Flying Images (1989) is an aptly named eleven-minute movie, featuring a stroboscopic combination of the countryside with pictures of a woman.

In a state of complete, melodramatic self-obsession, I admit that I am feeling worried, and that this feeling has its roots in my recent discovery of Nakamura Masanobu’s Flying Images (1989). Because I have no productive use for this worry other than to write about it, I’d be grateful if you allow me to explain. You see, being known as a person who has little personality outside of watching an unhealthy amount of movies means I am semi-regularly asked the question: “what’s your favourite movie?” Due to the frequency in which I am asked this question, I have developed an automatic response that currently reads as such: “I don’t know. I like to think I haven’t seen my favourite movie yet.” I can’t deny that, when spoken aloud, this comes across as a facetious, cop-out of an answer, but it is honest.

I fear that, in devouring movies like chocolate, I will happen to discover that one favourite movie while still young. I shiver to picture myself lying upon a deathbed being asked that same question and my response to it being the name of a movie I saw fifty years earlier. Would my answer then render the last fifty years of movie-watching reasonless? Would it be wasteful for me to continue watching movies if I could now, in my twenties, confidently identify my favourite movie? And so here lies my worry, for in April of 2022 I saw Flying Images (1989) and I was quickly struck by its presentation of everything I fancy in a movie.

Perhaps indicating that I am not as devout a follower of cinema as I appear, I do not struggle to list the aspects that I ‘want’ from a movie (for surely true disciples of an artform as varied and diverse as filmmaking would not have a criteria to apply to each movie-watching experience). In no particular order, and accompanied by filmic examples I have great admiration for, these aspects are as follows. I have a simple preference for movies that capture the countryside. For instance, the home of character Stephen in Accident (1967), the forested hills surrounding the central location of La Ciénaga (2001), and the isolated farmland of The Naked Island (1960).

I also have a fondness for cinematic depictions of intimacy, in all of its dimensions, like the flourishing romance at the heart of Psychobitch (2019), the unbreakable brotherly bond in I Was Born, But… (1932), or even the irreplicable friendships present between the stunts of each Jackass movie. Then, another aspect distilled to a single word (though difficult to define in relation to movies): spectacle. Ethan Hunt leaping out of a place in Mission Impossible: Fallout (2018), Carol Anne being yanked into a puddle in Poltergeist III (1988), or a pink-suited man singing about the minute size of humanity whilst walking through space in Monty Python’s Meaning of Life (1983), for example.

These three words, countryside, intimacy, and spectacle, do of course account for a broad amount of cinematic output and are typically subjective. What I find to be intimate another may find to be impersonal, what I may see as being countryside another may see as being suburban. With this in mind, Flying Images (1989), as according to my own tastes and perspectives, emerges as being the perfect combination of these three aspects. I read this statement, despite it having been typed by my own hands, as being fairly pompous, and almost entirely unfounded. I would never want you to think of me in such a way, and so, with your patience, I will now write more specifically about Flying Images (1989) itself.

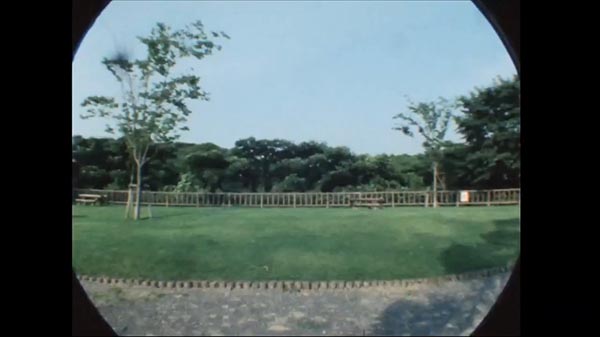

The movie depicts a walk, or a flight, along a woodland trail. The journey begins from a lawn-side pathway, beside a number of picnic tables. The horizon and, consequently, the centre of the frame is occupied by swaying trees, conducted by an unheard wind. Beyond is a hazily cloudless, pale blue sky. The pathway, the camera, and the audience, passes by further lawn-sized swathes of grass, scattered trees, and a telephone mast encompassed by chain link fencing. From here the trail truly begins. It’s a bright, pleasant stroll below a rich, green canopy. A single rope barricade stops approaching foliage from invading upon the trodden soil and wooden steps. The path rises and falls, the trees clear and thicken, a stranger passes by.

I’m embarrassed, attempting to describe the movie in accordance to how it makes me feel, but the woodland images are so familiar to me I can almost smell and hear my own memories in the watching of them. Simultaneous to this countryside stroll, Flying Images (1989) also exhibits a collection of pictures. They are of a woman, captured in a variety of moods and positions. Her legs, her arms, and her torso are (at times) the sole subject of these images. The woman sits with a smile, she slumps with indifference, but is always captured with such affable closeness so as to seem only a breath distant. The comforting proximity of both the forest and the woman were thoroughly enchanting the first time I saw Flying Images (1989), and they have been so again every time since.

I hope you agree then that ‘countryside’ and ‘intimacy’ are easily ticked from my imaginary criteria, whilst I consider if I ever truly understood the capacity in which these words could be applied to movies before having seen Flying Images (1989) – which is likely hyperbole, but I often find that nothing can express emotion quite like exaggeration. This leaves ‘spectacle’. In my movie consumption I have not so far found anything that captivates me more than a film whose object is its own creation (or perception), and especially the stroboscopic effect often utilised by said movies – as Flying Images (1989) does. If this were the 1990s I would be agitating a number of self-labelled transgressive filmmakers for writing such a thing, but I have adored structuralist cinema since my introduction to it. Blazes (1961) by Robert Breer, and 3/60: Bäume im Herbst (1960) by Kurt Kren, for example.

There are also two other things beyond my three fictional tick-boxes that contribute to my love for Flying Images (1989). I will write of these briefly for I suspect they may be a tad controversial. First, I find the movie to be equally effective with the volume down as it is up. Sometimes I’ll mute a movie and put on some music, or listen to the world outside my window, and I find Flying Images (1989) lends itself well to these most blasphemous of practices. Second, and I sincerely hope no cinema police are reading this, the movie has a highly practical portability to it. I can watch Flying Images (1989) on my telly from underneath a blanket, I can watch it on my laptop between writing emails, and I can watch it on my phone while riding a train, though wouldn’t it be miraculous to see it projected?

It has taken me a prolonged amount of time to write what you have so far read, and despite this, I sense to have not yet accurately captured my feelings toward Flying Images (1989). In truth, my feelings have changed throughout this writing. Originally, as I said, I was worried. If my personality relies upon my exploration of cinema, what happens when I feel to have discovered the object of that exploration? Then, I was relieved. Perhaps this means I can stop feeding on movies like a pig with its snout in the trough, and start delicately supping on movies like a practised dinner guest. Excitement closely followed. If Flying Images (1989) is concrete proof of what I enjoy most about movies, perhaps this was an excuse to reappraise all the exploration I have so far done.

Finally, and not a moment too soon I should think, a liberating sense of self-awareness came over my melodramatic, self-obsessed, brain. “Kei,” this sense said, “you understand these are just movies, right? If you want to stop watching so much stuff, simply stop watching so much stuff. If you think your personality is flimsy there are things you can do to strengthen it. I assure you that reality is far more interesting than your daydreams about getting interviewed from a deathbed. Get over yourself.” Being suddenly possessed by a talking sense is, again, total exaggeration, but I stand by its sentiment. I think Flying Images (1989) is my favourite movie, and its power to show me how I’ve been overthinking is certainly one of the many reasons why.