illness that has kept her away from her family for a long time. One day, when Mei is alone, she ventures into the forest that surrounds her new home and befriends a large and friendly spirit that she calls Totoro who seems to only show himself when the girls need help.

The Depiction of Childhood in My Neighbour Totoro

With its protagonists being children, one of the most important themes in My Neighbour Totoro is the exploration of childhood in cinematic terms. In many ways, this film manages to do something that many more recent movies have failed to portray on screen: showing the children as fully-fledged characters with complex emotions and feelings rather than just having them as infantilised additions to the plot. Both Mei and Satsuki are the very heart of the film as everything we see, Totoro first and foremost, is through their eyes and point of view.

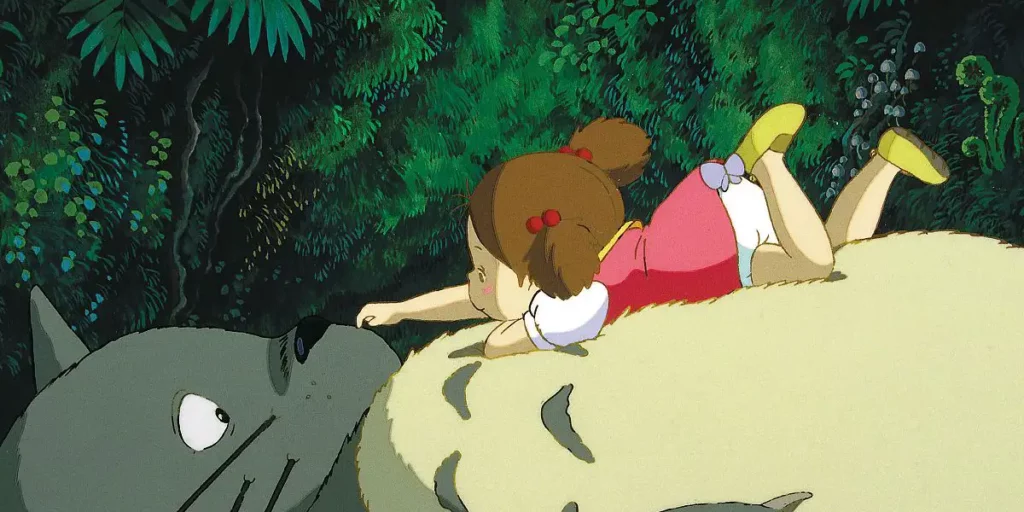

In this sense, My Neighbour Totoro does an excellent job of portraying the childlike wonder that Mei and Satsuki experience when they explore their new home. Visually, this is evident in the portrayal of Totoro whose physical aspect seems to have come straight from a kid’s imagination, as well as in the forest near their house which looks endless and threateningly huge when Mei gets lost in it, but suddenly a lot easier to navigate when the girls are accompanied by their father. Totoro is also only visible to the girls but never to the grown-ups: it is in many ways their special power to cope with the fear of losing their mother as he is always there to look over them in times of trouble.

Magical Realism and Narrative Structure Make My Neighbour Totoro Unique

My Neighbour Totoro is also a masterclass in magical realism, a genre dear to Miyazaki whose films often move between the realms of the fantastical and the mundane life. The entire setting of 1950s Japan is rooted in realism and very accurate to the culture of the time, but the presence of Totoro – and, therefore, the children’s imagination – allows us to open a window to the extraordinary. A big part of the timeless charm of this film resides in this perfect balance that it manages to achieve between the believable aspects of everyday life, with Satsuki going to school or visiting their mother in the hospital, with the magic and wonder of Totoro’s presence.

Its narrative structure is also particularly fascinating, especially to Western audiences who may find it unconventional and unusual. In fact, it does deviate from the classical structure we are used to seeing in this type of children and coming-of-age movies. In western media, this genreusually includes some key pivotal moments such as an inciting incident, a call for adventure for the main character, and an overall resolution of the conflict. My Neighbour Totoro, instead, moves away from the three-act structure and the good-against-evil dichotomy that characterises the majority of Western filmmaking, making its storytelling even more special and fascinating to watch.

With its recent re-release in UK cinemas, My Neighbour Totoro proves that the film will never get old. It is still a timeless classic, and will remain so for the years to come, that modern audiences will also learn how to love – or re-discover, as in my case – on the big screen. It is an ode to children’s incredible imagination and how important these fantastic and imaginary adventures and friends can be in such formative years of their lives, especially when they provide them with a chance of escapism in the face of real-life challenges as those Mei and Satsuki face with their mother’s sickness.

My Neighbour Totoro was re-released in cinemas across the UK and Ireland from August 2, 2024. Read our review of My Neighbour Totoro!