With no end in sight to the coronavirus pandemic, now is the time to dabble in the world of arthouse cinema.

Since its rise to popularity in the 1960s and 70s, arthouse cinema has gained a reputation for being equal parts pretentious and inspired. With the international attention given to filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman and Jean-Luc Goddard by both critics and film festivals, mainstream audiences gradually became aware that there was more to cinema than big-budget biblical epics or melodramatic literary adaptations. During this period, films such as The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy) and 8 ½ (Federico Fellini) gained praise outside their intended audience, had a large cultural impact, both in spite of and due to their unique artistic execution, and have become classics in the decades after their initial release.

Sadly, the 1980s ushered in the rise of what would become the modern blockbuster, and, as a result, arthouse cinema lost the wider audience it had enjoyed previously. Filmmakers still made the art they felt compelled to make but received much less attention than had previously been given. Today, arthouse cinema is more accessible than ever, with streaming services such as The Criterion Channel, HBO Max, and Kanopy boasting a large selection of titles that were previously unavailable. If you’ve always wanted to explore the (often intimidating) world of arthouse cinema, here are seven films to introduce you to the style, ordered from most to least accessible.

7. ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND

(2004, MICHAEL GONDRY)

By 2004, Charlie Kaufman had established himself as one of the chief surrealist screenwriters in Hollywood with Being John Malkovich and Adaptation. His scripts follow a number of arthouse techniques, such as metafiction elements that call out the films’ artificiality and subjective storytelling that often has characters quite literally exploring their own minds. With Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Kaufman, along with director Michael Gondry, took his arthouse influences and applied them to the romantic comedy genre, giving the film a wide appeal while making a number of distinct artistic choices that set it apart from other films in the genre.

Following Joel (Jim Carrey) as he undergoes a procedure to erase the memory of his ex-girlfriend (Kate Winslet), the films spend a majority of its runtime inside Joel’s memories of the relationship as they twist, modify, and ultimately collapse, leaving Joel to wonder if living without the memory is worse than surviving with the pain that a broken partnership brings. While not firmly an arthouse film, it has many of the characteristics of one and is a good introduction to the style of filmmaking.

6. WILD STRAWBERRIES

(1957, INGMAR BERGMAN)

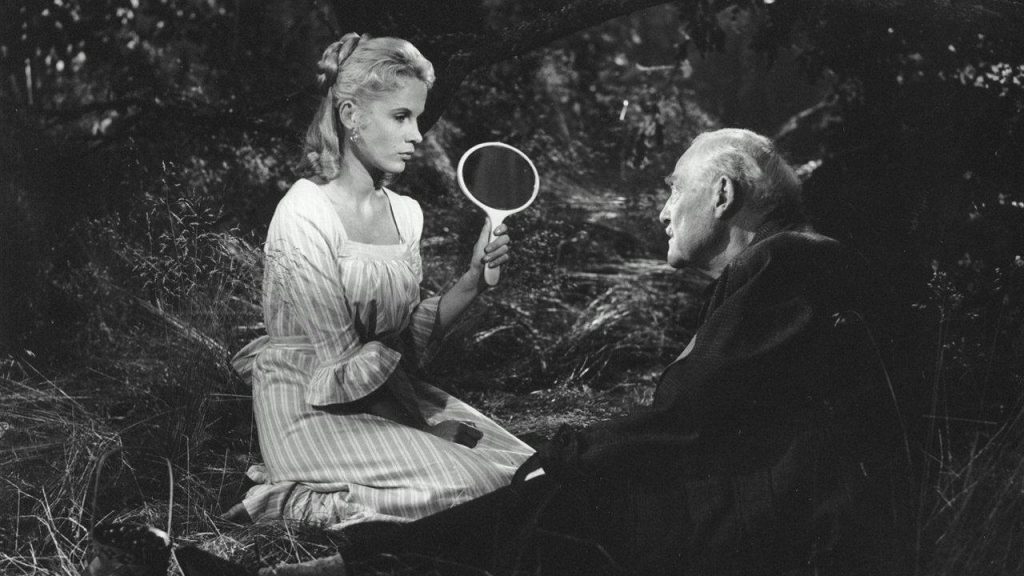

It would be impossible to make any list on arthouse cinema without including at least one film by Ingmar Bergman, who made multiple masterpieces over a 30-year career. While his other works such as Persona, The Seventh Seal, and Through a Glass Darkly may be regarded as better films, Wild Strawberries is a perfect gateway to his filmography and to the style of arthouse cinema that populated the 1950s and 60s. The film follows an elderly professor (Victor Sjöström, whose silent film The Phantom Carriage deserves a mention) as he travels with his daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin) to accept an honorary degree. Along the way, he visits locations from his childhood and meets a wide range of characters, all of which force him to reflect on his life choices.

As with all Bergman films, there is a heavy focus on character development and not much in the way of plot, which often feels slow or meandering to the average viewer. But at a brisk 90 minutes and with a digestible narrative, Wild Strawberries is a great film that holds artistic merit and mass appeal.

5. ANNIHILATION

(2018, ALEX GARLAND)

Genre films are a great way for arthouse filmmakers to express their ideas, because they give them a set of expected plot elements and character archetypes to work with. Most famously, 2001: A Space Odyssey used a killer robot, space travel, and a mysterious monolith to explore ideas such as the nature of humanity and evolution. In Annihilation, writer/director Alex Garland took Jeff VanderMeer’s ethereal sci-fi odyssey and adapted it into a stunning work of genre and one of the most perplexing films in recent memory.

Following a group of scientists (Natalie Portman, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodrigues, and Tessa Thompson) as they traverse their way through a mysterious area known as “The Shimmer”, Annihilation’s plot quickly becomes incomprehensible and new dangers and plot twists appear in every scene, climaxing in a terrifying fight between Portman’s character and, well, we don’t know what it is and neither do the characters. While the plot of Annihilation will certainly turn off some viewers, the persistent metaphors and symbols that appear throughout give the film a rock-solid thematic base that results in a movie made to be picked apart and analyzed rather than passively observed, something all arthouse films require.

4. THE TREE OF LIFE

(2011, TERRENCE MALICK)

If there is one thing that can be definitively said about arthouse films, it’s that those who gain immediate popularity upon their release will be met with a divided response both from critics and film fans. So was the case with Terrence Malick’s 2011 magnum opus The Tree of Life, which won the prestigious Palme d’Or and garnered three Oscar nominations including best picture. Focusing on a fictionalized version of Malick as a child, The Tree of Life follows young Jack as the opposed wills of his parents (Jessica Chastain and Brad Pitt) cause turmoil in his life. The style of the film is dreamlike and cuts between the present and past. It even includes a 20-minute segment chronicling the formation of the universe and the extinction of the dinosaurs.

While on the surface those scenes may feel nonsensical and useless, when applied to the overall themes present in the work (such as the battle between good and evil and the inherent nature of humanity) they elevate the rest of the film and give it a deeper meaning. Like most arthouse cinema, the plot is relatively light, but the characterization and themes pay off greatly to an attentive viewer.

3. ERASERHEAD

(1977, DAVID LYNCH)

No list of art cinema would be complete without one of the works of David Lynch, whose movies are famously bizarre and perplexing, a fact heightened by his refusal to discuss or explain the nature of each of his films. His debut feature Eraserhead openly defies all attempts at description. A young man named Henry (Jack Nance) gets his girlfriend (Charloette Stewart) pregnant and the new couple moves into a cramped apartment near a manufacturing plant. From there, Lynch throws all concepts of plot out the window, filling the runtime with bizarre and often nightmarish imagery (such as the famous radiator lady and the baby the couple produces) accompanied by a distinct urban soundscape that burrows into your mind and refuses to leave.

Described by Lynch as his most spiritual film, numerous interpretations have arisen, such as the film being an allegory for the fears of parenthood or simply a depiction of purgatory. But perhaps Eraserhead is best experienced simply as a weird movie, perfect for midnight screenings and Halloween marathons.

2. JEANNE DIELMAN, 23, QUAI DU COMMERCE 1080 BRUXELLES

(1975, CHANTAL AKERMAN)

Arthouse films often gain a reputation for being overly long with little substance to them, resulting in a wasted viewing experience. While both long and boring in the conventional sense, Chantal Akerman’s feminist masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles is anything but boring. Best known for its simple premise, three days in the life of a mother as she cooks, cleans, shops, and engages in sex work, Jeanne Dielman never loses your attention for a second, constructing a carefully crafted routine for Jeanne (Delphine Seyrig) that slowly crumbles with each minor inconvenience, climaxing (quite literally) in a shocking finale that sits with The Godfather and Inception as one of the best movie endings. In the years since its release, the film has stood as a shining example for communicating complex ideas with very little in the way of filmmaking, instead treating the audience as intelligent and trusting them to glean the deeper meaning. A staple in arthouse cinema.

1. MIRROR (ZERKALO)

(1975, ANDREI TARKOVSKY)

Finally, we reach the end of the list with one of the most difficult films from one of cinema’s most difficult directors. The films of Andrei Tarkovsky have been heralded as some of the crowning achievements of the cinematic art form since their release, but generally have received very little mainstream attention due to their long running times and often inaccessible storytelling choices. Nowhere is this more evident than in his 4th feature film Mirror, which serves as a semi-autobiography both for himself and for the Soviet Union. With a lack of focus on plot and zero memorable characters, Mirror instead seeks to engage its viewer on an instinctual level, as we are presented with vignettes of childhood, warfare, industry, and love that vaguely connect together to create the life experiences of both the protagonist Alexei and the director. It demands the viewer’s full attention, but, if given, can result in a satisfying viewing experience sure to evoke strong emotions.

MORE ARTHOUSE CINEMA

While this list of seven films should serve as a suitable jumping off point for arthouse film, there are countless other directors and movies with impacts and legacies that deserve to be recognized. Below is a list of art films that deserve recognition.

- The Face of Another (1966; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

- The Three Colors Trilogy (1993-1994; Krzysztof Kieślowski)

- Roma (2018; Alfonso Cuarón)

- Rashomon (1950; Akira Kurosawa)

- Sátántangó (1994; Bella Tarr)

- Frances Ha (2012; Noah Baumbach)