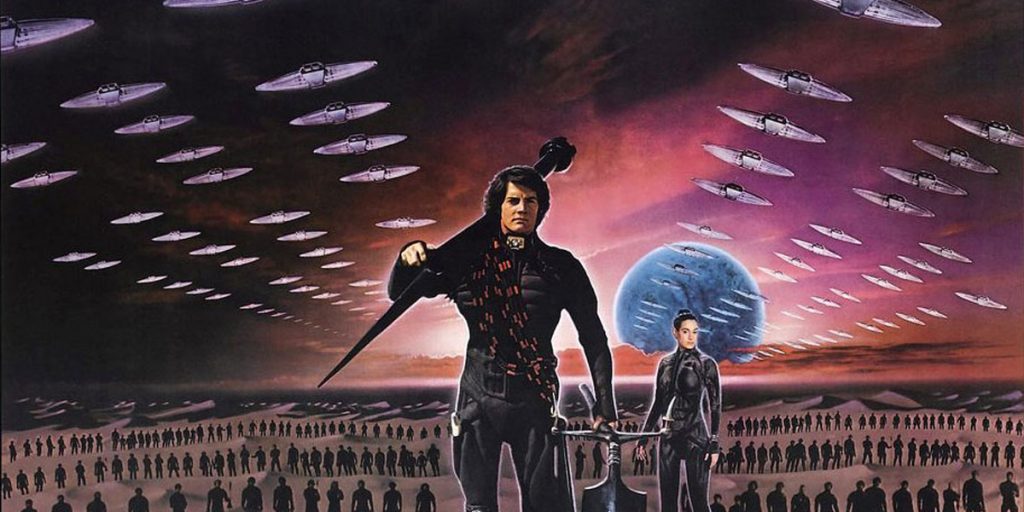

David Lynch’s 1984 Dune adaptation brings the novel to life in strange and mystical vision but fails to match its complex narrative and thematic scope.

Welcome to Countdown to Dune! In this five-part series, I will be exploring all the onscreen adaptations of Frank Herbert’s epic science fiction novel Dune. Denis Villeneuve’s highly anticipated adaptation was supposed to be released this December, but due to COVID-19, the release date has been pushed to October 2021. With almost a year to go until the new film comes out, now is the perfect time to visit or revisit the Dune films and television miniseries. In this first installment, I will review David Lynch’s 1984 Dune film and explore its flaws and its merits.

Frequently regarded as the greatest science fiction novel of all time, Dune is a legendary masterpiece of genre literature with a thematic core as plentiful as its page count. Frank Herbert’s 1965 epic novel takes place in a far future where warring factions of noble houses scheme and battle for control of the spice melange, a mind-bending drug with clairvoyant abilities used for space navigation. The spice is only found on the harsh desert world of Arrakis—known as “Dune”—where House Atreides has just been transferred by the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV to oversee the mining operations. Following the murder of Duke Leto, the noble ruler of House Atreides, his son Paul and his mother Lady Jessica flee into the desert, leading Paul on a transformational quest to becoming a messiah to Arrakis’ inhabitants, the Fremen. Dune is many things: a coming-of-age story, a political thriller with scheming palace intrigue and assassinations, a work of environmental fiction, and a religious allegory with allusions to Christian, Islamic, and Buddhist faiths. Herbert’s dense novel features some of the genre’s most creative world building and elaborate storytelling, eventually launching a major franchise of sequel and prequel novels, games, and film and television adaptations.

Making a feature film adaptation of Dune is no easy task: a proper adaptation clearly deserves groundbreaking special effects and fantastical production design to imagine Herbert’s vision of the far future, but most importantly would require a screenplay to do the intricate story justice. A comprehensive adaption would be nearly impossible—much of the novel is told through internal monologues that immerse us into the scheming minds and spiritual experiences of the characters in ways that could never properly be translated to the screen. And with a book pushing 700 pages, the entire narrative could never fit into the traditional feature film format, as a story of this immense scale and thematic depth would require much more than a two-hour runtime.

After years of failed efforts, the ambitious task of directing a cinematic adaptation of Dune eventually found its way into the hands of David Lynch, who had just turned down an offer to direct Star Wars: Episode VI—Return of the Jedi. Lynch was an unlikely choice for a big-budget studio film and science fiction epic like Star Wars or Dune, a cinematic rebel and outsider whose previous films were the 1977 surreal masterpiece Eraserhead and the 1980 historical drama The Elephant Man. Nonetheless, Lynch carried the film to completion, yet was deeply unsatisfied with the experience, citing studio interference compromising his artistic vision, and has since disowned the film. As for the film itself? A mixed bag with some merits and plenty of crucial flaws.

A conventional and commercially viable adaptation of Dune like this was clearly doomed from the start. The film’s scant 137-minute runtime is deeply troubling, the gargantuan novel condensed into a rushed story that loses the narrative depth and power of the source material. The first act of the film feels especially clunky, devoting too much time to early events that take place in only the first hundred pages of the novel, leading to an unbalanced narrative throughout with inconsistent pacing. Meanwhile, the audience is bombarded with hasty lines of exposition and narration, and viewers who haven’t read the novel will most likely be confused by these quick explanations, while diehard Dune fans will be annoyed by the inorganic worldbuilding of this short cinematic trip to Arrakis. Particularly revealing is that, during the film’s original release, a nervous studio decided to distribute lobby cards with vocabulary from the film to confused theatergoers—it’s never a good sign if your film needs supplemental materials to explain to the audience what they’re supposed to be seeing up on screen.

Major characters like Chani (Sean Young), Paul’s (Kyle MacLachlan)’s love interest whom he first encounters in dreamlike visions, are given barely minutes of screentime, as many subplots of the novel are ignored in favor of an expedited and digestible story. The film assembles an impressive cast with names like Patrick Stewart, Max von Sydow, Sting, Silvana Mangano, Jürgen Prochnow, Brad Dourif, Virginia Madsen, and regular Lynch collaborators Jack Nance and Dean Stockwell, but their talents are used sparingly with such brief onscreen appearances. At times, we hear voiceovers of inner monologues from various characters throughout the film, which feel awkward and distracting despite their best intentions to capture the internal psychological narratives from the novel. Perhaps they might work better if the film captured the same sense of scale as the novel, but these fail to work effectively in the story’s condensed and “audience-friendly” cinematic form.

Despite its narrative inadequacies, Lynch’s film succeeds with its cinematic artistry and vision. He imagines the world of Dune with a twisted and nightmarish vision, capturing the unconventional and even archaic aesthetic the source material evokes, especially in its gilded, regal design. Dune is a weird novel—it’s not set in a sleek high-tech future the science fiction genre is so often known for a world. This is a world with no computers (they were all destroyed following a human rebellion against intelligent machines), where grotesque mutated beings known as Navigators “fold space” for travel across the galaxy and where the elite sisterhood known as the Bene Gesserit practice superhuman abilities and genetically engineer bloodlines to create a superbeing known as the “Kwisatz Haderach.”

A scene where Paul takes a Gom Jabbar test (a pain test to determine if a person is human) bristles with unnerving tension, while a later scene introduces us to the freakish villain Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) as he wickedly laughs and floats to the ceiling in a powered suit, both moments uncomfortable and undeniably Lynchian. Lynch’s signature surreal style and fascination with dreams lends itself well to Dune, a story entrenched in a spiritual and mystical dimension, respecting the source material in this regard. In addition to Lynch’s dreamlike and mind-bending visuals, Toto’s score haunts with Brian Eno’s atmospheric “Prophecy Theme” while a memorable four-note main theme stirs with rapturous energy.

Ultimately, fans of the novel will be let down by Lynch’s adaptation for failing to capture the proper narrative and thematic scope that Dune deserves and new viewers will be lost in the rushed narrative, more confused than entranced by this strange and fantastical world. It’s disappointing for sure, but not surprising considering that a proper film adaptation of Dune would be impossible to produce in the studio system for a mainstream audience. But, if you’re willing to put aside these deep flaws and appreciate the film for what it is—a brutal, terrifying, and mystical vision of the novel with more visual and tonal imagination than you might expect for a studio film of the era, you just might be surprised.

Read the second article in the Countdown to Dune series: Frank Herbert’s Dune (2000): The Triumph of Story