Space: The Longest Goodbye, a documentary about the psychological toll of space travel, raises many questions while providing few answers.

Director: Ido Mizrahy

Genre: Documentary

Run Time: 87′

US Release: March 8, 2024 (limited theatrical) / May 6, 2024 (PBS)

UK Release: TBA

Where to watch: PBS

In The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s journalistic exploration of the beginning of the United States space program, Wolfe contends that in order to become an astronaut, one needs “the right stuff”- courage, ambition and mental fortitude. Space: The Longest Goodbye, the Sundance Film Festival premiering documentary from Ido Mizrahy, makes a compelling argument for mental fortitude being the most important quality in an astronaut.

In space no one can hear you speak, let alone scream. Traveling in space takes one away from friends and loved ones, and places you in a cramped, boxy container. There is little variety in the scenery during space travel, no natural way for your body and mind to differentiate between night and day, and the only people to talk to are the handful of others on the mission that you are stuck next to 24/7. According to NASA’s official website, space missions will require the team to live in a space the size of a studio apartment for up to two and a half years. Space travel, for all of its wonders, is claustrophobic and isolating. Through interviews and archive footage, The Longest Goodbye examines the mental toll behind the grandeur of space travel, taking you behind the curtain into NASA’s attempts to mentally prepare astronauts for the ordeal.

For Ido Mizrahy, the way into the story that he wants to tell in The Longest Goodbye is through astronaut Kayla Barron. She was a part of SpaceX’s journey to the International Space Station, and is a potential candidate for a three year mission to Mars. In interviews, Barron and her husband, Tom Barron, discuss the effect of long periods of time away from one another on their relationship and future. The doc jumps back to 2007 and we see astronaut Cady Coleman’s attempts to stay connected to her family during a six month mission to the International Space Station through video chat. This includes a compelling moment when Coleman is asked to parent from outer space and confront her young son about a fight he had with his grandmother. While this section adequately articulates the loneliness and isolation of space, unfortunately it only scratches the surface of the effect of a long-term separation on a family and its long term consequences.

Dr. Jack Stuster, an anthropologist consulting for NASA, explains that the governmental agency has an environment for engineers, and “soft, squishy humans are completely unfathomable to engineers.” How can such a group be supportive needs of people such as Kayla Barron and Cady Coleman and their family? Talking head interviews with behavioral scientists and psychologists, including Dr. Al Holland, NASA’s senior operational psychologist, describe the history of psychology within NASA and efforts to study the psychological effect of space travel. Featured heavily throughout the documentary in a poorly lit talking head, Holland was a Houston-based psychologist brought in by NASA in the 1980s to evaluate astronauts during the selection process, and would go on to assemble a psychological preparedness team.

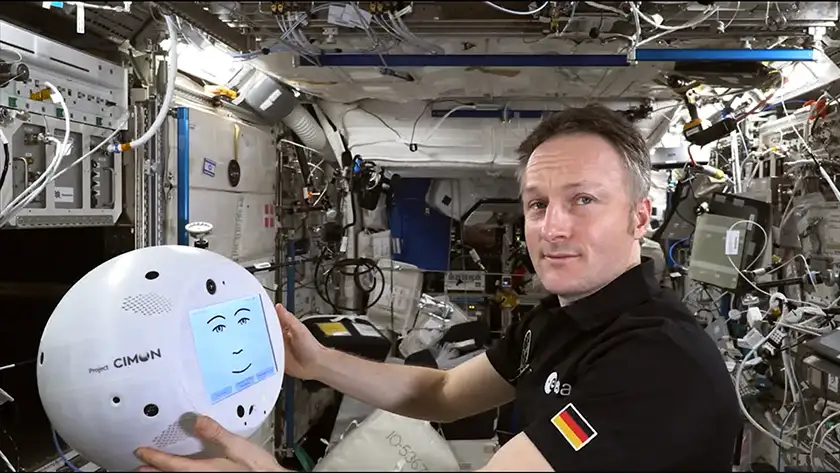

Other scientists interviewed for the documentary describe experiments with AI: virtual reality and hibernation in order to ease the ordeal of space travel. A robot called CIMON is introduced who could potentially provide the astronauts with companionship. The Longest Goodbye does not contend with the psychological effects on a human of dealing with only the rote, pre-programmed phrases of a robot, and the fall into the uncanny valley that could occur. No one discussing CIMON seems aware of a movie called 2001: A Space Odyssey and a computer program named HAL-9000. Books are visible in footage on the space ships, and Coleman is shown playing a flute, but there is no discussion of the role that art could play in the astronauts’ lives.

From the introduction of the Mercury Seven to the public scene in 1959, astronauts have captured the imagination, becoming a sort of superhero capable of reaching the height of human accomplishment and bravery, boldly going where no man had gone before. Think about how many children say they want to be astronauts when they grow up. Most discussion of space travel centers around the romance and adventure. It is commendable and invigorating to watch The Longest Goodbye interrogate space travel from a different angle, and a barely trodden one at that. Many viewers of The Longest Goodbye may find that they never even considered the problems with space travel raised by the documentary’s interview subjects.

Yet, where the documentary struggles is in fact that it raises more questions than answers, pokes at more threads than it is willing to unravel. The documentary’s eyes were bigger than its stomach, as it were. The subject is simply too great for a documentary to do justice within 87 minutes. Ultimately, The Longest Goodbye ends up feeling like a day trip to Disneyland. You had a wonderful time, and were able to ride Space Mountain, but missed out on an entire world of rides and experiences, only spotting Cinderella’s Castle and the Haunted Mansion from a distance. The Longest Goodbye is greater than the sum of its parts, benefitting from a strong central concept that is able to provoke thoughts and questions in the audience’s minds that are left unexplored within the body of the documentary.

Space: The Longest Goodbye is now available to stream.