Park Chan-wook’s The Vengeance Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, Lady Vengeance) proves revenge is a lot more than a dish best served cold.

This article contains spoilers for The Vengeance Trilogy (Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy, and Lady Vengeance).

South Korean filmmaker Park Chan-wook’s infamous Vengeance Trilogy is not simply a depraved descent into the shadows of the vengeful human psyche, one fueled by the unquenchable desire for justice. Nor is it merely tales chronicling wronged individuals transforming into blind beasts hellbent on the annihilation of worthy adversaries. At the heart of The Vengeance Trilogy there’s much more at play, because Park Chan-wook’s three films present tales of biblical proportions, carefully traversing the many layers of revenge with an efficacy and precision unmatched by fellow contemporary filmmakers. However, before we explore the ways in which Park Chan-wook elevates the classic revenge narrative by exploring their inherent duality, it’s important to first contextualize both the director’s style and the type of film Park Chan-wook is modifying.

I’m sure we all are familiar with revenge films. We follow our protagonist, who either was wronged in the past or is dealt some major injustice in the first act, and the rest of the film is devoted to them seeking justice. Whether this be an elaborate and highly intricate revenge plan executed to perfection or an all-out guns blazing assault, these stories, at least in my opinion, have grown quite stale over time. While there have been exceptions that utilized their unique style, set pieces, or characters to reinvigorate the narrative (like John Wick or Kill Bill), I’d argue the formulaic revenge tale has remained shockingly intact and undisturbed for a long time.

While some filmmakers may have one film or one scene that provide an interesting or nuanced digression from this formula, only one filmmaker made three entire films dedicated to abandoning this template and truly investigating the moral complexity and intricate duplexity of revenge: Park Chan-wook in his Vengeance Trilogy. Park Chan-wook’s three films in The Vengeance Trilogy are deeply troubling, in perhaps the best ways possible. They are soul draining journeys into the taboo, into the unspeakable violence, perversion, and depravity that reside in the darkest crevices of society. With muted colors, grimy set design, nauseatingly violent set pieces, and an utter lack of regard for the stomachs of the audience, Park Chan-wook’s visual style is that of visceral obscenity. However, there’s a single thread that runs through each of the three installments in The Vengeance Trilogy that cements their spot as being among the most inventive revenge stories ever put to screen: duality.

SYMPATHY FOR MR. VENGEANCE

(2002)

“I know you’re a good guy… but you know why I have to kill you…”

Following the success of his third directorial effort in 2000 titled Joint Security Area, Park Chan-wook released what would be the first segment of The Vengeance Trilogy, titled Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. The film follows Ryu (Shin Ha-kyun), a deaf factory worker, who after being scammed by Black Market Organ dealers and failing to pay for compatible kidneys suitable for his dying sister, agrees to kidnap the daughter of a wealthy business executive, Yu-sun (Bo-bae Han), with the help of his anarchist girlfriend, Yeong-mi (Bae Doona). This sets off a tragic chain of events, first resulting in the death of Ryu’s sister, who after finding out the little girl was kidnapped in order to save her life, elects to commit suicide as to not be a burden to Ryu any longer. While Ryu and Yeong-mi initially have zero intention of killing Yu-sun, things get further complicated when she accidentally drowns as the deaf Ryu is burying his sister nearby. Following this, Ryu goes on a bloodlust hunt, tracking down and killing the people that originally stole his kidney, while Dong-jin (Kang-ho Song), the father of the now deceased Yu-sun, goes on his own destructive path of vengeance against Ryu and Yeong-mi.

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is the first film in The Vengeance Trilogy, so Park Chan-wook spares no time establishing his idiosyncratic style. On its most simplistic and unsophisticated levels, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is three overlapping revenge stories, where the often-clear line of morality is so irrevocably obscured, and the idea of dual perspective is championed above a singular narration. The first revenge plot is introduced within the first few minutes of the film, and concerns Ryu seeking justice against the Black-Market Organ dealers who ran off with his kidney and robbed him of saving his sister’s life. This plotline crescendos into a gruesome altercation involving a baseball bat, necrophilia, and Ryu receiving a near fatal wound.

The second story of revenge we are introduced to seems like the most central to the narrative and follows Dong-jin as he first electrocutes Yeong-mi to death, who warns him her murder will not go unpunished. Disregarding this, Dong-jin locates and captures the injured Ryu. After taking Ryu to the same body of water where his daughter was killed and informing the deaf man that “I know you’re a good guy… but you know why I have to kill you…”, Dong-jin severs Ryu’s Achilles tendon underwater, and watches as the kidnapper slowly bleeds out and dies. After this seemingly all-encompassing climax, we are introduced to the final revenge story, that of Yeong-mi’s allies coming to avenge her death by stabbing Dong-jin and letting him bleed out.

In Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Park Chan-wook doesn’t present the idea of revenge as a linear process with a definitive ending or protagonist and antagonist. Instead, he presents it as an everlasting web of cause and effect, as a series of decisions that often collapse in on themselves and result in the damnation of all involved. It’s sloppy, unmethodical, a never-ending chain of brutality fueled by man’s need for justice and finality. This is the duality Chan-wook presents in the first film of The Vengeance Trilogy: the duality of seeking revenge, as every vengeful act is composed of two elements: action and reaction, sin and punishment, or most interestingly, revenge and later, more revenge.

OLDBOY

(2003)

“Laugh and the world laughs with you. Weep, and you weep alone.”

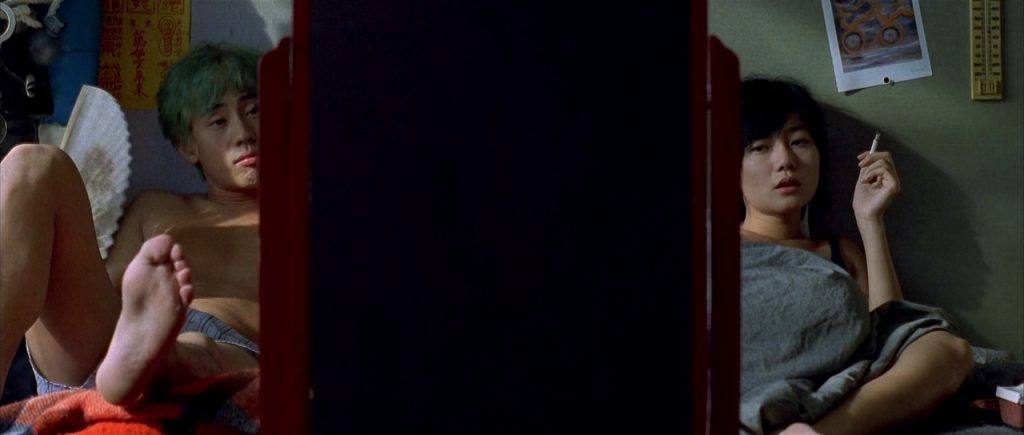

While Park Chan-wook’s Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance got little to no recognition in North America and received some rather negative feedback from critics outside South Korea, it set the tone for his next project, one that would thrust itself into the mainstream and give Park Chan-wook global recognition. The second film in The Vengeance Trilogy (and arguably the most well-known), Oldboy, was released one year later, in 2003. The film follows Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), who, after being mysteriously imprisoned in a small room for 15 years, is suspiciously released. His captor, the stoic and enigmatic Woo-jin (Yoo Ji-Tae) reveals himself as the one responsible for Oh Dae-su’s confinement, but challenges the unstable man to answer one simple question: why? As Oh Dae-su falls in love with a young sushi chef named Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong), his quest for vengeance and reason is undermined by the seeming banality of his suspected wrongdoing.

Throughout the film, Woo-jin reminds Oh Dae-su that “be it a rock or a grain of sand, in water they sink as the same,” and this sentiment is proven true when Oh Dae-su discovers the reason he was punished: for inadvertently spreading one rumor about Woo-jin in high school that led to the death of his sister. In one of the most shocking and polarizing twists in cinema history, Woo-jin reveals that his own plans of revenge are not over, and that he tricked Oh Dae-su and Mi-do into falling in love (and subsequently having sex). With this stunning and unforgivable revelation, Woo-jin kills himself, leaving Oh Dae-su alone with his forever fractured life.

Strangely enough, those that criticized Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance as being too concerned with violence and gruesome brutality praised the even more macabre Oldboy for its full commitment to the depiction of man’s immorality and wickedness. However, much like Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, Oldboy presents profound ideas of duality when discussing unrestrained retribution. In the film, we see two individuals that live purely for retaliation. Oh Dae-su spends fifteen years fantasizing about killing whoever locked him in that room, and, in an almost superhuman sense, is invigorated by the very notion of reprisal, as we see him fight his way through hordes of men through a crowded hallway. Woo-jin, on the other hand, concocts a master fifteen year long plan with the sole purpose of punishing the man that he feels is responsible for the death of his sister. It is in this sense that Oldboy presents many dual perspectives to the concept of revenge: the purpose for seeking revenge (whether it be because of a microcosmic action or an entire life stripped of virtue), the means of seeking revenge (precise and cerebral punishment or visceral immediate violence), and the very notion that revenge itself can be double sided, involving two very capable and determined parties crumbling inwards on one another.

However, Park Chan-wook takes the idea of dualism one step farther than he does in any of the other films in his Vengeance Trilogy. By the end of the film, Oh Dae-su enlists the help of a hypnotist to eradicate the part of him that knows Mi-do is his daughter, presumably so they can live together peacefully. While he’s in a trance, the hypnotist suggests there are now two Oh Dae-sus, one that doesn’t know his secret, and the other one, the one that has died, does. By this, it seems Park Chan-wook is personifying virtue and sin, implying perhaps that good and evil (or at the very least pain and acceptance) are two conflicting forces within us all, further stretching his critical focus of dualism into the realm of the human subconscious.

LADY VENGEANCE

(2005)

“Big Atonement for big sins. Small Atonement for small sins.”

Two years after Oldboy garnered filmmaker Park Chan-wook international acclaim, he released the third and final film in The Vengeance Trilogy: Lady Vengeance. Like its predecessors, the film follows a protagonist on a journey to revenge, yet Lady Vengeance takes a rather unexpected turn around two thirds of the way through. Throughout the film, we follow Lee Geum-ja (Lee Yeong-ae), who, after being imprisoned for 13 years for a crime she did not commit, begins her plan to track down and kill Mr. Baek (Choi Min-sik), the man that was responsible for the death of a six-year-old boy following an attempted kidnap and ransom. After racking up a multitude of favors from fellow inmates in prison, Lee Geum-ja is finally able to capture and restrain Mr. Baek.

However, when she discovers small trinkets attached to his keychain (which we come to understand as trophies for his murders), Lee Geum-ja realizes that Mr. Baek is not simply a failed child kidnapper, but in reality a vile and irredeemable child serial killer, who has claimed five victims in total. Leaving Mr. Baek bound to a chair without any possibility at escape, Lee Geum-ja is able to convince all the victims’ parents to meet, where they agree to torture, mutilate, and kill the child murderer together. The film ends with Mr. Baek dead and Lee Geum-ja imploring her young daughter to live a virtuous and unstained life, like tofu.

The final film in The Vengeance Trilogy presents a final and important example of the duality of revenge. In Lady Vengeance, Lee Geum-ja makes a choice that characters in the previous two films did not (or could not), she must let her rage and eagerness for justice subside for those that are more deserving. She realizes that there are those that were wronged by Mr. Baek even more so than herself, therefore in an act of charity, albeit brutal, Lee Geum-ja gives others the chance to exact their vengeance on Mr. Baek. In what is perhaps the best example of poetic justice seen in the entirety of The Vengeance Trilogy, we see all those that lost a child to Mr. Baek finally able to exact equal punishment onto the evil man. The only person that arguably loses out on this act of cathartic revenge is Lee Geum-ja herself, who instead settles on shooting his dead body with a gun.

In this grizzly conclusion, Park Chan-wook presents yet another bittersweet sense of duality regarding the intricate concept of revenge: the duality of those wronged. For a majority of Lady Vengeance we are led to believe the titular Lee Geum-ja is the sole possessor of the burning desire for vengeance against Mr. Baek. It isn’t until this third act discovery that we see there’s another side to revenge, a side I’d argue is absent from the other films in The Vengeance Trilogy. We’ve seen the depths people are willing to go to seek justice, to punish others for sins committed, to retaliate for years of undying pain, but with the grieving parents in Lady Vengeance we see the other, non-committal, reluctant, and perhaps even truer to life form of revenge, not one perpetuated by obsession, but rather incited through grief.

The parents watch video tapes of their children recorded by Mr. Baek. They watch them struggle, cry out, and eventually die at the hands of a monster. While it could be argued their fury unleashed on Mr. Baek was instigated by momentary rage, it’s clear that because the initial action was done to a loved one, and not themselves, the main agent at work guiding them to use hammers, knives, and axes is anguish, not rage. In showing the two separate catalysts for revenge: both Lee Geum-ja’s hateful wrath and the parent’s bitter pain, Park Chan-wook presents us two complex emotions that can lead us to the same vengeful acts of violence.

Park Chan-wook’s The Vengeance Trilogy teaches a lot regarding revenge. It informs us that every vengeful act has cause and effect, or perpetrator and victim as seen in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. That both the means of exacting revenge and reasons for seeking retribution can be two-sided and in direct opposition of one another in Oldboy. And finally, that those wronged can be driven to the very outer edges of morality and virtue due to two deeply conflicting sentiments: anger and despair, which we see in Lady Vengeance.

These three films should be viewed as critical thinking pieces targeting our simplistic and one note understanding of the act of revenge. For too long revenge has been depicted and portrayed as a simple tale of wrongdoing made right, of a single character, driven by bitterness, punishing those that wronged them. The Vengeance Trilogy provides a truer and darker examination into revenge, one that is messy, convoluted, marked by causality and devoid of any clear ethics. In Park Chan-wook’s grimy and blood-stained world, every story has two perspectives, every motive has two sides, and every action cannot go unpunished. This is the world of The Vengeance Trilogy, and this is very much the world we live in.

Park Chan Wook’s Vengeance Trilogy is now available to rent and own. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, Oldboy will be re-released restored and remastered in 4k, in select US theaters from August 16, 2023.