A City Called Macau reduces complex economic and social forces at play in the giant casino industry of Macau to a lazy morality play.

I should start this review by acknowledging my ignorance – I had known neither the scope of Macau’s gambling industry (nine times greater than Las Vegas at peak in 2012, according to a text wall at the start of the film), nor of its prodigious fall since the implementation of anti-corruption regulations in 2014. A City Called Macau tells the story of a “casino broker,” something like a bookie that serves as an intermediary for wealthy clients and the casinos. Functionally, the job exists to allow the wealthy to conceal how much they are winning and losing at the tables. There is real potential for an interesting story about the rise and fall of a gambling empire through the lends of a foot soldier – the sort of thing I could imagine Martin Scorsese bringing vibrantly to life – but this is not the film to tell that story.

A City Called Macau has no interest in the sort of moral ambiguity a better filmmaker might bring to the story. This is the sort of film where, after just three rounds of baccarat, a non-gambler devolves into a deviant addict. His eyes take on a desperate glint, his movements become jittery, his patience evaporates, and he begins barking at any distraction that dare enter his orbit. Just a few hands sees his life destined for ruin. Another scene depicts a player shove his pregnant girlfriend to the ground and kick her repeatedly for “ruining his luck” on a hand. To A City Called Macau, a round of blackjack equates to a heroin needle. It is the Reefer Madness of gambling.

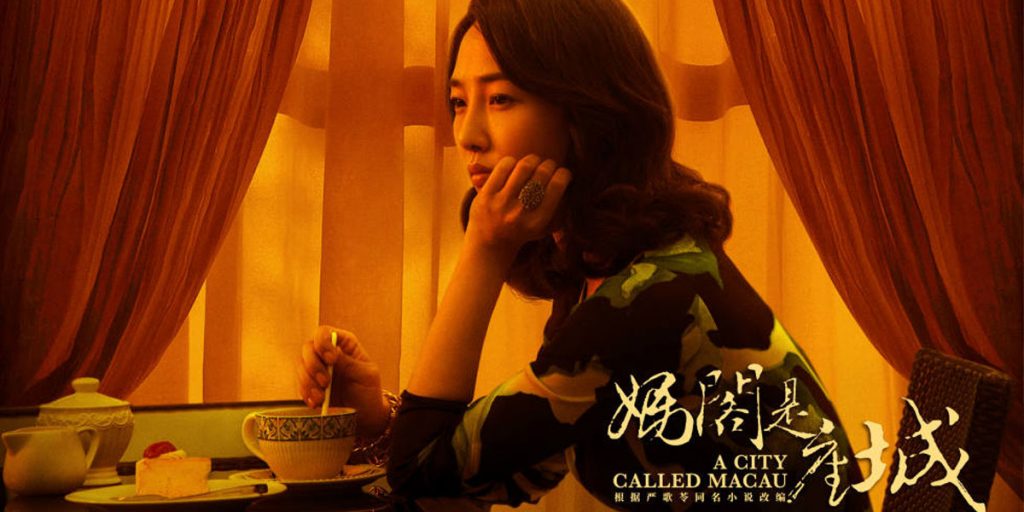

It is worth noting that the lead actress, Bai Baihe (Monster Hunt), is one of China’s biggest stars. She has been a two-time Golden Rooster Nominee (the rough equivalent of a Golden Globe) and her films have seen immense box office success in mainland China. It is her presence in the role that makes clear what is happening here – the film is basically a propaganda piece. The simple reality is that all of China’s films must be approved by the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Accordingly, in order to achieve domestic release, films must meet certain moralistic and loyalist standards in order to open in a theater. A City Called Macau sees China’s most successful female director paired with one of its biggest stars in an award-bait movie. We should not be surprised that it “highlights” the sort of moral values the Chinese government would like to instill in its citizens. It is the sort of film that sees a character’s lighting of a bathtub full of money on fire as a heroic climax and the spiritual cleansing of the cash’s corrupting influence. Textbook communist propaganda.

Bai Baihe is not without talent. She gamely takes on a challenging role, but nobody could possibly make this work. The character is ruined by a bizarre take on the Madonna-whore complex: she must be able to entice men to work with her and serve as a credible enforcer to collect debts, while simultaneously maintaining her sexual purity and remaining entirely oblivious to the obvious duplicity of her clientele. It is an impossible mash-up of the traits required for a successful casino broker and for a character who serves as a moralistic propaganda figurehead. It is a clear example of film messaging overtaking credible character motivation.

That said, the film is well lensed. My two-year-old son was in the room with me for some of the film and remarked “Oh! Me like this shot!” at one particularly lovely outdoor sequence. Some remarkably poor production values in the film’s modest and infrequent action sequences aside, A City Called Macau is a handsome piece. The rest of the cast is largely adequate, but not one is able to elevate archetypical characters into something more. An interesting historical moment wasted by a moralizing, propagandistic story.

A City Called Macau premiered on YouTube on 6th June, as part of the We Are One Film Festival.