After Yang sees writer/director/editor Kogonada present a singularly uncanny examination of human connections, memory, and the need to preserve them.

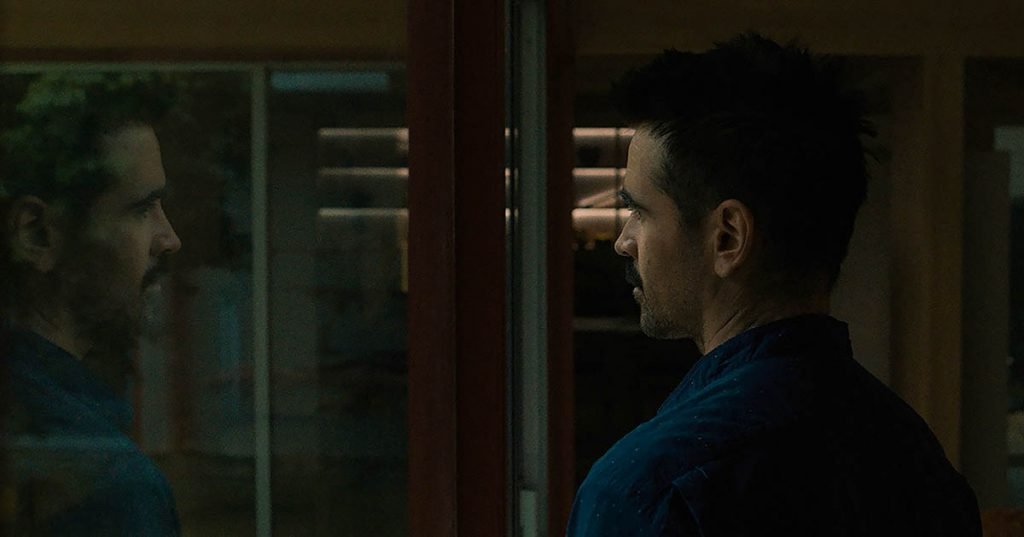

After Yang is an A24 science-fiction film that was given a limited release this weekend in theaters and on Showtime. Written, directed, and edited by Kogonada, the film stars Colin Farrell and Jodie Turner-Smith as married couple Jake and Kyra, whose android son Yang (Justin H. Min) malfunctions and shuts down. This prompts Jake to seek out a way to repair him, which brings him across Yang’s memory banks that reveal a life Jake never knew Yang had led. This causes him to reflect on his own life, including his strained relationship with his wife, his young, adopted Chinese daughter Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja), and a mysterious girl at the center of Yang’s memories (Haley Lu Richardson).

After Yang is one of those movies where, outside of the acting, everything is at least a little bit uncanny. The dialogue, editing, Benjamin Loeb’s cinematography, and even how some of the story progresses, all have unnatural, somewhat artificial tinges to them. But in a majority of cases, this works to the film’s advantage, mainly because After Yang is about a family trying to wade through the emotional separation that has plagued them. A majority of the interactions between Jake and Kyra are distant at best, with both of the two seeming to be on different wavelengths in terms of their connection to one another and what they want from each other.

Factors such as commitments to work, money, and even different backgrounds have driven a wedge between them, and their stiff, witless dialogue and performances reflect that. Even when looking at their surroundings, they regularly come across people who treat Yang’s life and memories like either nothing more than products to be bought and sold, or artifacts to be displayed to a mass public that would likely never understand the sentiment behind such a life, even an artificial one.

A lot of wider shots are used for conversations that would typically be shot more closely to the characters, and a lot of exchanges have the frame locked down and obscuring one of the characters for an extended amount of time, representing the isolation everyone feels even when they’re in the same room. The lighting gives every shot a very hazy, overly glossy tint, creating a sterile look that matches how inhuman most of the interactions feel. And, most bizarrely of all, flashback sequences have many instances of dialogue being echoed before or after a character actually says the words, and sometimes we’ll see the same line being uttered twice from different camera angles.

While I’m not at all sure why those last choices in particular were made – my best guess is that they’re to emphasize the weight of the words in the minds of those remembering them – the other unusual techniques seem designed to remove some of the intimacy that would be found with more conventional filmmaking. This works far more often than it doesn’t, only acting as a detriment to the film during scenes that do need to be more intimate for where the story is going, when connections and personal memories are being restored.

Even then, though, After Yang elicits a strong emotional response thanks to the surreal nature through which we learn about Yang’s past. On top of the lovely visuals used to illustrate his memory banks, the very clever choice is made to have him only able to store a few seconds of memories per day. This means that we get to see the moments in time, the images, and the bits of conversations that Yang found the most memorable … and, by extension, the ones that were most important to him. And indeed, what we see does paint a very beautiful picture of the life he lived. When I look back on a lot of good times I’ve had over the years, I often do just recall simple imagery and atmosphere that doesn’t have a ton of meaning on the surface, like something as simple as looking out in a field. Clearly, Yang felt similarly, whether he realized it or not, and that same sentiment is reawakened in the “real” human characters who have forgotten that.

But with this also comes the reveal of much more personal details that also carry a lot of weight, despite how little of the past we really see. That’s where Haley Lu Richardson’s performance gets to stand out as the best in the film, as she expresses her character’s pain and vulnerability over what she’s been through and seeing the lifeless Yang. That’s not to take away any credit from Colin Farrell or Jodie Turner-Smith, who both give very fittingly subdued, subtle performances. I couldn’t get into Malea Em

ma Tjandrawidjaja’s acting, sadly, but it feels wrong to harp on that given her age. And besides, you still sympathize with her as arguably feeling the biggest sense of loss in her family, given how Yang gave her a sense of belonging despite her adopted background. He was “built” as a Chinese person to help Mika understand her heritage, and now that he’s gone, her parents need to come to terms with their lack of involvement in navigating her through that.

After Yang has a wavelength that’s potentially difficult for the viewer to get in sync with, and its style occasionally gets in the way of what could have been an even more direct impact. But the film’s understated, nuanced ambitions are otherwise fully realized, and Kogonada has taken a very unconventional, bold approach to his examination of holding on to fading humanity. I was taken by this quiet, meditative work of science fiction, and I think most viewers should be able to appreciate it on any number of levels.

After Yang is now available to watch on digital and on demand.