In Violet, Justine Bateman gives a voice to the generations who are fighting silent battles with the voices in their head, highlighting the need for empathy and compassion.

Even though I’ve been living with anxiety for pretty much my entire life, I’ve only started to talk about it fairly recently. I have a very clear memory of the first time I told one of my closest friends about the voice in my head — the constant commentary I’ve been carrying with me ever since I can remember, and the relentless judge that never ceases to remind me that my choices are wrong, that nobody likes me, and that I’m destined to fail. I’m talking about the everpresent companion that makes you cancel commitments, lash out at friends for no reason, spend entire nights worrying about insignificant events from your past, deny yourself everything just to please others, and ultimately wipe out your entire personality out of fear of doing the wrong thing. To those who aren’t acquainted with this specific brand of anxiety, this will probably seem like an exaggeration: after all, how can anyone function if most of their energies are being used to engage in a constant battle within their own heads? But if you’re here because Violet‘s plot sounded appealing to you, you probably know exactly what I’m talking about.

It’s a debilitating internal fight that too many of us are constantly having to deal with, yet it’s also a silent one. We’ve gotten so used to living with intrusive thoughts and images that aren’t our own that, most of the time, even our closest friends aren’t aware of everything that’s been going on on the inside. And so, we hide all our fear, our shame and our helplessness, and deny ourselves the right to be free. We conduct perfectly normal lives and we go through the motions, putting on a public facade that hides our personalities and desires from the rest of the world, and, sometimes, even from our own selves. With at least ten percent of the world’s entire population (and twenty percent of children and adolescents) suffering from mental health issues, it was about time someone like Justine Bateman came along, giving a voice to the fears and anxieties of generations of scared, unhappy people who have gotten too used to suffering quietly and alone.

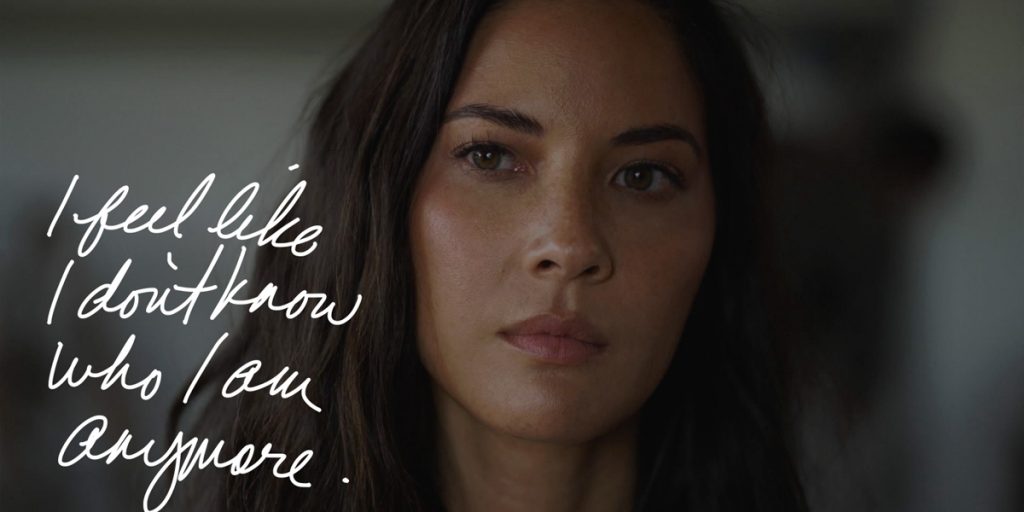

Violet‘s titular character (played by a great Olivia Munn, of The Newsroom and X-Men: Apocalypse) is a 32 year-old film executive, and the “Voice” in her head is as demanding as it is relentless. “Be nice. Don’t be bossy”, it tells her. “Don’t embarrass yourself: people are going to think you’re a loser”. It’s a Voice that never fails to instruct her on what to do and what not to do, how to act, what to tell and what to hide, and how to please others. “If you don’t show [your boyfriend] you’re more relaxed, he’s going to leave you”. As Violet pleasantly interacts with friends, makes informed decisions at work, and shows the world a perfectly normal, self-assured human being, this overbearing, judgemental presence never fails to remind her that she’s “a worthless loser”. Deprived of a voice even in her own thoughts, our protagonist becomes a passenger in her own head, seemingly unaffected by the toxic behaviour she withstands on a daily basis at work while suffering in silence and only barely surviving, beneath the surface.

What’s really impressive about Violet is how easy Bateman makes it for us to feel all the emotions felt by her leading character, and she does so by taking full advantage of the medium. As Violet lives her life perfecting her outer persona while keeping her inner judge at bay, her real self appears in the form of scribbles on the screen that show us just how helpless, torn, unhappy, and afraid she is: this enables the director to show us the fragile balance between the three coexisting sides of her protagonist’s personality — the mask she puts on for the world, the Voice she has no choice but endure, and her silent, authentic self, who just wishes to be free. When it all gets too overwhelming, Violet gives in to panic, and her emotions are effectively shown with a screen that slowly, but methodically, begins to verge towards a very specific shade of red that ultimately takes over, with a humming noise that grows louder and louder until it’s all we can hear. Thanks to the work of cinematographer Mark Williams (Lost in Translation), editor Jay Friedkin (Babe), and sound designer Nathan Ruyle (Searching), Violet gives us a visually and auditorily accurate depiction of its protagonist’s struggles, and makes it easy for us to recognise our own internal battles in it.

Whether or not you are familiar with the events portrayed in the film, there’s no denying that Violet is also an exhausting film, as it should be: it’s no easy feat to live with the voices in our heads, and, as we watch Violet attempt to regain her freedom after discovering that her own Voice has been lying to her her whole life, the film makes it a point of never losing sight of her internal debates. Which is what makes Bateman’s directorial debut so brilliant. It’s by giving us such an accurate insight into Violet’s thoughts that this truly remarkable, at times even therapeautic feature invites us to be compassionate and empathetic to one another, highlighting how hard it can be to live as a prisoner of your own mind. At the same time, I worry that the specificity of its portrayal of mental illness might also make Violet a film that you’ll adore if you can recognise its dynamics, and immediately abandon you don’t. I really hope I’m wrong, as it’s those who belong to the latter category that need to see it the most.

Violet had its World Premiere at SXSW Online on March 18, 2021. The film will open in New York and LA on October 29, and then be released in US theaters on November 5 and on demand on November 9.