Often cited as the worst film ever made, the infamous Manos: The Hands of Fate fails at every aspect of moviemaking, or is this part of its genius?

The year was 1966. One day, in El Paso, Texas, Harold P. Warren was having coffee with a friend, screenwriter Stirling Silliphant. At one point during their conversation, Warren claimed that making a horror film was easy, and bet Silliphant that he could make a feature length horror film on his own. Thus are the strange origins of Manos: The Hands of Fate, a film outlined on a napkin, made by technically inexperienced theater actors, on a miniscule budget of $19,000 (which, adjusting for inflation, is about $150,000 now). Warren’s opus has gone down in history as one of the worst films ever made, but is it?

Manos: The Hands of Fate fails at nearly every aspect of filmmaking. This is undeniable. The use of blurred focus feels completely accidental, the performances are stilted and lack even a modicum of humanity, every line of dialogue is dubbed, and things just happen with little to no explanation. Watching the film is to view a disaster unfold. It is a product of incomparable incompetence. And yet, is this secretly part of the film’s genius? Because of the sheer ineptitude on display, the film transcends traditional notions of filmmaking and becomes something else entirely. Something avant-garde even.

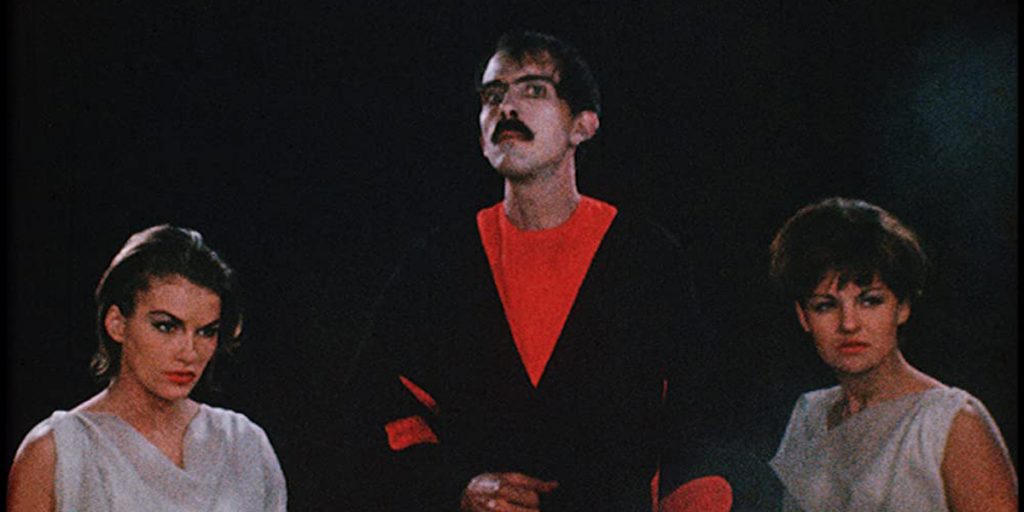

The first sign of this film’s experimental brilliance is when we meet the character of Torgo (John Reynolds). After becoming lost, the main characters (a family of three and their dog) stumble upon a peculiar house in the middle of the desert. Thinking there might be a phone in the home, they knock on the door and Torgo greets them. Reynolds’ performance as Torgo is magnificent: his acting is so enticingly odd it transforms into performance art.

Torgo is always jittering and moving with a frenzied, confused, lustful look in his eyes. He never stays still, he is constantly vibrating, shaking nervously. Because of the persistent movement in this very physical performance, Torgo is a completely unpredictable figure. You never know what he might do next. Reynolds’ acting elevates a standard creepy servant character into a truly menacing and malevolent force. It is a performance so singularly strange that you cannot take your eyes off him, and yet he is so unnerving you want to look away.

Furthermore, the filmmaking techniques defy understanding. Characters will appear in one part of the house in one shot, then mysteriously teleport to a different part in the following shot. There are also purposeless scenes showing a young couple making out in a car somewhere in the countryside. Some shots are too long, others are too short, creating a disjointed and uneven sense of pacing that is beyond the realm of normalcy.

And I cannot forget the bizarre, lengthy sequence of women arguing whether to kill the family or not. Their dialogue does not match the movement of their mouths, and they perform as if they were told to simply pantomime. I am not exaggerating when I say that every single decision in Manos confounds the mind. This is another aspect of its accidental genius. Warren crafts an entirely new cinematic language by breaking every conceivable moviemaking rule. The film has a similarly jazzy energy as Jean-Luc Godard’s French New Wave classic, Breathless, though Manos is a much more manic and hilarious experience.

By breaking every cinematic rule, the film also creates a dense, eerie atmosphere where anything is possible. This is where the horror comes in. Through the avant-garde techniques employed in the movie, the viewer is always left eerily uncomfortable. There is nothing in reality one can associate with the people or events in Manos, and that’s exactly what makes it an effective, if unconventional horror flick. With nothing to ground the viewer, you become catapulted in a nightmarish fever dream of sex cults and wizardry. Similarly, last year’s terrifying disaster, Cats, created an atmosphere untethered from reality. Cats borrowed Manos’ technique of utter incompetence and accidentally created a captivating horror film. A look into an alternate dimension.

In the end, Harold P. Warren won his bet. He had, at the very least, made a horror movie. One could debate how successful he was at making a horror movie, but the fact remains that he made one. How many of us can say we made a feature length film just to win a bet? Hell, how many of us have wanted to create anything and have not done so? Manos: The Hands of Fate is a pure artistic vision.

It is the creation of a group of friends who had no idea what they were doing. There is beauty in that. The final version of Manos was probably not what Warren had intended. Nevertheless, he made a lasting cinematic statement, one that eschews all traditional notions of filmmaking in favor of wildly experimental, uncomfortable, and mind-boggling tactics. Without a doubt, Manos: The Hands of Fate has paved the way for many of the bad movies that have followed, resulting in an unforeseen legacy within the wider film canon.