Labyrinth of Cinema is a thoughtful and exciting rumination on the art of film, and serves as a farewell from its director, the late Nobuhiko Obayashi.

Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Labyrinth of Cinema is a difficult film to digest. At 3 hours long, it is an undeniable epic, exploring countless ideas, taking the viewer through diverging thematic pathways, tangents, and emulating myriad styles of Japanese cinema, specifically war films of the 1940s. On top of all that, it serves as a history lesson, a rumination on the purpose of cinema, and as Obayashi’s own swan song. Moments feel elegiac, but, in a way, the film never ends. A narrator notes that the film will be interrupted by a song and the song plays as the credits start to roll. Fact and fiction merge throughout Labyrinth of Cinema, so even though the film technically ends, its ideas, boundless creativity, and sheer earnestness live on and touch our lives long after the screen goes dark.

While much of the film is a history lesson of wartime Japanese cinema, and a history of Japanese wars throughout the centuries, it never becomes dry, thanks to the thoughtful and heartfelt screenplay Obayashi wrote along with Kazuya Konaka and Tadashi Naito. The visual style of the film is its own beast entirely, deliberately digital, chaotically edited; cuts are constantly smashing, jumping, and zooming into each other. And, while I personally wasn’t expecting the film’s overwhelmingly digital style, I grew to like it quite a lot. It perfectly encapsulates Obayashi’s postmodern pop approach, like a Godard and Nabwana IGG collaboration: a critical historical survey that meets freewheeling enjoyment of cinema.

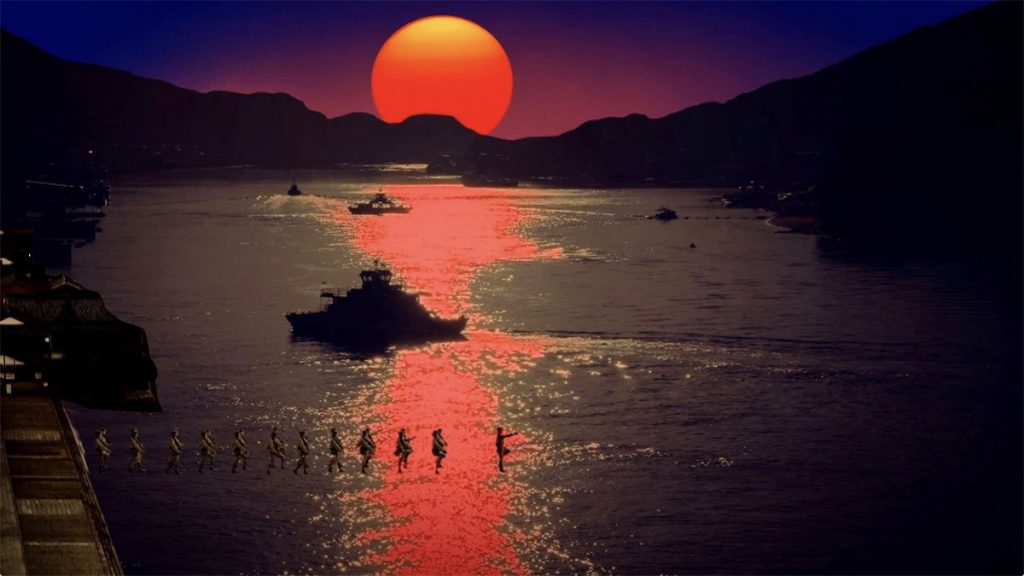

At times, the form of Labyrinth of Cinema feels cheap and even purposefully cheesy, with its abundance of green screens and schlocky computer effects. And while it took me some time to get used to its idiosyncratic visual style, the form helps articulate one of the key themes of the film: there is truth in lies. There are key human truths surrounding memory and remembrance that the film highlights, all while taking place in an obviously fake, at times garish cinematic world. But Obayashi has never concerned himself with realism, and the lies inherent in the cinematic language seem more honest and open when not trying to be hidden with invisible editing, long takes, and a gritty color palette. One moment that stood out to me is when the characters walk around green-screened archival images of Hiroshima before it was bombed. These images of the past collide with images of present day Hiroshima, with characters placed on top of both. An interesting dissonance emerges, here, between past and present, even though the film remains steadfastly artificial. These are cinematic images of history, but they still hold weight; they’re obfuscated and green-screened, but, even within all the lies and techniques of film, they still hold incredible historical truth. If there is truth in lies, what, then, is cinema? Its own truth? A fabrication? A delusion?

The main plot of the film concerns itself with three characters being transported directly into Japanese war films. They must reckon with their status as audience members and also as participants in the films they find themselves in. Obayashi implicates them directly, one of them cries out that they are only passive viewers of cinema and history, but the film argues that we can’t just sit idly by and let the world revolve around us. We must act, for the present and for the future. Cinema can only do so much: it can help remember and educate, inform and entertain, but it can also lure us into a false sense of security and passivity. It is in this way that cinema is a trap. One character is a self-proclaimed cinephile, and he must learn to exist outside of film, to live in, experience, and change the real world.

Cinema is also inextricably tied to history, not only as a part of it, but also for the stories it tells and doesn’t tell. It may even be the way most people consume history. We learn stories of Japanese history that cinema has rarely, if ever, touched: that the Japanese government murdered over 800 Okinawans during WWII, and that, in a civil war in the year 1968, a ragtag battalion of women and children fought and died for what they thought was right. Who does cinema and history exclude? The perspectives of the marginalized and exploited.

Ultimately, Labyrinth of Cinema sees film as a way to remember the past, to remember those who lived and those who died, and perhaps you may find yourself, the self you’re looking for, among the sea of images. Obayashi’s final film is an ode to film and those who love it, it decries war and violence and seeks a world where there is love, peace, and empathy. And, while cinema can be used as a tool for stories that are important to us to live on, it is not an end. I wish I could spend my whole life watching movies, but that would not make for the most fulfilling life possible, and that would do nothing to strive for the changes I want to see in the world. I was expecting Labyrinth of Cinema to be a farewell to the art form, and, in many ways, it is, but it’s also a greeting, a recollection, a rumination on a country’s history and art, and a hopeful yearning for a better future. If there are two things that cinema, history, and humanity all have in common, it is our shared ability to remember and forget.

Labyrinth of Cinema will be released in New York at The Metrograph on October 20 and in Los Angeles at The Lumiere Cinema on October 29, with more regional dates to follow.