With an overall presentation that truly elevates it beyond a film and into an experience, Spirited Away earns its status as Hayao Miyazaki ’s magnum opus.

When reviewing a movie, there are a few phrases that I avoid at all costs. One of them is “XXX is not a film, it’s an experience.” I get it: it’s tempting to just put that up there because the film in question really felt more than just moving images on a screen, but at this point, the phrase has become a real life cliché with how many times it has been just thrown out by people until it has lost all meaning. Which leaves me at a bit of a bind today, because I have nothing left if I don’t call Spirited Away an experience.

Directed by Hayao Miyazaki, Spirited Away (also known as Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, which literally translates to Sen and Chihiro’s Spiriting Away) follows a ten-year old girl named Chihiro Ogino (Rumi Hiiragi/Daveigh Chase). While moving to a new neighborhood, her father forgets to turn on Google maps, eventually getting them lost in a seemingly abandoned town. However, they soon find out they have entered a dreamy world of monsters and spirits. Chihiro’s parents are turned into pigs after trying to dine-and-dash, leaving her alone and scared with only the aid of a mysterious boy named Haku (Miyu Irino/Jason Marsden) to try and undo all of this and return home.

The reason I always end up saying “it’s an experience” when someone asks me what I think of Spirited Away is that I honestly don’t know whether any other descriptions can do it justice. I could talk about visuals, music, characters, and all that, like how I always do, but in this case, it would almost be a disservice to how much this film gets me. But whatever does the phrase “it’s an experience” actually mean?

Technically speaking, all films are experiences. They are a collection of images and sounds that leap out from the screen, surround you, then pull you into their world, immersing you for about 2 to 3 hours, making you feel alongside the characters. Whether it be yelling a battle cry alongside the Avengers or stifling a scream as Alien’s xenomorph prepares to open up more holes in your body than you’re comfortable with, a movie pulls you into that experience. However, the depth of that immersion can differ drastically depending on how a film is paced, shot, crafted, and acted. After all, cool visuals may not matter much if the audience cannot get attached to the characters, and a good story may not come across as strongly if the presentation is shoddy.

When you specifically call a film an experience, it’s based on how well the film pulls off that overall absorption. And with Spirited Away, every technical element pulls that off masterfully. The film’s plot is actually pretty simple. Chihiro gets spirited away and struggles to find a way to get her parents and herself back to the real world. But it’s how it’s presented, such as in the aforementioned scene, that elevates it beyond its simplicity and truly pulls you into what Chihiro is going through.

This comes through largely thanks to its stellar art and animation. Animation is a difficult thing to convey in writing, but there is a fluidity to the movements that exaggerate elements according to the situation. For instance, when Chihiro makes a horrified face, her hair starts sticking outward like a hedgehog. These elements may seem insignificant on their own, but they subtly add up to enhance the film’s visual impact. In addition, the art design stands out due to its creativity. Spirits and monsters in the film have an alien charm, inspired from traditional Japanese Shinto culture. This gives the overall world a mythical feeling, giving a sense that Chihiro is completely cut off from the modern world.

Individual scenes are also elevated by how they are presented. As Chihiro finds that her parents have been turned into pigs and runs through the streets of this strange town, night begins to fall, and its residents start to emerge. The overall colors grow darker, and despite the previously abandoned-looking city growing livelier with movement, the actual residents are drawn as shadowy blobs, an excellent contrast that makes it clear Chihiro doesn’t belong here. When I first witnessed that scene, it genuinely scared me, because those visuals sold me on how horrifying this must be to a young girl, left in a nightmarish wonderland after she breaks down on the ground.

However, there is another element of the film’s shining presentation that is just as important, and that is pacing. What’s notable about the pacing is the amount of slow moments it has. At first thought, slow pacing wouldn’t sound like a good thing. If a film just loiters around, you’re likely to get bored. You’ll start noticing you have a particularly annoying popcorn kernel stuck between your teeth, and bathroom urges will build up. But I find slower moments are exactly what a movie needs to fully pull you in. When everything in a film happens to always drive the plot forward, it is efficient. Yet it also leaves less room to breathe, less room to reflect on what just happened. Therefore, the movie feels colder, more artificial.

With Spirited Away, there are moments where characters just sit down and reflect, sometimes without any dialogue, just taking in the moment along with the audience. For instance, the day after Chihiro’s parents turn into pigs, Chihiro sits down in a flower garden and eats breakfast with Haku by her side. Eventually, her emotions from the day before start welling up, and she cries. When you really break the scene down, it’s just a solid minute of eating and crying. It might even seem unnecessary. Yet during that scene, we start to think about just how the situation may seem to her, how hopeless she must feel. We’re taking that time to dwell not on plot, but solely on her emotions. It’s something that allows us to truly feel for her journey and be immersed in it.

This isn’t to say that there’s not much substance in the actual story. Spirited Away carries poignant messages about a variety of relevant topics, ranging from toxic work culture that eventually makes one lose themselves, to the growth from adolescence, the overpowering nature of greed, and environmental pollution. They add even more to unpack with the film, like finding out the last layer of a matryoshka actually has ten more dolls to go.

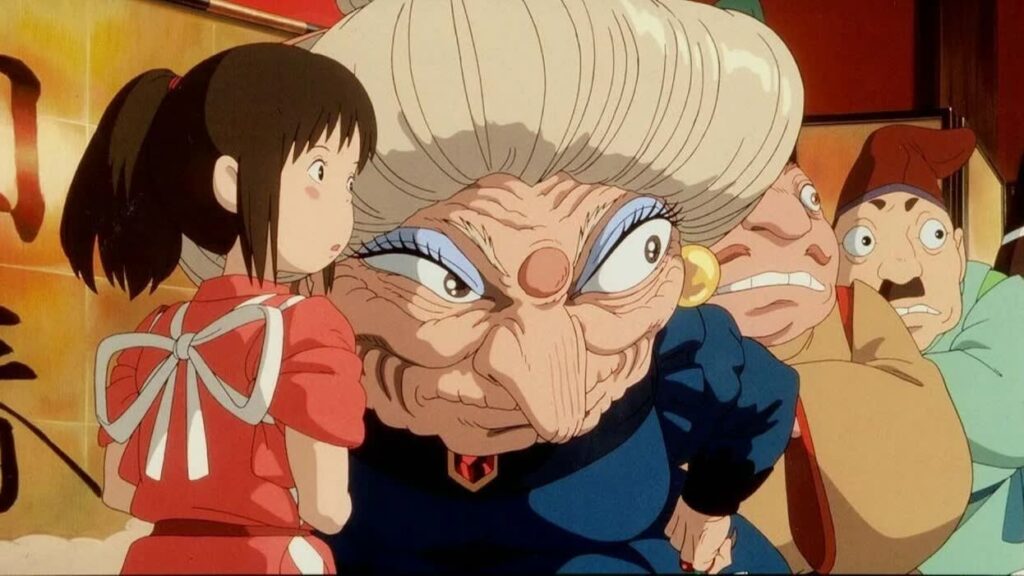

While some themes, such as material greed, may seem a bit clichéd, there is a certain nuance to them here that makes the movie still feel fresh. The main “villain” of the film, Yubaba (Mari Natsuki/Suzanne Pleshette), is a witch who holds multiple employees under contract in her bathhouse, including Chihiro. She is the embodiment of avarice, wanting more profits and seeing her staff as tools, and she also represents the harsh system of work in society that saps people of drive and youth.

Yet we also get to see parts of her character that aren’t all about the money. Despite her contracts being practically eternal, she is still a fair employer. When Chihiro comes looking for work, Yubaba grudgingly gives it to her, despite not having a high opinion of her. When Chihiro ends up turning a huge profit for the bathhouse, she congratulates her and praises her in front of the whole staff. She is also revealed to be a truly loving, if rather overindulgent, mother. Ultimately, she still isn’t a good person, but she isn’t completely one-dimensional, which allows her to feel more like a genuine character rather than a trope.

But out of all the themes there, the one I feel is the most powerful is the simultaneous presence and absence of personal growth. In a story, characters will often undergo growth throughout. Whether it be fixing a personal flaw, learning to accept another character, or growing a stronger will, they will learn and change through the trials they suffer through, and emerge a new person. Spirited Away appears to present the same sort of arc for Chihiro. She starts off whiny, timid, and scared of a flight of stairs (in her defense though, it was a very steep flight of stairs). However, she becomes more assertive throughout the film, taking actions on her own, showing considerably more maturity in the way she talks to other people.

Normally, you’d expect her journey to end like that. Yet, by the film’s end, you may notice Chihiro has actually regressed back to how she was in the beginning. When she first came into the magical world, she walked in clutching her mother for support. When she’s coming out, that exact image is repeated. She hasn’t really grown more assertive; she doesn’t pull her parents out of there in a heroic fashion. Despite everything she went through, she is still ultimately a little kid, and will probably remain that way for a while.

While this may seem odd for some, I find that refreshing and quite realistic. While growing up is a part of life, it doesn’t happen in an instant. You may learn a few lessons about the world or yourself, but you would still retain a sense of innocence for most of your childhood. It’s that sort of duality that makes up a believable person. Not to say that a character changing entirely through one event, aka the Ebenezer Scrooge syndrome, can’t work, but in this case, I welcome the nuance.

And it’s not like Chihiro has completely lost everything she has experienced. While she ultimately loses her memories of everything that happened in that world, she still has the hairband she received as a gift from there, and when she looks back for a moment, there is a sense of calmness about her. The growth from her ordeals is still there, but she just doesn’t know it yet. We all have that sort of maturity inside of us, we just need time to fully realize it.

The biggest thing I respect about the film is how natural these sorts of themes feel within the story. Sometimes, a film can become overzealous with how much it wants to talk about that the actual story becomes an afterthought. Deep themes should be like the cooking techniques behind a restaurant dish: a bonus that enhances the film rather than overtaking it. If a film is great on its basic merits, it will organically invite curiosity and discussion on what it was trying to say.

In the case of Spirited Away, the themes are there, but they are not flaunted right in our faces, and when some themes come forward, they are shown through the natural actions of the characters. For instance, when Chihiro’s parents become pigs, it’s because they eat at a seemingly abandoned restaurant without permission, thinking they can just pay the owner when they get back. That is a sign of consumerism running through modern society and how it can turn us into metaphorical pigs of the economy. But it still works just as powerfully when you see it as what it is: Chihiro’s parents falling prey to this strange magical world, leaving Chihiro scared and alone.

Therefore, what we get in the end is a movie that hits deep through its beautifully presented story alone. I am satisfied with a general viewing, and it leaves me with food for thought as an extra incentive to come back and examine it further. Spirited Away is the tale of a young girl lost and found in a fantastical world, and also a slice of childhood expanded into an adventure, presented in a way that doesn’t feel manufactured.

That is why I can comfortably call this film an experience. Spirited Away has consistently been considered Miyazaki’s magnum opus, and it’s not hard to see why. There is creativity and depth in every element of the film, all of which help immerse me no matter how many times I come back to it. While I don’t think there is any objectively perfect film out there, this has always been – and always will be – my perfect film.

Spirited Away is now available to watch on digital, on demand, and on DVD and Blu-Ray.