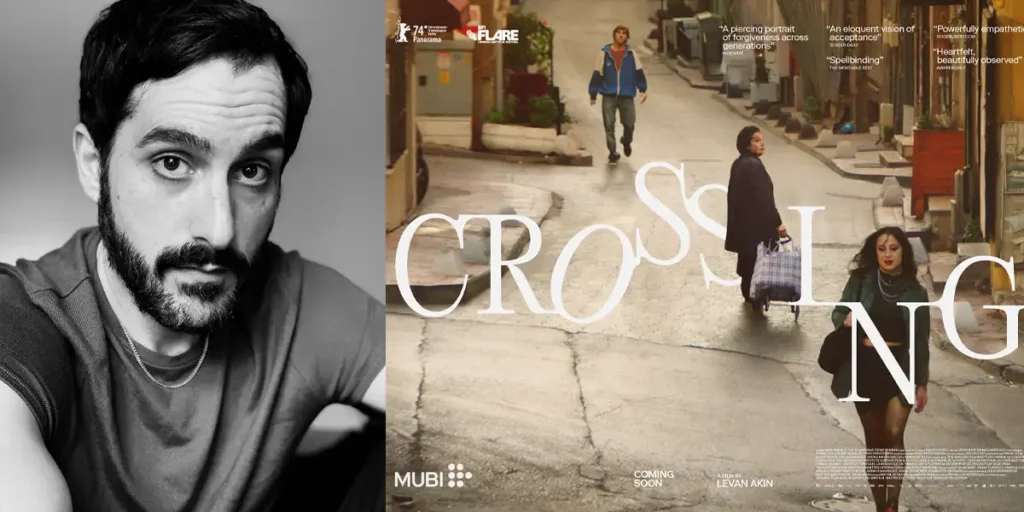

We sat down for an interview with director/writer Levan Akin to discuss his latest film, Crossing, a sweeping, layered drama that builds on the power of his previous release.

Levan Akin continues his remarkable streak for complex, vibrant dramas with Crossing, which focusses on and challenges notions of tradition. This layered border-hopping drama follows Lia (Mzia Arabuli) and Achi’s (Lucas Kankava) journey to Istanbul, in search of the former’s transgender niece, Tekla. In Turkey’s largest city, they meet a host of vibrant and detailed characters, including Evrim, a trans rights lawyer. Akin’s previous film, And Then We Danced, similarly stunned audiences in 2019 with its vibrant depiction of a gay love affair existing amidst the intense homophobia of Georgian society.

Akin’s patient and considered writing along with warm and evocative cinematography by Lisabi Fridell sees the story of Crossing unfurl in an unhurried but highly resonant way. Essentially telling the stories of three lead characters, plus many supporting ones, Crossing somehow never feels cluttered, and constantly feels invigorating and deeply important.

Crossing had its world premiere at the 74th Berlin International Film Festival. Before the film’s theatrical release on 19 July, we sat down with director/writer Levan Akin to discuss the staggering depth of Crossing, how it challenges discrimination, and how he simply wanted to make a film that felt, above all else, earnest.

Rich Worlds & Characters: Levan Akin On Portraying Istanbul And Its People In Crossing

I saw Crossing at the Berlin Film Festival earlier in 2024 and loved the film so much. I particularly enjoyed the portrayal of Istanbul in the film. What is your relationship to this city and how did you approach depicting it on screen?

Levan Akin: I used to spend time there as a child, and still have relatives there. We used to pass through Istanbul in the summertime on our way to visit my grandmother, who lived by the Black Sea, and would then move onto Georgia from there. I have very fond memories of Istanbul; it is a city that has changed so much even since I was a child.

It’s a city that, to me, represents a very transient nature, because it’s a place where different people and religions have moved in and out and therefore the neighbourhoods change. The streets in Crossing where these women live have so many layers of history. For example, in the mid-1800s, it was an aristocratic neighbourhood where the Greek, Byzantine, or Armenian population lived. But then they were kicked out, and the area became populated with Turkish people. A lot of Kurdish people from Eastern Anatolia moved in.

After a while, that area became derelict, and then they built a huge highway through it. It was so weird. I don’t know what happened, but half of it became more affluent, and then the other half less so because of this. That side looks so beautiful.

The area you mentioned, where the trans women live, did you know about that area before making Crossing?

LA: I had passed by there before and found it interesting, but not really. When I started making Crossing, we had a production company in Turkey to help us out, and they contacted these different NGOs. From there, we started doing research. Everything in the film is very research-based, and I also worked with people from that community.

Challenging The Status Quo: Levan Akin On Reclaiming Georgian Culture And Tradition

In terms of Georgia, and specifically via And Then We Danced and Crossing, you are very interested in how traditions shape societies and culture. What are your motivations behind portraying these traditions and what challenges do you face when doing this?

Levan Akin: My motivation is trying to reclaim my tradition and culture that have been hijacked by the right wing, by conservative and religious people. That culture is my culture, it is everyone’s culture. Nobody is allowed to tell me that I can’t be a certain way, or for instance adore Georgian dance!

Growing up gay in an environment that is very hypermasculine, you are made to feel like an outsider. That shouldn’t be the case. This is something I am exploring in my work.

Lia is a great character because she is trapped and guided by those right-wing values. She doesn’t accept Tekla, for example, but slowly changes her views.

L.A.: I don’t know if I would say right wing in a Georgian context. I don’t think she is right wing in that way. I just think that she is also a person who has been conditioned by the patriarchy. You get the sense that she is a woman who, at some point in her life, didn’t want to subjugate herself to a man. That was a decision she made, maybe subconsciously. She isn’t married, she doesn’t have children. Georgia is a country where having children is the most pristine and important thing you can do. Everything is built around the idea of family. It is almost okay to be gay, and for everyone to know you’re gay, as long as you have a woman and children, and then you can live your little gay life on the side.

In that way, Lia, Achi, Tekla, Evrim, and others are victims of the same thing. They are victims of patriarchy and capitalism, which are intertwined. What I really wanted to say was that queer people in families really struggle a lot. Their struggle inadvertently rubs off on women in their families, who start to see their own life in different ways because of the struggles of the queer movement. I think that is beautiful. For Lia, in her quest to redeem herself and her sister, she is like a samurai: she can find Tekla and then she can die. In that journey, she ironically finds a spirit within herself thanks to Tekla’s sacrifice.

Achi and Lia have an intergenerational relationship. How does this relate to Georgian society?

L.A.: In Georgia, there is a great narrative of the post-Soviet generation versus the Soviet generation. The former are growing up with the Internet, they are more globalised, more Western-leaning. In contrast, the Soviet generation are all bigots who basically want to go back to the Soviet Union. But it is much more nuanced than that.

That sort of polarisation just serves the purpose of the oppressor. Crossing was a way to bridge that gap and show people, if we can ever screen the film in Georgia, that, for example, my grandmother and I should be friends. We are the same people. We should stick together, because the only people who benefit from polarisation are the super-wealthy. You need to kick them down.

Is there any chance of Crossing being screened in Georgia?

L.A.: If the sitting government is ousted in October, then maybe. If not, I don’t know. I am getting so many messages from people who want to watch it.

Complex Realism: Levan Akin On Creating The Detailed Character Tapestry Of Crossing

*Spoilers for the ending of the film in the next three questions*

I love the ending, specifically how Lia finally finds Tekla, before you realise that it is just in her imagination. It’s heartbreaking, but very realistic. What made you opt for this ending, as opposed to having her actually find her niece?

Levan Akin: I never wanted them to meet. I’ve always tried to keep my films hopeful, but also to be based on the real world. She could never just find her like that. It would have been stupid, but I still wanted to show the audience what their conversation would be like. Achi asks Lia throughout the film what she would tell Tekla if she saw her again, and Lia pushes it away. She doesn’t want to talk about it. I wanted the audience to hear the words because I feel like a lot of us, especially from that region but also probably from here, never get to have those words with someone that they should have with them.

It was beautiful. When they passed on the bridge, it was a nice moment, but perhaps unrealistic.

L.A.: Yeah, everybody was like, “Oh no, I hope you’re not going to end it like this!”

You have other similar dreamlike moments to this one, such as when Lia is sitting on a bed with her eyes closed, and a hand reaches out to touch hers. What was your thought process behind these moments?

L.A.: I wanted to somehow express Lia’s internal struggle and guilt. I felt like doing that within this more surreal element would be very beautiful and heartbreaking.

*No more spoilers from this point*

You’ve mentioned all these characters, who are all so complex and detailed. What was the writing process like?

L.A.: It was tricky. There are also versions of the script with even more characters! For example, the mother of one of the boys had her own storyline for a while. It was a very rich world that I created, because I spent a lot of time with the script. It was also very tricky to cast the film.

Everybody has to work like they have their own movie. There are essentially three leads, so it was hard. I would like to do a movie specific to Evrim, for example.

Evrim could definitely have her own film. She is an inspirational character who suffers a lot of discrimination, but still makes it her mission to help other people in similar situations. What was the inspiration behind her character?

L.A.: The inspiration was several trans women that I met during my research phase. It was so inspiring to see how they were navigating their environments, and I really wanted to show that in Crossing.

Avoiding Dramatic Pitfalls: Levan Akin On The Earnestness Of Crossing

There is a lot of discrimination in Crossing, but you also have some really beautiful moments and highlight the benefits of people being respectful to others and living harmoniously.

Levan Akin: I didn’t want Crossing to be too negative, but I also didn’t want it to be saccharine. Human beings are capable of being very empathetic and helpful, but we live in very cynical times. I wanted to make a film that felt very earnest, because I feel like there is a fear of earnestness. Everything has to be sarcastic. There is a whole genre within film of embarrassment humour. I am tired of that and I wanted to make something that was opposite to this.

In both And Then We Danced and Crossing, you use dance as a way to protest and express freedom. You do it twice in Crossing. Was it always important to include dancing in Crossing?

L.A.: You can express so much with dance. At the end of Crossing, Lia and Achi have a conversation through dance. She is a little tired and sad because of everything that has happened, whilst he feels guilty because he lied to her. Then they make amends by dancing. That is much more fun than watching two people talk about it. It is a very visual tool. I also love old Italian films, and there is always somebody in them who spontaneously dances or sings!

Thank you for speaking to us today.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Crossing will be released in UK & Irish cinemas, in select US theaters, and in Latin America, Germany, and more countries on July 19, 2024 and will be out globally on MUBI from August 30, 2024.