Speaking Parts presents a strangely absorbing story of connection and desire, interrogating our relationship with the screen image and video technology.

“There is nothing special about words,” a dejected Lisa (Arsinée Khanjian) says as she explains her strange viewing habits to a video store clerk named Eddy (Tony Nardi). Obsessively in love with her coworker Lance (Michael McManus), Lisa rents the films that he stars in as an extra to watch his scenes, the most intimate way she can connect with him. Lance is a cold and distant actor whose custodian gig at a hotel is only a cover for his work as a gigolo serving wealthy guests. His latest client is Clara (Gabrielle Rose), a screenwriter who has just finished a script for a television movie. After Lance finds her script, he gives Clara his acting portfolio, and, after a successful audition for the lead role, he is given his first speaking part in a film. As they begin an affair, Clara seeks to use Lance to subvert the control of a powerful producer (David Hemblen) to change the script back to her original vision. Meanwhile, Lisa becomes entranced by the act of filming and is soon drawn into this web of power and seduction in a bid to rescue Lance.

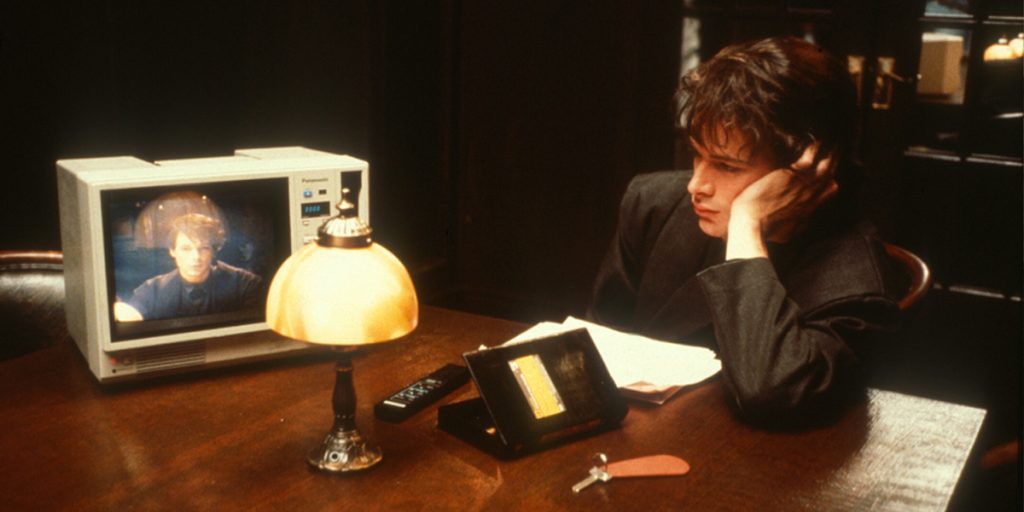

For a film more than 30 years old, Atom Egoyan’s Speaking Parts feels remarkably relevant in today’s world of Zoom calls, remote work, and digital social lives. Despite the outdated television screens and cameras, the film features several instances of video communication and interactions that highlight a reliance on technology to mediate human connection in a way that feels both futuristic and contemporary. In an early scene, Clara visits a “digital mausoleum” to watch a video to pay respects to a deceased relative. A conference room at the hotel serves as a key setting in the film where the television movie crew meets with the producer over a video call and Clara also records Lance’s audition in there on camera, which he later watches. Passion and desire are mediated through the screen, such as when Lance and Clara mutually masturbate over a video conference call, and Lisa’s desire for Lance manifests in an almost voyeuristic act of watching him onscreen in his films.

Lisa’s curiosity of the screen image inspires an interest in filmmaking after Eddy shows her an interview tape. When she helps him film a wedding, she interviews the bride and asks her if she has ever experienced doubts of her husband’s love. When Lisa upsets the couple, she realizes “I lost my objectivity,” reckoning with the responsibility and power wielded with the camera. Speaking Parts also explores a greater theme of media power, confronting notions of creative authority. It is the television producer, not Clara, the creator of her story based off a traumatic experience, that has control over the final draft of the script, which he commodifies into what he believes to be the best “product” for a wide audience. “This moves me so much I want to make it into a very fine film. Something I can share with millions of people,” he tells Lance, who challenges him over changes in the script. He reminds Lance that “people have always watched what I’d like to watch,” justifying his creative authority and boasting his influence over the industry. Media experiences, Speaking Parts seems to suggest, are packaged commodities, and even though we use them to facilitate familiar events or emotions, they cannot replicate genuine experiences.

A film of showing more than telling, Speaking Parts is often difficult to engage with, inaccessible both emotionally and narratively at times. Its fragmented narrative eschews much exposition, leaving the viewer with the task of piecing together a coherent picture of the story. Viewers might also find the film’s cold and remote tone off-putting, especially with the terse performances that highlight an awkward sense of detachment and inability to communicate. Yet, if you can overcome these hurdles, Speaking Parts is a strangely rewarding experience with its perceptive perspective on media interactions and power, and its beguiling mysteries slyly invite further rewatches.