With its use of archival material and interviews, Riefenstahl makes us come face to face with Leni Riefenstahl herself.

Director: Andres Veiel

Genre: Documentary

Run Time: 115′

Venice Premiere: August 29, 2024

U.K. Release: May 9, 2025

U.S. Release: TBA

Where to Watch: In UK & Irish cinemas

Most people would have heard of Leni Riefenstahl, the real-life woman who inspired the documentary that takes her name. And if you are not familiar with her, you would probably know Triumph of the Will, one of her most famous – and controversial – films. Whether we like it or not, Riefenstahl’s fame will most likely remain in the years to come. Her films have had a profound impact not only in documentary filmmaking but also in defining Nazi Germany and portraying the regime’s ideals.

Therefore, it does not only seem interesting, but also necessary to have a documentary made about her, especially in today’s political climate.

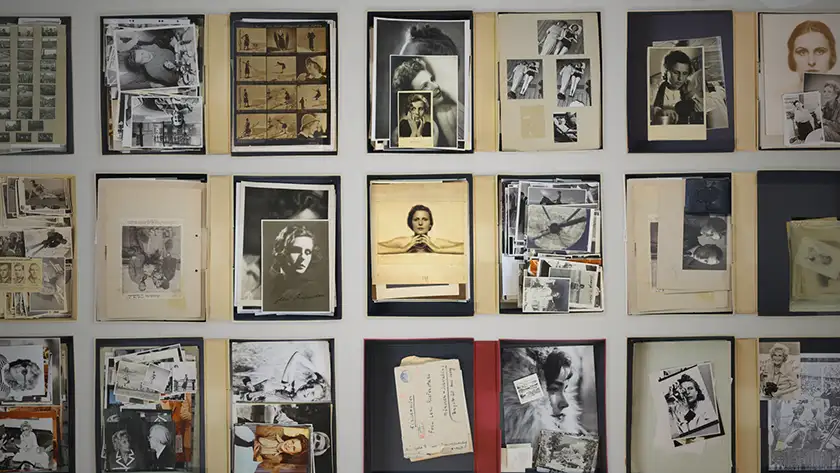

Riefenstahl invites us to take a closer look at one of the most controversial figures of the 20th century: Leni Riefenstahl, a German film director who is best known for producing Nazi propaganda. The documentary uses archival footage, parts of the many interviews she released over the years, as well as private photos and recordings kept by her estate to create an accurate picture of who Riefenstahl was and what her ideas were. Much of the controversy around her is the matter of whether or not she was complicit in the Holocaust: Riefenstahl denied this all her life, as the documentary shows, but was she really kept in the dark about everything that was happening around her?

I liked how the film uses footage from Riefenstahl’s own films. Triumph of the Will (1935) does of course feature multiple times, but Olympia (1938), another one of Riefenstahl’s most famous films, and other lesser-known works, such as The Blue Light (19329, her first film. This allows Riefenstahl to let the films speak for themselves. While Leni herself might try and deny her ideological sympathy to the Nazi ideals after the Second World War, the footage of her films lets the audience make up their own mind on this matter, exposing the numerous contradictions in the narrative she chooses to create for herself.

The value of a documentary like Riefenstahl is undeniable, especially today, when the far right is on the rise across Europe and the United States and people like Riefenstahl, who claim to have only followed orders like anybody else, certainly exist and be very dangerous in the future. However, the structure of the film is not entirely successful and ultimately hurts its pacing. The interviews are not shown chronologically but, instead, constantly jump in time, spanning the many years of Riefenstahl’s life that she essentially lived as a public figure, given the sheer volume of interviews we see and the concerning amount of support she seems to have received from her loyal fans.

The film makes some interesting points but unfortunately fails to see any of them through. Instead, it chooses to include too much. This gives us a very clear idea of both Riefenstahl as a person – she appears resolute and controlling, despite her own description of herself as a naïve young woman who could never stand up to the Nazi regime – and of her unwavering ideas. But at the same time, it misses the much more interesting nuances and discussions that could have been explored in Riefenstahl. For example, Riefenstahl herself touches on the matter of art and politics, claiming that art is entirely separate from politics in one of the interviews that the documentary uses.

In Riefenstahl, this seems only mentioned in passing, and yet this is a key element to understand both the woman herself and the wider context in which she operated. The fact that she described herself – and, therefore, her films – as apolitical is a key element of Riefenstahl’s arguments against the people who accused her of supporting the Nazi regime and, arguably, in her acquittal from such crime after the Second World War. The question of the intersection between arts and politics – and of how the two influence each other – is a complex one and it would probably need its own documentary, but I wish the film had explored it more given how important Riefenstahl and her films are to this debate.

Overall, Riefenstahl definitely feels too long. Its concept and intent become clear within the first half of the documentary, making the second half feel increasingly redundant and uninteresting as the points being raised are constantly the same over and over. However, it is also a necessary documentary that forces us to uncomfortably sit with a much discussed, and arguably much hated, figure that is as essential to the history of cinema as she was detrimental to that of the world, given the significant role she played in creating Nazi propaganda.

Riefenstahl had its World Premiere at the 2024 Venice Film Festival on August 29, 2024 and will be released in UK & Irish cinemas om May 9, 2025. Read our review of Manas!