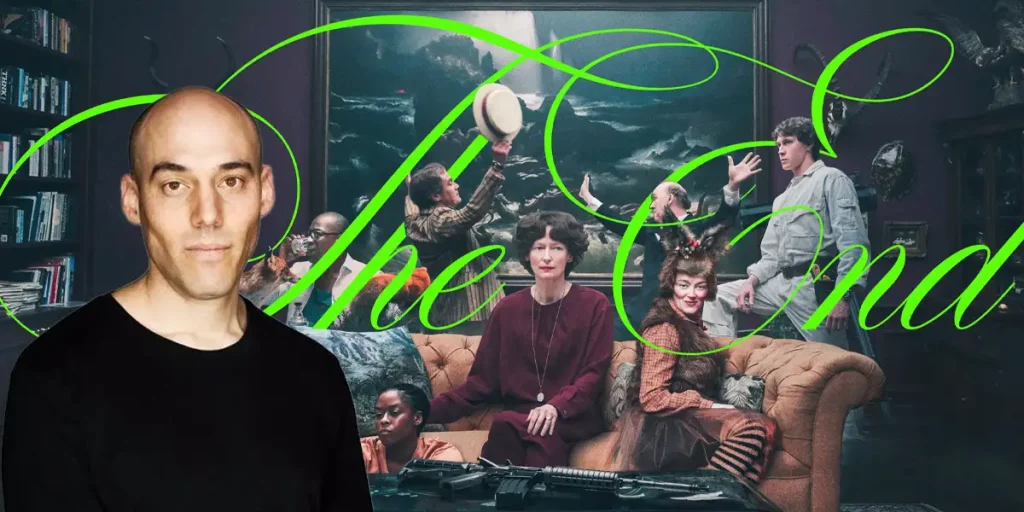

Ahead of the U.K. release of The End, we interview writer-director Joshua Oppenheimer about oil barons, empathy and existentialist dread.

Amongst the raft of ‘dark’ musicals that hit the screens in 2024, one film stood out from the rest. The End marks the narrative debut of writer-director Joshua Oppenheimer and, much like its director, it’s eloquent, memorable and passionate in its themes. This musical tale of a wealthy family and their assistants living in an underground bunker decades on from ecological catastrophe has obvious messaging regarding climate change, but it also engages in deeper conversations about self-delusion and the lies we all tell ourselves. All this is conveyed by a confident camera sweeping across an elegantly minimal set, and committed performances from musical first-timers like Tilda Swinton, George Mackay and Michael Shannon.

Oppenheimer is the acclaimed director behind The Act of Killing, the remarkable documentary in which former Indonesian Army recruits act out their acts of mass murder in support of president Suharto in the country in the mid-1960s. That film and its equally impressive follow-up The Look of Silence define Oppenheimer’s career to this point, but The End continues his thematic throughlines of denial and self-aggrandisement with verve and heart. We meet him ahead of the movie’s U.K. release to discuss ideas, individualism, and inaction. Read the interview below!

*This interview contains spoilers for The End.*

Joshua Oppenheimer on the genesis of The End

It’s been over a decade since the release of your previous film, The Look of Silence. Why did you take so long between that and The End?

Joshua Oppenheimer: It didn’t take long; every time I film, it takes about this amount of time! [laughs] [The Look of Silence and The Act of Killing were companion pieces, and Oppenheimer’s first theatrically released films].

The End had a funny evolution. First, it began as a documentary, among other documentaries. I was wanting to make a third film in Indonesia, about the oligarchs who enrich themselves by exploiting a nation that was terrified of them, and I was banned from returning there. I started investigating billionaires elsewhere who’d made their money through violence, and I found an oil tycoon who had used violence to obtain his oil, his drilling rights and oil concessions, and he was purchasing a bunker like the one in The End for his family.

As I was developing a documentary with him, I visited this bunker with him, and suddenly I couldn’t think of anything else. I was just captivated by the questions of guilt and self-deception inherent in the situation, because of this idea that they would move into this place and tell themselves that nothing had changed, yet they were trying to create a sense of continuity. It reminded me very much of The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, in which I create, even though decades have passed, a sense of continuity with the horrors of the genocide.

Did the COVID-19 pandemic hold that research and production up?

J.O.: I was working on two other documentary nonfiction projects, one in Japan, one in Greenland, but both of them had to stop when the pandemic hit, because both of those countries were completely locked down. There was no visiting them at all. Then I really switched my focus to The End.

How did you find the shift from documentary to narrative filmmaking?

J.O.: When you make a new musical, it’s not like you just write a script and you make the film, which was a career change for me. I really was determined to take the craft of it seriously at every step. There’s a learning curve, which took some time, but also it’s like three writing processes. You write a script, then you write songs, then you find you have a Frankenstein problem, where the script has ruined your beautiful songs, and your songs have ruined your script. Then you have to work to integrate them into a single film, a single piece of music, a single composition, before you can even begin to think about casting and all the complexities of pre-production.

Of course, making a musical is notably more complicated than making a movie where people don’t sing, and that’s just inherent to the genre. It’s not a speedy form, unless you’re taking a pre-existing musical. Yes, it was long, but I also think people who’ve appreciated the film, and who have an idea about filmmaking, might say, “Yeah, it looks like that took about eight years.”

The cast of The End is notable for featuring actors who’ve never appeared in musicals. How did you decide these were the actors for these parts?

J.O.: For these roles, what you’d expect of the actors is courage and a desire to be thrown outside of their comfort zone and to explore the depths of their vulnerability, and that’s what you see in these actors. You see not an ensemble, but a doomsday cult that signed up for the Rapture. They’re so committed, and I was looking for actors whose faces would register every flicker of doubt and every pang of longing, so that the subtext inherent in speech would be exhausted, so that the lift into song would feel inevitable.

All these actors have that real, ultra-sensitive, refined instrument in their faces, and that physicality of expression. They’re courageous, too; rather than shrink from the idea of singing, they just embraced it, even though Tilda had never sung in a film before. Of course, I had to make sure they were truly musical and able to not only carry what is some of the most challenging music in the musical repertoire at the moment, but also take these painful emotional journeys through song. They were just up for the challenge. There was no trying to convince them. As Tilda put it, any actor who says ‘yes’ to this is the right person. They’re destined to do it.

Joshua Oppenheimer on the appeal of the musical

Prior to The End, you played with musical form in The Act of Killing. What inspires you to make musicals from such dark material?

Joshua Oppenheimer: I think I have to have a genuine appreciation for the music, or I would just find it loathsome. I also think there’s something tragic to the point of being an allegory for the greatest problems of our time, inherent in the escapism and delusion baked into the form. The idea in the Golden Age musical that you can passively bury your head in the sand, no matter what’s happening in the world and the sun will come out tomorrow, is, I think, a lie we tell ourselves. That lie is responsible for, at this point in our history as a species, leading us right over the edge of the abyss.

I think we live in a society where we and our families are addressed as isolated individuals. COVID didn’t help, but my obsession with this predates the pandemic. We’re addressed as isolated bubbles, but we need collective decision, collective action, really profound solidarity and collective resistance and transformational change to how we live on this planet if we’re not going to go extinct. At the same time, our individual lives are rendered less than they might otherwise be, when we put ourselves ahead of everything else, and we squander the one chance each and every one of us have as individuals to build meaningful lives on this beautiful planet when we prioritize self interest above everything else.

For me, the escapist delusion of the musical resonates with the escapism of self-staging in social media, and with how we kind of how we are addressed, to consider individualized responses to everything, as if we can solve the most existential crisis our species has ever faced with lifestyle adjustments, without questioning how we actually live. I think we all know it’s doomed to fail, and that leads to despair, cynicism, and disengagement.

Do you see this societal need for escapism as a defining theme for you? The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence are all about the shunning of responsibility.

J.O.: Yes, but we fail to grapple with the real meaning of our own mortality in our individual lives too. It’s in every one of our natures to grow old, to get sick, to lose the people we love and to die. The question is not how we’ll live on for as long as possible, or how we can just live in denial of that, but how shall we live given that. So for me, this is a genre that haunts me and makes me weep, because the music is beautiful, but also makes me weep an extra kind of bitter tear because I perceive the tragedy of that self-deception. It makes me long to bring the viewer to a point where they’re crying that same bitter tear by the end. They’re thinking, “Oh no, don’t sing this beautiful music to yourself and lie to yourself”, because it’s not consoling for anything. It’s the source of the catastrophe.

I think it’s not an accident that The Act of Killing ends with a big musical number, which moves viewers to tears because they’re perceiving the cost of that escapism and that lie on a whole society. In The End, the end comes as Moses Ingram’s character surrenders: the last honest human being in this world gives up because the only source of comfort left for her is to try to walk the path of the family’s self-deception. She’s struggling to suppress her tears, but she tries to convince herself, with the rest of her family, that their future is bright, even as she faces the abyss.

The fact that that happens in a musical number brings together all the themes and the melodies we’ve heard through the film up to that point. Just in its grammar, it steps out of the 1950s musicals that held our culture together now at a time when we all know nothing holds neither our cultures nor our democracies, nor even the atmosphere together. For me, that’s deeply implicating.

The irony of The End is that the musicality isn’t trying to overcome the post-apocalyptic setting, but reinforces it.

J.O.: Yeah, because it’s not just the tragic mistakes of these characters that we can learn from. It’s baked into the logic of our culture. I think that’s the true sense in which The End is a post-apocalyptic film. The word ‘apocalypse’, in its etymology, means ‘revelation’, the revealing, the uncovering. That’s why the book of Revelation is called that in English, but in Greek it’s the book of Apocalypse. We are living post-revelation in the sense that we’re the first humans on this planet to know that, if we continue as we are, we will go extinct.

We are the first humans to know that our end is already baked into our present, and that it’s a very specific set of events related to climate change. In a sense, we are living after the apocalypse, after the revelation. That demands that we come together, collectively and radically, to reassess how we live. How must we change the way we are living structurally on this earth to prevent this?

Joshua Oppenheimer on 2024, the year of the ‘dark’ musical

2024 was a year for the ‘dark’ or ‘dour’ musical in film: The End, Emilia Pérez, Joker: Folie à Deux. Do you think that stems from that pervading sense of existential ennui we seem to be living through at the moment?

Joshua Oppenheimer.: I think that the Golden Age musical has this kind of cliché about it. I’m thinking more of the Broadway musicals, but it’s the idea that characters sing when their truth is too big for speech. It’s a cliché about musicals, and I think the sense that that is always a lie, that what they’re singing is often a delusion, is something that people are feeling, because we’re living in this post-apocalyptic moment where we know things are really going off the rails. But at the same time, I think you can work with that in different ways. To be satirical with it is the easiest way is to be tongue-in-cheek about it. Another possibility is to reinvent the Brechtian way of working with song, and I think that’s closer to what Emilia Pérez does.

I think what’s special about The End is that, as the characters feel all their excuses unravel, or they feel pangs of forbidden longing, they reach desperately for new lies through music, and struggle through song to convince themselves of new anthems to get them through the day. They can’t face the unvarnished truth, and they’re on a journey through that longing that transforms them, and opens up new possibilities of hope.

The idea behind the music is to bring emotions to the fore rather than underline what’s already been said, correct?

J.O.: These are active journeys for the characters. Rather than illustrate the luminously beautiful lies into which the characters escape through song, by creating these fantasy production numbers we’re watching characters desperately struggling and failing to believe. The rich, complex counterpoint that [composer] Josh Schmidt has written to kind of accompany these luminous lies acts as an undertow. It pulls them down towards the truth, and so you’re watching as they desperately try to lift themselves up through song.

Through the act of self deception, the act of singing, and being pulled closer to truth, before no longer being able to sing, the truth finally screams through in the silence. In these silences when they can’t sing, and then they try again, that makes the songs very sincere and dramatically active, and also demands these long takes. If you have characters who are performing with the commitment that this cast performs, all you can really do is bear witness to them.

Joshua Oppenheimer on characters and critics

How do you respond to criticisms that you’re making these polluting energy barons of characters empathetic?

Joshua Oppenheimer: It’s exactly the same criticism that was leveled against The Act of Killing. How can you not present the bad guys as monsters? We live in a culture that tells that same story again and again and again: that the world is divided into good guys and bad guys. It entertains us by having us enjoy watching the bad guys get their comeuppance, and ultimately reassure us that we’re like the good guys. I think the algorithms that drive the streamers have really made this problem much, much worse.

When I was a child, I remember being asked, “Do you like movies with happy endings or sad endings?” My family was going through a divorce, and I honestly would answer “I prefer the movies that end sadly, because they show what my life is like.” My parents weren’t perfect, the world around me wasn’t perfect, and now such movies hardly exist. If you think of pretty notable films like Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, that has a tragic ending where the characters are deeply flawed. The same is true of Nashville: another tragic ending. Even if it’s a comedy and a musical, the characters are still deeply flawed, but we don’t tell those stories anymore, and audiences may be accustomed to that now.

The bunker in The End is not just the bunker you see on screen. Every time you read a story about the climate change, or about the genocide in Gaza, or about people drowning in the Mediterranean Sea while trying to escape conditions of misery that we all knowingly impose upon them for our cheap food and clothing, we search and response to these stories for just the right outraged or heartbroken emoji, and post it to drive a tiny bit of traffic to someone else’s for-profit social media platform. We give ourselves the illusion that we’ve done something, and give ourselves permission to shift our attention to something more fun, all the while deepening our dopamine-addled addiction to this kind of interaction with our screens. We have willingly signed up for the very same bunker that you see in The End.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The End will be released in cinemas in the UK & Ireland on March 28, 2025. In the US and Canada, the film is now available to watch on digital and on demand. Read our review of The End!