We interview director Sylvain Chomet about A Magnificent Life (Marcel et Monsieur Pagnol), making films in English, and the changes in the animation process.

One of the highlights of this year’s Cannes Film Festival was a project that brought together two legends of French filmmaking from two different timeframes, and from two very different ways of making films. A Magnificent Life (Marcel et Monsieur Pagnol) tells the story of one of France’s most beloved artists. Marcel Pagnol (1875 – 1974) has long been regarded as one of the finest writers and filmmakers France produced in the 20th century, with significant contributions to literature, theatre and film. His most famous novel is 1963’s “L’Eau des Collines”, adapted as Claude Berri’s masterworks Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources. As a director, Pagnol adapted several of his own works, including the plays “Manon”, “Fanny” and “Topaze”. His works as both filmmaker and writer continue to be admired to this day.

When it came to making a film about Pagnol’s life, his estate approached writer-director Sylvain Chomet about making a documentary. A legend in French animation, four-time Academy Award nominee Chomet has directed such beloved works as The Triplets of Belleville and The Illusionist. As he reveals in our interview, A Magnificent Life morphed into an animated biopic, one that he hopes will bring Pagnol’s work to audiences outside France. Among many thing we learned in our interview, the film will receive releases in French and English, with Welsh actors recreating the effect of the musicality of Pagnol’s native Marseille accent.

We met Chomet on a sunny afternoon at the Cannes Film Festival after its premiere screening, and discussed how this project and his filmmaking in general have evolved. Read the interview below!

Sylvain Chomet on Marcel Pagnol

When you were approached about making a film about Marcel Pagnol by his estate, did you think it was a fit for animation?

Sylvain Chomet: No, because it wasn’t supposed to be an animation at all! It was supposed to be a classical documentary with archive footage, etc. I remember that documentary The Kid Stays In The Picture [the 2002 adaptation of legendary Hollywood producer Robert Evans’ biography], and they fill in the missing parts of his life in animation. The Pagnols showed that to me, and I said it’s a nice documentary, and it works for a producer. I said, “If you want me to do a documentary, let’s do it the classical way.”

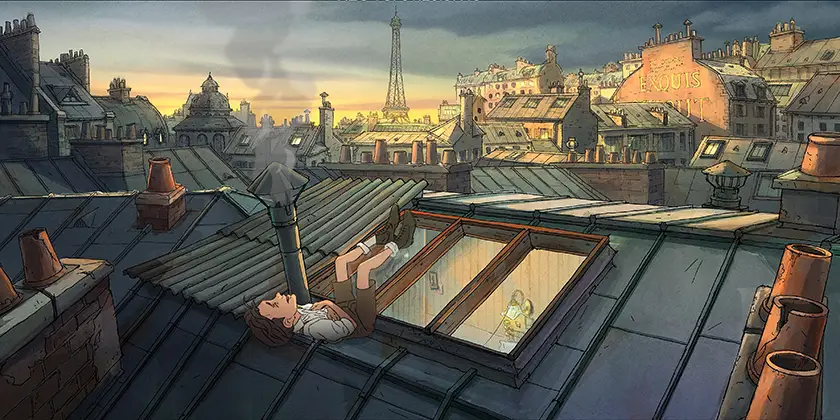

I wanted to make a documentary because I’d never done it, and I was sure I could do something nice with that. I thought animation would be too long, too expensive, too complicated to finance. But I animated just one scene – Raimu on the Pagnol having an argument – and it was shown to the financiers. Suddenly everyone says, “We don’t care about the documentary. There are already documentaries on Pagnol. We want the animation!” I said we should be broad, and just do a biopic in animation, which has never been done, basically. That’s going to be quite interesting. We decided the real life events would be in animation, and scenes from the real films would be shown in live action.

You were already a fan of Pagnol’s work. Which were you a bigger fan of: his writing or his films?

S.C.: I started with his books, but everything he did was just very enjoyable for me. When he recalled and wrote about his childhood memories [in his autobiographical ‘Souvenirs d’enfance’ series (1957-77)], this was the first experience for me of having fun reading. Some of the work I was really bored with, but this series came along, and it spoke to me because I was the same age as he was in the books. The films came later, but when I saw them, I fell in love. They were black and white movies from the 1930s, so I started to become a cinephile because of his films. The only thing I really wasn’t into was his theater pieces. It’s complicated in a way, because most of his theater successes were actually translated into films.

Sylvain Chomet on the evolution of animated filmmaking

The film marks some firsts for you. How did you find the transition from animation on film to digital filmmaking?

Sylvain Chomet: I started animation at the end of the 1980s, and at that time when I began in London, everything was hand drawn. Everything was painted on celluloid, and we were working with rostrum cameras. There was absolutely nothing digital, apart from what was the early beginning of the line test [the process by which an animator checks the flow of a drawing from frame to frame] in digital. I remember that was a big improvement, because you can do a lot of line tests very quickly. I started to do my first films with the line test on black and white drawings. The Old Lady and the Pigeons (1997) was completely classical: rostrum camera, celluloid, all that. But I always had an eye on technology. For The Triplets of Belleville, it was still animation on paper, but the cameras were becoming digital. For the background color, for example, everything was hand-drawn, but we were using Photoshop. Then, The Illusionist has even more digital work in it.

This film is the first time for me where there’s no paper; it’s basically gone, which I’m very happy with. But it’s still the same; you’re using your hands and your brain, but you have some very, very neat tools to use, and that’s great. The computer is not doing anything to the quality of what you’re going to show. Really, it’s still handmade, but with a very clever tool, which I love. It’s really good because you can draw the animation, and then people are going to do the backgrounds, and then you can mix them straight away. Everything communicates, so you can do really very sophisticated movies in a short time.

Another first for you is animation with dialogue. Despite having Pagnol’s words to draw from, did you find the script daunting to write?

S.C.: It had to be done. The Illusionist was an adaptation of [Jacques] Tati, but I didn’t mind that you don’t have dialogue with Tati. He was a mime, and I’m not a very talkative writer. Pagnol was talkative, but because we know the way he writes, all the poésie his work has, it’s beautiful. His stories are quite dark; they’re not happy stories most of the time. They feature very serious subjects, but the way the people are expressing themselves is beautiful, and it’s very touching, and it overcomes the sadness of the subject. It’s actually quite an elegant way to go into darker material.

Sylvain Chomet on casting A Magnificent Life

Both French and English of the film versions feature impressive actors (Laurent Lafitte, Celyn Jones). Did you have any particular approach to casting?

Sylvain Chomet: The big names weren’t that important, but Laurent Lafitte was a plus because he’s really talented. I think the challenge for him was to convey Pagnol’s age over the years, and his changing accent. He loses his Marseille accent in Paris, and then it starts to come back, and he’s got a mixed accent at the end. It was very complicated, but Laurent is amazing, because you don’t recognize his voice. The character’s voice is distinct over the years, which is really great. People told me, “You have a different actor at the beginning, when he’s younger,” and I said, “No, it’s the same. It’s all Laurent.” I mean, the guy is really good. For the characters from Marseille, we decided to go with the real Marseille accent, so it was important that the voice was faithful to the character and not to the actor. Laurent is a big name in France, but, you know, he blends into his character.

How did you find the process of translating the film from French to English?

S.C.: It was interesting, because I really wanted the English version to work as well as the French version. This was complicated because we had to translate the accent. Pagnol’s south of France accent is very different from the Parisian accent. Someone said, “Well, just do the Marseille accent, but speak English.” We did that, and it sounded Italian! It sounded like The Godfather, really weird. We decided that the basic French would be Oxford English. The rough Parisians would be Cockney. Then we wondered where we would find an accent for Marseille? The Marseille accent is very lively and very musical. I suggested Irish; yes, it’s musical, but a lot of people know the Irish accent already. Same problem with Scottish. Then we decided on Welsh, because it’s not as well-known. It works with the characters and their hand gestures. There are a lot of different Welsh accents, which was great as well, because some of the actors have very different accents, some not as musical as others.

The English version came out really well, but it was a very different way of working. I really enjoyed the post-synchronization [Matching voices to pre-existing animation] in English. It’s very precise, and I found the actors amazing. They do synchronization very well, all of them. It has to be spot-on, and I was really surprised by the quality. It was the first time for me to actually do post-synchronization on one of my films, and I’m very happy with both versions, but I really enjoyed doing the English one. It was challenging as well, you know, because some stuff will be different the way I wrote it in French. For example, Marcel was an English teacher, which in England doesn’t work, so we decided that he was going to be a Latin teacher. I called Nicolas Pagnol (Marcel’s grandson) and asked, “Are you okay with that?” He told me Marcel was also a Latin teacher!

Bringing Marcel Pagnol to a wider audience

This is a particularly French production. It’s set there. It’s all French characters. It’s Pagnon, after all. What do you hope non-French audiences take from the film?

Sylvain Chomet: Well, the idea was for Pagnol’s original language to be English. The thing was actually to make it accessible to English speakers. I directed the English version before the French version. For us, the aim was that you don’t have to know Pagnol just to go into it. It’s the story of a man, a story of cinema, of creation, of loss. It has a lot of subjects which are universal, so you don’t have to know Pagnol. It was like The Aviator, the Scorsese film with Leonardo DiCaprio. You don’t have to know who Howard Hughes is. Most people didn’t know who he was, but his life is amazing. Any story about cinema translates.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

A Magnificent Life (Marcel et Monsieur Pagnol) had its World Premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, as a Special Screening, on May 17, 2025. The film will be released in French cinemas on October 15, 2025.

Header credits: Director Sylvain Chomet poses for a portrait shoot during the 78th Cannes Film Festival on May 18, 2025 in Cannes, France (Vlad Vdk/Getty Images), Official Poster for A Magnificent Life (What the Prod, Bidibul Productions, Picture Box / Wild Bunch)