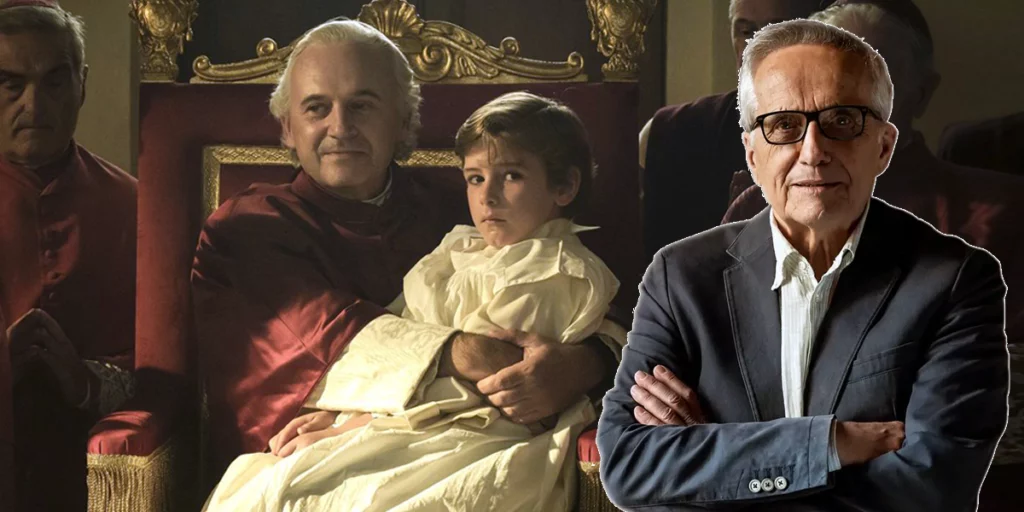

We sit down with Marco Bellocchio, director of Kidnapped (Rapito), for an interview about his new film and the Italian history that inspired it.

Kidnapped (Rapito)is a historical drama directed and co-written by Italian filmmaker Marco Bellocchio. The film, which first premiered at Cannes in May 2023 and then came out in Italian cinemas later that year, will be released in UK cinemas this week. The movie is based on true events and loosely inspired by the book “Kidnapped by the Vatican? The Unpublished Memories of Edgardo Mortara” by Vittorio Messori.

Marco Bellocchio’s Kidnapped starts in 1851 in Bologna, Italy, which was then part of the Papal States, and follows a young Jewish boy named Edgardo Mortara (Enea Sala) as he is taken from his family by the Papal States to be raised as a Catholic. As the years pass and the Mortara family desperately tries to get their son back, the film also takes us through some key historical moments in Italian history. Edgardo’s story soon becomes intertwined with that of the country’s unification, which terminates with the breach of Porta Pia in 1870 – an event that marked the defeat of Pope Pius IX (Paulo Pierobon).

As the film shows us, Edgardo is taken from his family home forcibly, as the Church quite literally kidnapped the young boy from his Jewish family after learning that he was baptised in secret, in order to raise him as a Catholic. As the movie goes on, his family’s quest to have him back becomes one with the unification of Italy and, therefore, the end of the Church’s political power and control over central regions of the country, especially Rome which remained part of the Church’s domain and only later became a part of the then newly unified Kingdom of Italy.

Almost a year after Kidnapped’s debut in Cannes, we sit down with director Marco Bellocchio to talk about his film, Italian history, and the shooting of the movie. Read the interview!

Marco Bellocchio on how he decided to tell this story in Kidnapped and the real story behind it

I know Kidnapped is based on a book, but how did you first hear about the Mortara case and how did you become interested in it?

Marco Bellocchio: I discovered it randomly: I think I was in a bookshop and found this book on the infamous Mortara case. I bought it and realized that it was written by a very Catholic and conservative writer, who took a stand against all those who acknowledged the horrible violence committed against this child. According to the author, Vittorio Messori, the fact that Mortara remained a Catholic all his life – in fact, he even became a priest, a monk, and a missionary – after his forced conversion was proof enough that there was no abuse. I don’t want to bring up the basic principles of psychology too much but actually, it is entirely possible for someone to suffer such violence and somehow unconsciously adopt it to eventually become like the perpetrator.

Throughout his life, Mortara was on good terms with his family. I remember meeting his great-grandniece: her name is Elena Mortara and she is a professor who taught in the United States. She told me that after his mother’s death, Edgardo reconnected with his siblings, despite remaining strong in his Catholic beliefs until the very end of his life. At the same time, however, in the first part of the film , we see a child who is attempting to reconcile and balance his family and the Catholic faith. He is so distressed that he can’t find the strength to side with the Pope against his family nor to go back home to his family; after all, he is just a child. In his case, there was also a stipulation from the Casa dei Catecumeni [the boarding school for the children of converted Jews] that he could only ever see his family again if they converted to Catholicism, which is just awful blackmail.

Marco Bellocchio on the use of language and authenticity in Kidnapped

I really liked the use of languages in Kidnapped. We hear the characters speak Italian, but also Latin and Hebrew. Was this intentional when writing the script?

Marco Bellocchio: Back then, Latin was still very strong in the Church, even if it was constantly becoming weaker. It is also because of my studies: much like in all Italian schools, I studied Latin during middle school and liceo classico [a high school for classical studies in Italy]. Latin is also fairly similar to Italian and I still remember it relatively well, unlike Ancient Greek.

I don’t know Hebrew at all, but we did involve various rabbis, who collaborated with us for Kidnapped. They educated the actors in the Mortara family regarding the prayers and religious rituals. In these cases, representation is not always easy: there are often objections and people question the authenticity of the culture that is being portrayed on screen . But I have to say that in our case the Jewish community did not say anything, because we respected the Jewish rituals, customs, and prayers. None of the actors is Jewish in real life, but everyone studied very diligently for the film. They learned all the prayers, especially Enea Sala; of course, children also have a wonderful memory.

On the historical and cultural context of the film

This is also very much a story based on Italian history and culture. How did your background as an Italian filmmaker influence you in the making of Kidnapped? I’m asking it keeping in mind that non-Italian directors have also considered adapting this story for the screen, especially Spielberg who was interested in adapting the story for the screen many years ago

Marco Bellocchio: Yes, and Italian directors too! I was taken by the story of Kidnapped because it is an Italian story: it’s about a Jewish family, but it’s set in Italy. I had a certain familiarity with it, which made it easier for me to approach it, both in the sense of the family life and the regional setting: Edgardo was from Bologna; I am from Piacenza; the Mortara family had eight children; my family also had eight children; we are Catholic; they were Jewish. I felt close to it in a way: they are Jewish, but they speak in Italian, with an accent from Bologna. The whole question of religion, and the conflict that the religion itself causes, also really appealed to me.

Spielberg, in particular, was looking to make a film exclusively in English, with an all-English cast. Apparently, he stopped because he could not find the child actor, but I find it difficult to believe that a machine as powerful as Hollywood would stop just because of that. Of course, everyone can do whatever they like, but he might not have appreciated and explained the turbulent and changing times in Italy at the time. After all, this story is very much situated within this moment in Italian history. He would have done something different, that is for sure. This is an international story, but it’s also very Italian.

Kidnapped spans many years, and historically some of the most important ones in Italian history. Did you feel a need to explore such a significant time in Italian history and how did you approach researching it?

M. B.: The kidnapping happens in such a unique historical moment. There was widespread change across Europe with the revolutions of 1848 [the most widespread wave of democratic revolutions across Europe]. Edgardo was not the last kidnapping by the Catholic Church, there were so many in the 18th century and this was the penultimate one, but it was a violent act in a larger political context of turmoil, transformation, and upheaval. If it had happened in another time and period, it would have gone unnoticed. Instead, the Mortara case reached the big European capitals.

It became an international case as many important people took the side of the Mortara’s family. Even those who loaned money to the Church, like the Rothschild family, and had the power to bankrupt the Church became involved, but the Pope never faltered. Historically, Pius IX was only defeated years later, with the unification of Rome. This is also present in the last part of Kidnapped as we portrayed the symbolic and final victory in the conflict between the Kingdom of Italy and the Church, the Breach of Porta Pia.

This was a very significant historical moment for the future of the country too. The Pope would be confined to the Vatican after that, a lot less powerful than before, until the Fascist government established a peace treaty with the Church, granting it a lot of privileges, like the teaching of Catholic religion in schools.

This is a very historical film that goes beyond the singular family story. Did you feel a need to analyse one of the most important moments of Italian history as you have done in previous movies as well?

M.B.: This is very interesting to me. I speak for myself, but I like it when a small and private story is placed within a much wider historical context. It is the same with Vincere (2009)for example. It is the story of the young love between Ida Dalser and Mussolini and they have a son together. She becomes lovesick and does not want to live without Mussolini, who has now become the head of the state and a dictator. Kidnapped is a tiny personal story set during the end of the papal state that had been around for two thousand years.

On the filming of Kidnapped

What inspired you visually for the aesthetics of Kidnapped? Were there any challenges in shooting a movie set so long in the past?

Marco Bellocchio – Some historical buildings are, of course, still there, but there was not much else in Rome. There is so much to rebuild, the areas where these people used to live are all gone now. I could, however, use digital means; for example, when they arrive in Rome, I wanted to portray the city from the water. We had to recreate a lot of buildings, and some were added in post-production too. It is also implausible: they are coming from the sea, so it doesn’t make sense that they would arrive on the river Tiber, but it is one of the liberties we wanted to take. St Peter’s Basilica, Castel Sant’Angelo, and the river are all symbolic images too. With the technology of today, it is possible to recreate the imagery of the time, even almost perfectly. Of course, we had a big budget behind too, but we did not have the actual setting. Even with the battle scenes, we had to recreate a real battle in Kidnapped with explosions and soldiers near the walls of Rome to show the Breach of Porta Pia.

When you work with historical reconstructions, you have to imagine a new version of reality. I wanted to recreate the historical setting, especially for the funeral procession. We obviously could not do anything in St Peter, so we started the procession just outside as the camera preceded it, moving towards Castel Sant’Angelo. In the first part of the sequence, we had to show the Basilica of St Peter in the background: today, it is very lit up, so we had to work closely on every detail to remove every single light: we couldn’t turn off the lights in St Peter in real life! But we did it because it was very important to show Pius IX leaving from St Peter and crossing the bridge. It is very similar when we arrive in Castel Sant’Angelo: there is a whole neighbourhood behind it that was rebuilt during the Fascist time, Via della Conciliazione did not exist in the 18th century for example, so we had to work on creating the historical dimension of that too. You can obtain very good results by working on erasing elements like this.

A key part of Kidnapped is the performance of Enea Sala as Edgardo: how did you work with him to fully explore the role?

M. B.: It’s interesting because Enea is a kid of the modern age: his family is not religious, he was not baptised or ever set foot into a Church. And yet he still learned, he combined the acting with the prayers and religious aspects. He also portrayed the family situation very well. His family circumstances were not easy, because his mother was sick and later died: the intensity of his acting goes back to his very own pain and grief in his personal life.

How did you combine the historical elements with fiction in the film?

M. B.: As narrated in Edgardo’s – memoir, which is included in Messori’s book, as an adult, he had long and mysterious illnesses, causing him to get sick easily and for long periods of time. He used to have leeches applied to him, which was considered a remedy at the time because they suck blood, and he talks about it in his autobiography. We actually filmed a scene like that with Edgardo as an adult, but it did not end up in Kidnapped because the film was too long. He also writes about the scene where he almost causes the Pope to fall which is in the film and happened in real life Pius IX was very upset: he shouted at Edgardo and humiliated him in front of everyone, this is something that happened. I think there was probably something in his subconscious that came out at times rather suddenly, like a sort of rebellion. Something in him was not completely at peace with religion, and with having embraced Catholicism in such a way.

One of the final scenes, when Edgardo joins the rioters in their attempt to throw Pius IX’s body into the river Tiber, is also based on a real event. When Pius IX’s body was transported from St Peter’s Basilica to the Basilica of Saint Lawrence – he is still buried there now, you can even visit – Rome was already part of the Kingdom of Italy. An anti-Catholic group attacked the convoy and tried to throw his body into the river. And Edgardo was actually there: now, the fact that he briefly disassociated, or was taken by momentary madness, and joined them is a poetic licence. I think his life was incredibly sad, and this is visible at the end of Kidnapped as well: his attempt to baptise his mother is truly an actor of desperation that once again he recovers from.

Marco Bellocchio on the relevance of this film in today’s culture

We talked about how Kidnapped is an Italian film, and also a very historical one, but it also feels very relevant today. Do you think this film can be relevant outside Italian national borders in a modern context and with an international audience?

Marco Bellocchio: Well, yes. I only have one direct experience of this, as Kidnapped was distributed in France recently and was very successful. It was also a very delicate time, because it was after October 7 [which marked the first attack that initiated the Israel-Hamas war], so I was not entirely sure how the film would do. I know there is a very large Jewish community in France but I understood that there could be certain doubts and fear in this climate. But the movie did well, just as well as it did in Italy, where it premiered before the armed conflict escalating in Gaza as part of the conflict between Israel and Palestine. – Now it will be interesting to see how it goes with the UK release!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Kidnapped (Rapito) will be released in UK cinemas and on Curzon Home Cinema from 26 April, 2024. Read our review of There’s Still Tomorrow (C’è Ancora Domani).

loudandclearreviews.com

loudandclearreviews.comHeader credits: (L-R) Curzon, Anna Camerlingo