MLK/FBI is a stellar window into the FBI’s illegal surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr., and the society that tacitly blessed its tactics.

The knowledge that the FBI improperly taped Martin Luther King Jr. for years is basically common knowledge among all those that might be the audience for a documentary such as this. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s surveillance of Dr. King is even a plot point in Ava Duvernay’s superb Selma. That tasks director Samuel Pollard (Spike Lee’s longtime editor) with finding an “in” to justify the documentary’s existence. Pollard succeeds by shifting the focus somewhat away from King himself and directly onto the FBI and, as James Comey describes it in the film, the “darkest period of the FBI’s history.”

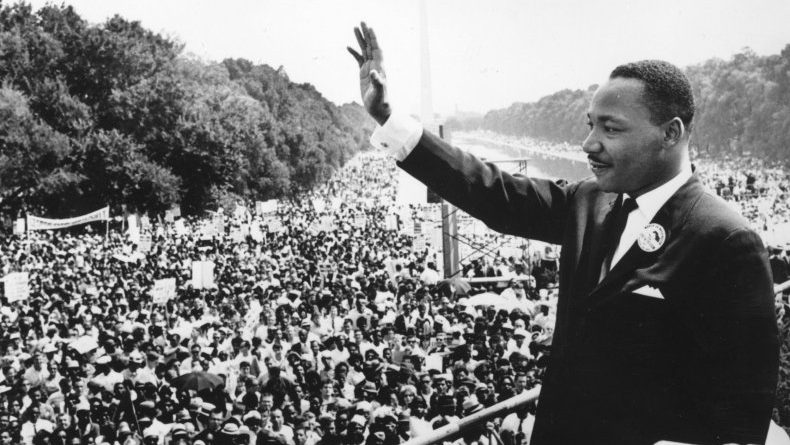

Pollard’s documentary is too smart to take the easy route and try to tell a story by digging into the prurient details of the MLK recordings. Rather, Pollard focuses on white politicians’ obsession with King’s sexuality as a lens to view the perceived threat of a black man to the 1960s’ societal hierarchy. There is no ambiguity in the Bureau’s position – to Hoover, King is the “most dangerous negro in America,” the potential messianic black figure that brings fundamental cultural change. To President Lyndon Johnson, King is an ally… so long as he stays in line with the administration’s positions.

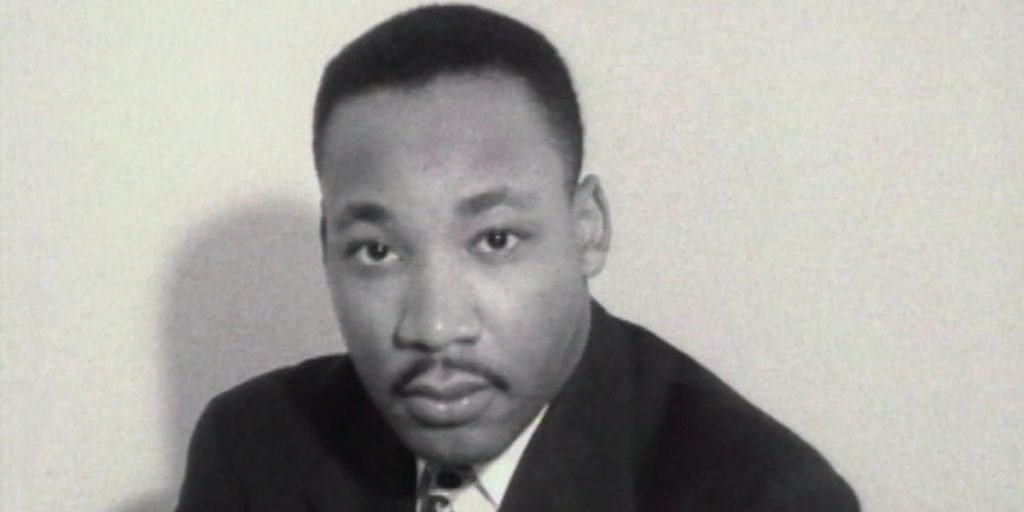

The filmmaking, here, is astounding. The restoration work on much of the 60s era footage that makes up the film is really excellent. It’s not quite up to the restoration bar set by Apollo 11, but the imagery feels vibrant in a way it likely never has before. Pollard is aided by crisp, vibrant, exciting editing from Laura Tomaselli. The interplay of historical footage, newsreels, graphic overlays, and classic era Hollywood films makes for something that moves extremely briskly.

Yes… I did say classic era Hollywood films. One of the doc’s theses is that Hollywood’s affection for G-Men stories in the Golden Age helped create an atmosphere that made it easier for someone like Hoover to run roughshod over the rights of a Martin Luther King Jr. One of the ways the film demonstrates this is through using Old Hollywood films such as Jimmy Cagney’s ‘G’ Men. Something Pollard effectively conveys that might surprise a modern viewer is how deeply unpopular King’s positions were with the majority of Americans. Hoover’s reign as the czar of the FBI saw massive widespread societal approval in part, Pollard argues, because of Hollywood’s complicity in his method of policing.

The creeping proliferation of the executive blessed surveillance is laid out with disturbing clarity. President Johnson’s shift from a supporter of King’s to someone willing to utilize the FBI’s considerable power to blackmail him is laid out in frustrating detail. How easy the shift from democracy to authoritarianism in LBJ when questioned about America’s role in the death of countless Vietnamese civilians. Pollard is too smart to say aloud the film’s meaning, but in 2020 his impart is clear.

MLK/FBI is vibrant and essential documentary filmmaking. It is one of the best documentaries of the year and, assuming it sees timely release, should deservingly compete for a trophy at the Oscars next year.

MLK/FBI was screened at the 58th New York Film Festival on Monday, September 21, 2020 and was released in US cinemas and on VOD on Friday, January 15, 2021.