We interview Nader Saeivar, writer-director of The Witness (Shahed), winner of the Orizzonti Extra Audience Award at the Venice Film Festival.

Nader Saeivar’s The Witness (Shahed) pointedly and powerfully explores one woman’s refusal to be intimidated by a government who consistently covers up the crimes of those loyal to its regime. The film features a formidable performance from Maryam Boubani as Tarlan, a woman from a generation used to protesting for their freedoms, and someone who is not interested in an easy life made possible by bowing to pressure.

After the murder of someone she considered as being ‘like a daughter’, Tarlan faces increased pressure to avoid reporting it to the authorities. When she ignores the plea and does so, she is then intimidated into rescinding the accusation, since the murderer just so happens to be a high-ranking official. It’s a film that sensitively approaches a subject that is not an unusual occurrence within Iran, and Saeivar understands the power of telling such stories poignantly and respectfully.

The Witness is also co-written by Jafar Panahi, another Iranian filmmaker who has faced considerable governmental punishment for his work, and yet continues to produce admirable and acclaimed films. We sat down for an interview with Nader Saeivar to discuss working with the influential filmmaker, as well as Tarlan’s character and the impact of The Witness’ political message.

Nader Saeivar on the women of The Witness

While there are three female characters, you chose to have the oldest be the centre of the film. Why was that?

Nader Saeivar: It’s an intergenerational conflict that started with the Iranian revolution in 1979, when Tarlan’s generation were on the street protesting. This was followed up with the Iran/Iraq war in the 80s, which the government used to suppress the women. That was a very dark period for Iranians when a lot of intellectuals and creatives were killed. Of course there was no social media then, so nobody knew about it, but now that there is, I wanted to show how what we see now on the streets of Iran is not coming out of nowhere. There have already been two generations of women raising their children to find other ways to fight oppression.

The dance sequence at the end is so inspiring and defiant. Was the intention to have it be a liberating experience and for the wind to symbolise the women’s revolution?

N.S.: Yes, that’s well observed. It’s a symbol of the storm that can break out of the women’s movement in Iran at any time. There is also a scene previously, when Tarlan is waiting in the office for her son and the sound from above is explained as ‘maybe the wind’, so you can see what that is and how it is influencing the change.

Although the film is called The Witness, the murder itself is never shown. Was there ever a version of the film where it was ?

N.S.: A very prominent part of Panahi [Jafar Panahi, who co-wrote the film] and I’s filmmaking style is point-of-view, so I don’t like to show scenes out of the point-of-view of the character who is telling the story. If Tarlan had seen it, then yes it would have been included, but it was never in the script.

Is that something you’ve picked up specifically from working with Jafar Panahi?

N.S.: Yes. As well as having 360 degree shots, like at the beginning of the film in the dance studio. And if I forget the rules, and Panahi doesn’t give his ‘okay’ on a shot, we have to do it again. While I’m not as much of a perfectionist, he is my master.

Nader Saeivar on The Witness’ political nature

By including characters like Salar, Tarlan’s son, who are very much a passive character, were you criticising the people who choose to turn from injustices?

Nader Saeivar: He symbolises the people who know they have no chance if they try to fight back, who just put their head down and try to have nothing to do with politics.

Arash T. Riahi [producer and translator]: Most of the time changes in societies happen through minorities. It is not the masses that are out on the street and putting videos on social media. But they spread it around and if they do it enough, then the majority will join them. That’s how change happens.

What can the men of Iran do to help the women who have been brave enough to protest already?

N.S.: The only thing they can do is denounce the crimes of the government, since around 90% are not even known. We need to make the government ashamed in the eyes of the world and keep pressure on them.

A.T.R: Religious entities work on morality, and so if you go for that morality then that is the worst thing for them. If you do that on a global level, that’s where it hurts the most.

And how do you see the movement progressing, going forward?

N.S.: With issues like this, it is often survival of the fittest in that both the government and the people are just trying to survive. It is an ongoing struggle, and there is no clear answer.

A.T.R.: And I’d like to add that there is no dictatorship that lasts forever, the question is will the end of it be a violent revolt or not.

Do you worry about the implications of The Witness and how it will affect you making films in Iran in the future?

N.S.: There are around nine million Iranians living outside of Iran, so their stories can certainly fill the rest of my career. And I do not need to go back to shoot there, as to make films about Iran you do not have to be in Iran. But you never know what will happen. The worst that can happen for Panahi and I is that we will be put in jail for 4-5 months, but we can use that time to write the script. Most of the films coming out of the Iranian underground movement have been written in prison. Even when developing The Witness, Panahi was in jail for some of it and we communicated by phone.

Nader Saeivar on working with Jafar Panahi

How did your collaboration with Jafar Panahi come about?

Nader Saeivar: We actually met around 2016 or 2017, when Panahi was under house arrest and couldn’t leave Iran. He flew to Tabriz and we met for a coffee. He told me about a film he was planning and together we worked on the script [which became 3 Faces, the winner of ‘Best Screenplay’ at Cannes in 2018]. Since then we have become friends and exchanged a lot of ideas. He was at the shoot for this film nearly every day and then we’d edit together at night. It’s all very collaborative. We’re working on a film currently and constantly call each other to chat.

Does Panahi reach out to a lot of Iranian filmmakers?

N.S.: It’s the opposite actually, as most filmmakers really want to work with him. It was just my luck that we met and that fate brought us together. Although his house has now become something of a hub for underground filmmaking in Iran.

How do you think social media has impacted that underground filmmaking movement?

N.S.: Clearly, technological development of smaller cameras has influenced and made underground filmmaking possible. If it weren’t for this equipment, it just wouldn’t be possible. Around 30% of Panahi’s last film was actually shot on an iPhone 13, after someone in the village they were filming in betrayed them. They had one night to shoot, because in the morning the government would have come for them, and so they used what they had and left. It’s very common.

Thank you so much for speaking with us.

This interview was conducted in Farsi with a translator, and edited for length and clarity.

The Witness (Shahed) had its World Premiere on September 5, 2024 at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the Orizzonti Extra Audience Award.

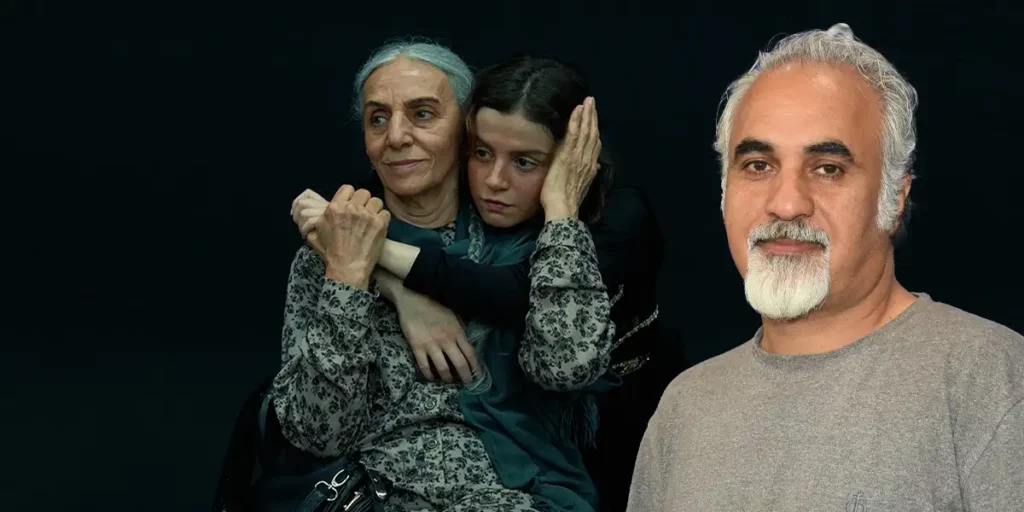

Header Credits: A still from the film / Director Nader Saeivar at the photocall (ArtHood Entertainment / G. Zucchiatti La Biennale di Venezia – ASAC)