We interview Kensuke’s Kingdom directors Kirk Hendry and Neil Boyle on adapting the book to film, bringing it to life, and the history and future of the team.

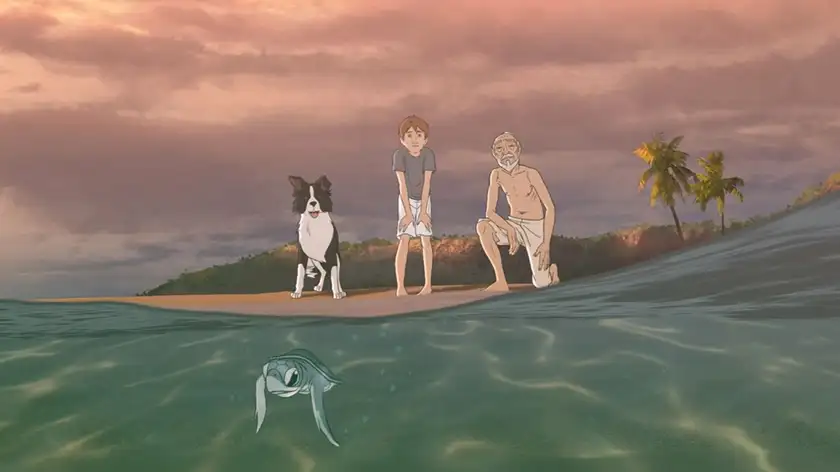

Kensuke’s Kingdom is a British animated film directed by Kirk Hendry and Neil Boyle and based on the book of the same name by Michael Morpurgo. Aaron MacGregor stars as Michael, a boy who is stranded with his dog on a remote island. They meet and befriend Kensuke (Ken Watanabe), a former Japanese soldier who’s been stranded there for years. The original story is a childhood treasure for many in the UK, and it was a great pleasure getting to watch this simple, heartfelt rendition a few months back. Recently, we had the opportunity to interview Hendry and Boyle and discuss the process of adapting the book to film, bringing the vision to life, and what lies in the creative team’s history and future.

Kirk Hendry and Neil Boyle on Adapting the Kensuke’s Kingdom Book to Film

What experience did you have with the book? Were any other books inspirations for you?

Kirk Hendry: The book is on the curriculum over here in the UK. There are a lot of 28-year-olds walking around who have read it.

Neil Boyle: We hadn’t read the book when Kirk and I were approached about the film, though. We were sent the screenplay, we both read that first, and then we obviously went back to read the book. It was interesting for us to start with the screenplay and go backwards. But there’s a really famous writer in the UK called Enid Blyton, who wrote these adventure stories for kids in the 30s and 40s. There’s one where this little gang of kids goes off to an island and builds a little den for them to live in. So, as a kid, I definitely grew up with these kinds of stories, if not this actual book.

In the book, Kensuke and Michael are eventually able to speak to each other, but they never can in the movie. How was that decision made?

Kirk Hendry: That was one of screenplay writer Frank Cottrell Boyce’s key innovations when he made the adaptation. When we read the script, we saw that this presented an opportunity for silent filmmaking, which is what Neil and I really like: using blocking, editing, music, and sound design to really tell the story and not have the characters just speak it at you. You draw the audience in a bit more, because they’ve got to play detective to work out what’s going on. It’s those kinds of films we always get particularly engaged with when we watch, so we saw this as an opportunity to do that.

But also, thematically, it brilliantly reiterated the themes of Michael Morpurgo’s book. You’ve got people who can’t communicate properly, who can’t connect at all through language. Everybody on the island – the humans and the animals – can’t connect through a spoken language, so they’ve got to find other ways. How do you bridge those gaps when you’ve got so many different things going against you, whether it’s age, culture, language, or species? They all managed to do that in the story, which is so wonderful, and how that relationship develops between Michael and Kensuke is really the crux of the story.

Kirk Hendry and Neil Boyle on Bringing Kensuke’s Kingdom to Life

What was it like for everyone to form voice chemistry with each other’s characters?

Neil Boyle: Most of our cast actually had to work separately, because we started recording for the film during COVID lockdowns. Though Aaron got to do scenes with Raffey Cassidy [who plays his sister], he did his work with Ken Watanabe separately. We had done a rough storyboard version of the film that we could show the cast beforehand, so they got a sense of the action and blocking, how far apart they were from each other, and so on, and they could have a picture in their head of what was going on in the film. However, we generally switched that off and just let them imagine all that, because we were very keen for our cast to feel they could experiment and try things out.

We had some fun times. Aaron was just remembering a scene where Michael has to eat fish for the first time and finds it disgusting. Aaron in real life really doesn’t like fish, so he asked if we minded for him to eat something else. We said that’s fine, so somebody ran out to a grocery store around the corner and came back with little strips of chicken, and he stuffed himself with that. Similarly, Cillian Murphy was stuffing himself with biscuits during an eating scene on the boat, which he loved. We kept saying, “It’s fine, Cillian, we like that,” after some takes, and he’d just go, “No, I’d just like to do one more please.” So, that went very well.

What was your thought process as you presented Kensuke’s backstory?

Kirk Hendry: We used an experimental style to tell Kensuke’s backstory, but we originally had a very complicated way we were going to do that. It was something that had plagued us for quite a while, regarding how we’d give enough information to the audience and Michael. We were going to have the paintings of his family come to life on the wall, and then we had an idea of a paint drip going into a coconut shell of water, the camera following the drip down, and then the drip making shapes in the water of the backstory’s setting.

But in the end, we thought it was ridiculously overcomplicated, and the simplest answer was right in front of us. You know Kensuke has the paintings, which creates the memory trigger, and then you just go inside his head. Michael doesn’t see the backstory or what happened, but he knows he has a family because he’s seen the pictures. So, that’s enough to trigger him asking, “How long was this when you last saw them? How long am I going to be here?” It just naturally fed into a lot of the storytelling. Often, the best way of doing something is right in front of your nose, but you take a very long, convoluted way to find it.

How did you decide to use the sketch-like animation style for the film?

Neil Boyle: Generally, we went for a very naturalistic style. It’s important to avoid having anything in here feel cartoony, because the emotions in the story are very subtle and complex. You need to feel like Michael really could starve to death or dehydrate, so he can’t be a cartoon character. He’s got to be realistic enough. But having said that, we’re not making a live-action movie. Something Kirk and I liked to do with certain sequences was reflect how these characters feel in the style of the animation. So, although the bulk of the movie is quite naturalistic, we can sometimes go inside the character’s head and see the world through their eyes. When Michael is washed up on the island to start out, he’s literally in a fog, confused as to where he is before the landscape comes through. Animation is the perfect medium for the story to get inside the characters’ heads like that.

The History and Future of the Kensuke’s Kingdom Team

What kind of past experience did the animators have?

Neil Boyle: A tremendous number of young new animators on the film came straight out of art school or college. This was their first ever job, and we even trained them on the job. They were obviously full of enthusiasm and energy and a desire to show us what they could do, which was brilliant for us. But for the animals, we had a terrific animator that Kirk and I had both worked with before: Ludivine Berthouloux. She helped us storyboard the film, and she was doing such beautiful drawings of Stella the dog, so we gave the first little bits of animation to her. She did so well that even when we brought on other animators, everyone that worked on an animal would show their shots to Ludivine to get notes or her approval. She’s just so good at drawing animals that can’t use spoken language and using all kinds of little clues to show what they’re feeling – again, without getting cartoony. You’ve got examples like how Stella would have her ears or tail a certain way, or how she’d cower or be up straight. So, she was a fabulous artist for us on this film.

Now that you’ve gotten a feature film out, where do you see yourselves going from here?

Kirk Hendry: Doing more. We’ve got various projects in development at the moment. The thing with feature films and why it’s so hard to get them off the ground is because the financing is so hard to make happen. It took us eight years since we were on board with this project to raise the funds, and I think the original producer – Sarah Radclyffe – optioned the book over twenty years ago. So, for her and Michael Morpurgo, it’s been a long journey. Independent, animated European features are very, very tricky to get off the ground. But we’re involved in various things now, and hopefully one of them will happen sometime.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Kensuke’s Kingdom was released in theaters in the U.S. and Canada on October 18, 2024.