Frank Herbert’s Dune presents a faithful adaptation of the novel with electrifying cinematography, although is thwarted by aged and unambitious visual effects.

Welcome to Countdown to Dune! In this five-part series, I will be exploring all the onscreen adaptations of Frank Herbert’s epic science fiction novel Dune. Denis Villeneuve’s highly anticipated adaptation was supposed to be released this December, but due to COVID-19, the release date has been pushed to October 2021. With almost a year to go until the new film comes out, now is the perfect time to visit or revisit the Dune films and television miniseries. In this second installment, I will review the 2000 television miniseries Frank Herbert’s Dune to explore how this story benefits from a longer presentation.

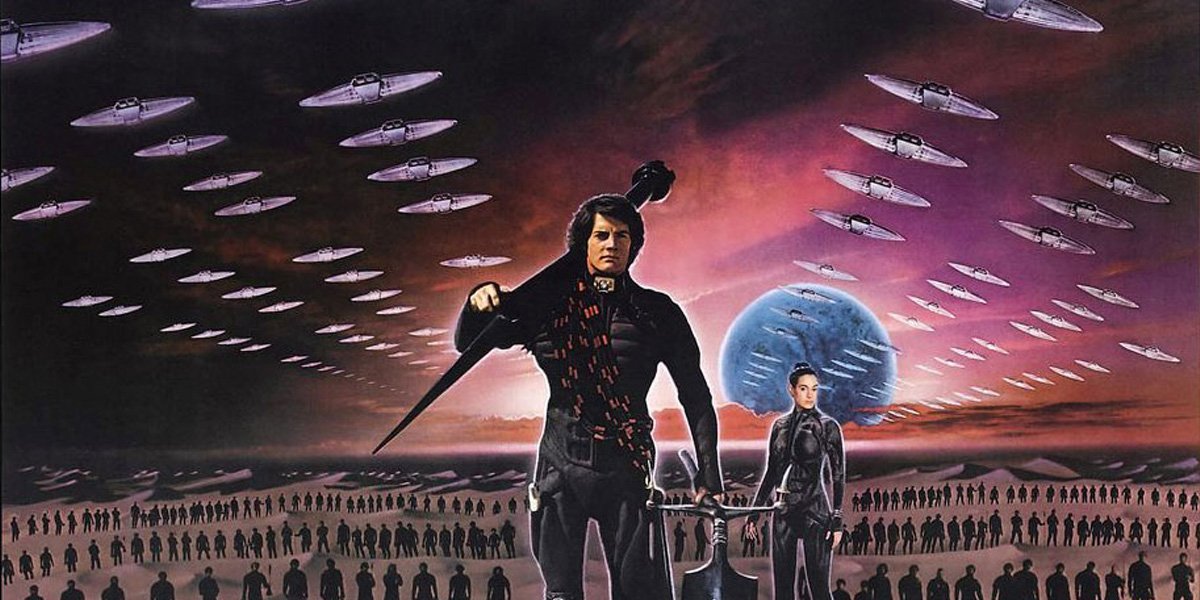

Following the disappointing 1984 David Lynch film, Frank Herbert’s epic novel Dune returned to the screen again in 2000, this time as a television miniseries. Producer Richard P. Rubinstein had had his eyes set on adapting Dune for television, believing that a longer narrative format on the small screen was the perfect medium for an adaptation of such a long and sprawling novel, and production was greenlit as soon as the rights were acquired. Written for the screen, directed by John Harrison and filmed at Barrandov Studios in the Czech Republic on a $20 million budget, Frank Herbert’s Dune premiered on the Sci Fi Channel in December 2000. The miniseries was a groundbreaking television event, shattering viewership records and were among the highest-rated programs on the network at the time. The miniseries later won two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Cinematography and Outstanding Visual Effects, the former far more deserving than the latter, however.

For fans disappointed by the rushed, paltry narrative in Lynch’s film, Frank Herbert’s Dune finally presents a comprehensive and faithful adaptation of the novel. Where the 1984 explained missing gaps in the story with voiceover narration and hasty montage, the miniseries lets the story breathe by showing instead of telling across three episodes, each an hour and a half long. If a little too by the book at times, this longer format explores the political, religious, and mystical elements in detail with organic onscreen worldbuilding that also grants room for the story’s essential environmental implications.

The second episode, taking us on Paul and Lady Jessica’s journey through the sand dunes of Arrakis, establishes the desert dwelling Fremen culture through detailed scenes of their ritual and customs and gives plenty of necessary screentime to the character of Chani, the Fremen woman whom Paul first meets in his dreams and falls in love with. While an extensively faithful adaptation of the novel, Harrison takes a few liberties with the story such as giving Princess Irulan a more active role in the story, a welcome change that adds greater significance to her character than in the novel.

While satisfying in its narrative breadth, the screenplay feels a bit conventional at times, the dialogue seeming a bit unremarkable as it was probably simplified for a general television audience. The quality of the performances varies, ranging from compelling to uninspiring. Portraying the protagonist Paul, Alec Newman begins as a bit aloof in the first episode, yet demonstrates his naivety and curiosity well and by the end of the miniseries, his growth into a political and spiritual leader feels organic. The female roles are all excellent, Saskia Reeves granting Lady Jessica with a noble yet emotional presence, a graceful and cunning Julie Cox as the Princess Irulan, and most notably Barbora Kodetová who gives Chani an earthly, sensitive strength.

Also memorable are a regal Giancarlo Giannini as Emperor Shaddam IV and a gruff yet commanding Uwe Ochsenknecht as the Fremen leader Stilgar. Ian McNiece offers the necessary vile and scheming persona for Baron Harkonnen, although comes off a bit too comical at times (I much prefer the more calculated, grotesque performance from Kenneth McMillan in Lynch’s film). Most disappointing are a soft-spoken William Hurt who fails to capture the noble command of Duke Leto and Matt Keeslar as Feyd-Rautha, who lacks the volatility and vengeful energy that Sting captured so well in Lynch’s film. Outside of these main performances, many of the smaller roles throughout the miniseries feel uninspired with rote dialogue delivery.

Legendary Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, best known for his stunning work on Apocalypse Now and Il conformista (The Conformist), imagines the world of Dune with vibrant visual style, taking inspiration from his unique philosophy of color. The miniseries boasts a dazzling light and color scheme with distinct aesthetic characteristics for each of its different settings, such as baroque golds and indigos for Emperor Shaddam IV’s palace and deep reds and violent angular geometric shapes for House Harkonnen framed in dizzying Dutch angles. Also visually striking is the intense blue glow of Fremen eyes (the effect of spice consumption) in several scenes that adds a unique mystical characteristic to these characters and the fantastical world they inhabit.

The costume designs are equally as colorful and flamboyant, and the physical sets are impressive for a television production. The miniseries was initially going to be filmed in an African desert, but due to uncontrollable weather conditions, the crew decided to shoot on the more easily controlled environment of a soundstage, which appears obvious in scenes set in the desert. While not as convincing as filming on location, the techniques themselves are worth noting—Storaro and his crew experimented with printing blown-up images to use on set as backdrops instead of greenscreen, a precursor to a technique of filming on real-time digital environment displays that was used recently on The Mandalorian.

While there is much to be commended for the miniseries’ practical aesthetic designs, its large-scale sequences of sandworms, battle scenes, and establishing shots of the desert of Arrakis and its city Arrakeen are depicted using atrocious CGI. For a television production in the early 2000s, these effects may have been groundbreaking, but seen through contemporary eyes, they appear terribly aged. Especially contrasted against the physical sets and props, these images resemble shoddy video game graphics and convey none of the visual scope and grandeur necessary for this story. The 1984 film demonstrates much more imaginative and convincing visuals, making one wonder if this miniseries would have benefitted from filming its establishing shots in an actual desert or using practical miniatures and hand-drawn matte-paintings. Unfortunately, the score too disappoints in conveying an adequate sense of scope for this story. Composer Graeme Revell relies on cliched drums and “ethnic” woodwinds for a predictable “desert” sound, and apart from a couple stirring moments like the main theme, his score lacks a memorable and powerful musical identity, especially compared to the more rapturous and grandiose Dune scores from Toto and Brian Tyler.

Overall, Frank Herbert’s Dune is a puzzling, at times frustrating effort. It’s satisfying to see such a faithful adaptation onscreen, yet disheartening to see that the story wasn’t given the proper visual scope and ambition that Dune desperately deserves. A proper adaptation like this would certainly have required an even greater budget and resources, and at the time, short form television series weren’t as prestigious as they are today, so it’s understandable why the miniseries feels conventional and restrained in its approach. Yet while watching this, I couldn’t help but notice that I could feel the emotional urgency and power of the story, especially in the second and third episodes.

Maybe it was my familiarity with the world of Dune and witnessing the complete narrative brought to life onscreen, but I also wonder that it was the story overpowering its material limitations—the ultimate triumph of storytelling over form, where stories themselves contain the power to enlighten, compel, and transcend their medium and resonate on intellectual, emotional, and spiritual levels. It’s difficult to put into words, but it’s something that we feel every time we experience a compelling story, a feeling that’s ingrained within our cultural DNA. This isn’t a perfect adaptation and not as satisfying as it could have been, but it lets the narrative come to life and display that timeless power of story to speak to us in ways beyond conventional means we are familiar with and immerse us into a journey through a strange and fantastical world.

loudandclearreviews.com

loudandclearreviews.com