In this interview from the Berlin Film Festival, director Bruce LaBruce tell us what inspires him in Pasolini’s work, how an art project became the Berlinale-premiering The Visitor, and more.

Bruce LaBruce bring The Visitor to the 2024 Berlin Film Festival, where we sat down with the writer-director for an interview about his new film. The movie is a remake of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968), which follows a man who seduces every member of an upper-class family and changes their lives forever. But in the best LaBruce tradition, The Visitor adds so much more to this already fascinating story: drenched in symbolism and filled with provocations, the film uses its titular “alien” (Bishop Black) to send a message about acceptance, liberation, and the power of queer love – and sex – as a means to fight racial hatred.

It’s a purposefully explicit, even pornographic film, where sexual liberation becomes a means to affirm one’s identity in a world driven by hatred. Both a political statement and a transcendent, stunning experience, The Visitor won’t be for everyone, but if you’re a fan of Bruce LaBruce’s work and like his most explicit movies, you’ll definitely find a lot to enjoy here too.

We spoke with Bruce LaBruce about the origins of the film, what inspires him in Pasolini’s work, casting and shooting The Visitor, and more! Read the interview below.

Bruce LaBruce on How His Art Project Became a Berlinale-Premiering Movie

Congratulations for The Visitor‘s Premiere at the Berlin Film Festival! What does it feel like to return to the Berlinale?

Bruce LaBruce: I haven’t shown a film at the Berlinale since 2017. I had two films here that year: one in Forum, called Ulrike’s Brain, and the other in Panorama, The Misandrists. It’s great! I’ve shown a film at the Kino International before, Otto; or, Up with Dead People in 2008: it’s one of my favorite cinemas in the world. It’s so beautiful. We used to have great cinemas like that in Toronto, but they tore them all down, so it was really a pleasure to show the film in a space like that. The sound was just incredible: we put a lot of work into our sound design [Chen Wissotzky and Kieran Simpson], so it was great to hear it in that space, and to have so many people there, watching a porn film.

One of your producers for the film was journalist and filmmaker Victor Fraga, who also co-wrote the script with you and Alex Babboni. How did this collaboration start?

B.L.B.: Yeah, I met Victor and his partner, Alex Babboni, who does Doesn’t Exist Magazine: each issue is dedicated to one artist, and so they did one dedicated to me. I did this fashion art shoot, which was my idea: it was a reimagining of Teorema in a science fiction context. Victor and Alex wanted to bring me to London, and they met this organisation called a/political: they’re the main of producers of the film, in terms of financing.

a/political is a nonprofit that support artists who are rejected by the mainstream art world for whatever reason – artists whose work is too difficult, too political, too controversial, whatever. They represent artists like Andrei Molodkin – there’s an article in the New Yorker about him [“The Artist Holding Valuable art Hostage to Protect Julian Assange“]: he built a furnace, and he’s put Picasso and Warhol’s artwork in it. And if Julian Assange dies in prison, he’s going to burn all this famous art. That’s the kind of artists they represent. Molodkin has a foundry in the south of France and that’s where we shot part of the movie.

So I had two producers: a/political, and Victor and Alex. It was collaborative: Alex and Victor did some writing for the film as well. But in terms of what my vision was, I had no restrictions. It wasn’t like when I make a movie with a bigger budget and get financing from the Canadian government, and they want to have input into what you’re doing. You have screenings for them, and they make suggestions – whether you take them or not – so it’s a more hands on approach, and they want you to make a more commercial kind of project, basically. But with this, it just started out as an art project, and I didn’t even really expect it to become a film that would be shown at the Berlinale and be distributed. So it’s kind of a nice surprise.

The Visitor as a “Sexually Potent” Projection of People’s Paranoia

I read a quote on a/political’s site, where you said, “If you are going to make a film about sexual revolution, it’s best to put your Marxism where your mouth is and make the movie sexually explicit, or even better, pornographic”. And it really is subversive, this idea that it’s a porn movie but it’s also about healing – even more so since it’s a refugee who does the healing.

Bruce LaBruce: You know, this film is kind of a companion piece to L.A. Zombie [2010], which is also a crazy movie about an alien zombie who comes to LA. He finds dead people around the city and he f*cks them back to life, so they are resurrected. It’s kind of a Christ figure in both movies. In L.A. Zombie, it was this idea imposed In the post-AIDS era. I felt like queers – and queer sex – were pathologized, in a way, because of AIDS and “tainted” blood, or HIV blood. Gays became pariahs, and so it was a way of reversing that, and making these characters – the aliens, or visitors – who actually give life with sex rather than create death. In a way, it’s a reversal of that pathology.

At the beginning of The Visitor, I also have all that text that you hear on the voiceover [in the first scene of the movie], which is taken from actual speeches from right wing politicians and pundits. It’s very racist, and they kind of weirdly sexualize the refugees: they talk about their big Black d*cks and say they’re trying to, you know, f*ck their daughters, and all that old fashioned paranoia. So I was trying to reverse that paranoia and also play into it, by making him into this sexually potent figure, which is what people project onto him. But he’s also a Christ-like figure, in a sense.

Bruce LaBruce on What Makes Pasolini so Fascinating

I adored the first scene of the movie! We can hear political speeches like Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” one as the camera pans on the River Thames, till we see a suitcase floating on it, and then, eventually, your “alien” (Bishop Black) emerges from it. The moment that really got to me and I thought was perfect are the church bells we hear when he stands up, but the whole scene is so well-crafted. I love what the sound design is doing too, and also the distorted video playing at various speeds.

Bruce LaBruce: I did a theatre project In Berlin in 2008 [“Cheap Blacky”], where I referenced Pasolini: there was a suitcase pulled out on stage, and one of the characters emerged from it, so I kind of revisited that idea. You know, it’s just meant to be very symbolic about refugees coming to London, and it’s just that feeling of disorientation when he comes out of the suitcase, if you see it from his perspective. I mean, he’s in this alien foreign land, and the Thames is so weird anyway, because it has a sand beach and this weird tide that goes up and down. So it was a way of representing that disorientation and alienation that people feel when they come to a strange land, and it’s a Pasolini film, so of course I put in a lot of religious content. That’s what makes Pasolini so fascinating: he was a gay, Marxist, atheist Catholic – he embodies all those contradictions. The film is about religious transcendence, finally, with the levitation at the end, so I really wanted to make it a religious, queer porn film, which is already a Pasolini dialectic.

What does Pasolini mean to you?

B.L.B.: Pasolini, for me, is one of the great master queer filmmakers, along with Fassbinder. I was a film student in the 80s, so they were two of my great inspirations. I watched all of Pasolini’s films as a kid, and then, when I made the film, I took it very seriously, because he’s the master, and I don’t take it lightly. I really investigated, rewatched the films, read the book “Teorema” that he wrote concurrently with the film… He has a loose trilogy at the end of his life: Porcile, Teorema, and Salò. I put bits of Porcile and Salò in The Visitor as well.

He embodies all those insane contradictions, being a queer, Catholic, atheist Marxist, you know? – which don’t go together. He also has this thing about the working class and the hustlers. I’ve made a lot of movies about hustlers: male prostitutes, misfits, people who don’t fit into society because of their sexuality, or because of their class… And that’s all built into Pasolini films. And then there are the camp aspects. He’s into Medea, played by Maria Callas [in the 1969 film Medea], and these over the top female characters. Silvana Mangano, the mother in Teorema, is a very camp character – think of when she screams in the car – so I wanted to have fun with it as well, and play into the campy aspects of it. With the maid, we made it kind of slapstick. I was trying to be as reverential and true to Pasolini as I could, but also be a bit mischievous and play around with the material, and make a bit of satire about it as well.

Bruce LaBruce on the Casting Process and the Visuals in The Visitor

Every single one of your actors is so unique and memorable. What was the casting process like?

Bruce LaBruce: When I make a film like Gerontophilia [2013], or Saint-Narcisse, it’s done in a more conventional, industry way: I use a casting agent and audition professional actors. But with films like The Visitor and L.A. Zombie, or perhaps my earlier films like The Raspberry Reich [2004], it’s more about using non actors – sometimes porn actors – and it’s through word of mouth, or maybe I put a notice on social media that I’m looking for performers. Victor and Alex also suggested a number of performers for each role. And I was in Toronto, so I only talked to a couple of them on Zoom: they sent me videos of them, and that’s how I cast them.

But I didn’t meet any of the members of the cast until the first day of shooting on set, except for Bishop Black, who plays the visitor: I’ve worked with him before. I made a porn film with him, photographed him, and also made a music video with him, so we had a history, but I had never met the rest before. Only Bishop and the mother, Amy Kingsmill, had done porn before. The other four hadn’t, so it was quite amazing. Something magical happened. I wanted a non-binary character, and Ray [Filar] is this amazing, transmasculine woman. And in fact, Ray, who plays the daughter, in real life is actually older than the actor who plays her mother [Kingsmill]! [laughs]

I love the look of the film! I love the color palette that you use, for the writing that occasionally pops up on the screen in between various shots, and particularly the second part of the film is so beautiful.

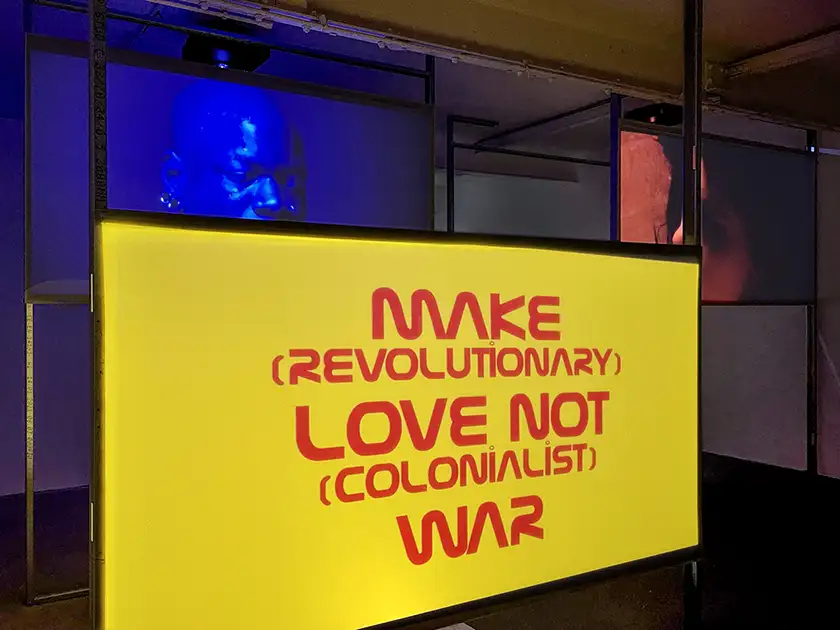

B.L.B.: We shot the first half in London: we did seven full days of shooting, like 14-16 hours a day. We had some really great locations: the house where we shot it was very spectacular – I can’t really disclose whose house it is! [laughs] – but that was fun. The three main colours – yellow, red and brown – are piss, blood, and sh*t [this is a reference to very symbolic scene of the film, right after the visitor arrives at the house], and we played with that colour palette.

I missed some scenes that were very difficult to shoot, especially the liberation scenes at the end: either I didn’t have time to do it, or we couldn’t find the proper locations. So Becky [Haghpanah-Shirwan], the Director at a/political, told me about this compound in the south of France that they have: Andrei Molodkin’s Foundry. It’s a huge set of buildings that he has that are a former foundry: it’s where he makes his art. In the film, those big sculptures that say “capitalism” and “democracy,” that the naked father’s walking through: those art pieces are by Andrei Molodkin.

So we went down there: it’s in the Pyrenees, in the mountains, which is so beautiful. There’s the waterfall, and also, it’s near Lourdes, the religious Mecca: we got a permit to shoot in Lourdes. When the maid is praying on her knees, and there’s this enormous church: that’s Lourdes. We weren’t even supposed to shoot in that particular location, but we we used a long telephoto lens so that we could shoot her, and that really saved the film. That spectacular scene with the levitation was also shot in the south of France, in this beautiful location.

Thank you for speaking to us!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

The Visitor had its World Premiere at the 2024 Berlin Film Festival and will have its UK premiere on January 11, 2025 at an undisclosed location in London: tickets via Vice. . Read our review of The Visitor below!