We interview director and producer Robert Gordon about Newport Folk Festival documentary Newport & the Great Folk Dream, premiering this week at the Venice Film Festival.

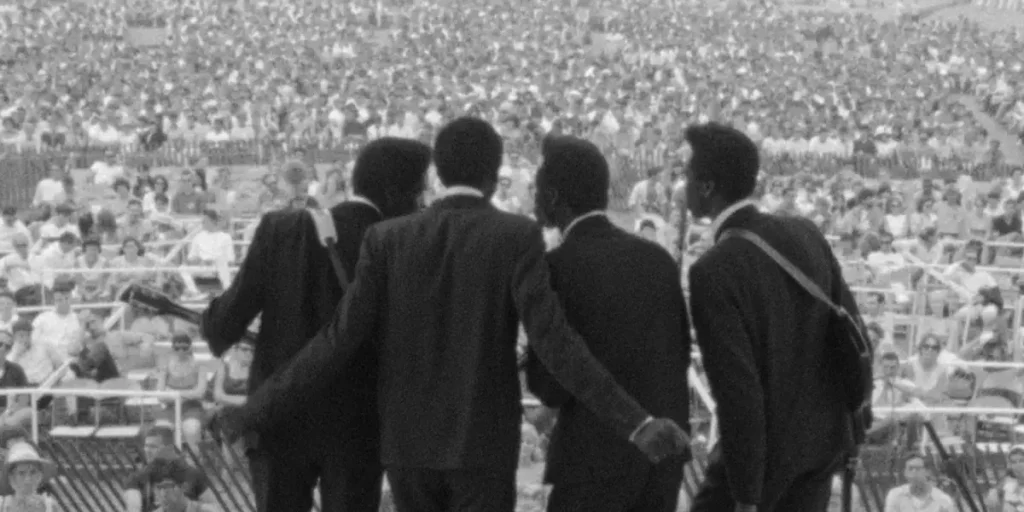

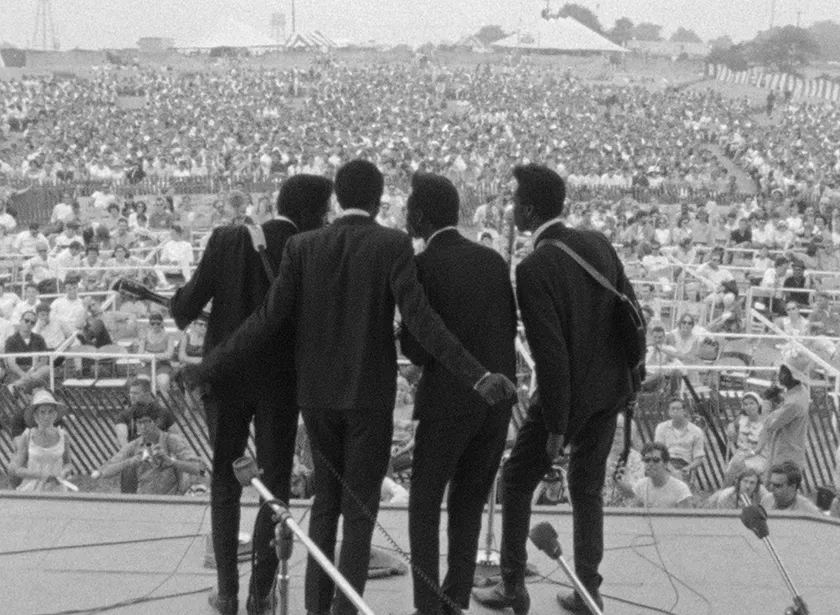

“Oh to be young at Newport in the summer of 65,” says the narrator at the start of filmmakers Robert Gordon and Joe Lauro’s Newport & the Great Folk Dream, which makes us experience just that. Drawn from previously unseen archival footage from the late documentarian Murray Lerner, who had intended to make an expanded version of his 1967 movie Festival before his death in 2017, the documentary was originally born as a project about the element of protest in folk music. Eventually, it evolved into something else: a film about the Newport Folk Festival in the 1960s that’s absolutely jam-packed with content, acting both as an historical and socio-political document and as a potent meditation on change, art, democracy, and the power of community.

With a total of 68 musical numbers, 30+ interviews, and historical footage of what was happening in the country at the time, Newport & the Great Folk Dream is an energetic, captivating documentary that will have you dancing on your seat with footage of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and so many more artists. But it will also make you think, surprising you with the depth of its themes and show you that folk music isn’t what you thought it was.

Newport & the Great Folk Dream will have its World Premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 5, 2025. Ahead of the screening, we sat down for an interview with director and producer Robert Gordon. Here’s what he told us about “listening to the footage” with producer Joe Lauro, and editor-producer Laura Jean Hocking to make the film take shape, the impact of A Complete Unknown on the film, Bob Dylan and the evolution of folk music, footage that surprised him, how the documentary is about diversity and democracy, and more.

Robert Gordon on “Listening to the Footage” to Assemble Newport & the Great Folk Dream

Congratulations for this incredible film! I counted more than 50 musical performances, on top of so many interviews and some great historical footage. Every single scene is so packed with content that you can’t take your eyes off it for a moment, and yet… it’s so short! [Robert laughs] Please tell me more about how you put it all together!

Robert Gordon: Well, we did have 80 hours of footage and interviews. The first thing we did was just watch everything. The editor [Laura Jean Hocking] and I sat down and watched it all, in whatever order. Everything had been synced up already by Murray Lerner’s team before my partner Joe [Lauro, founder and CEO of Historic Films Archive, and the film’s producer] bought the archive. We sat down and started watching everything, just to see who was playing, so we could pick what artists were going to be in the film, and of those artists, which songs. We just tried to make an A-list. It was a lot of material, and there were a lot of surprises.

We started putting together a film and had a rough-cut screening that was followed by a discussion. After that discussion, we actually took a left turn and started making a movie that was about the intersection of this festival and the Civil Rights Movement – in particular, this group called SNCC: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. We had footage of SNCC having a booth the Newport Folk Festival for four years.

The Freedom Singers are part of SNCC. We started doing these interviews, and we got really far along on a movie that was about this intersection… Until we had another test screening, and audiences told us: You know, every time you leave your footage, we really get mad at you, because your footage is new and we’ve never seen it before, and it’s beautiful, and it’s exciting. The Civil Rights footage is somewhat familiar, even though you have a lot of new information.

We were 80-90% finished, and we stopped. We assessed where we were and we started over. [smiles to himself] Because I love a project like this, which is like a puzzle. All the elements are there: You turn over the box and there are all these pieces on the table, and now you have to make a movie out of these pieces. I love that challenge. I did it once before with footage shot by the photographer William Eggleston [Stranded in Canton, 2005]. And the thing is, we were not listening to the footage. We were telling the footage that we wanted to make this movie about it and the civil rights movement.

So we started over, and listened to the footage. It was very humbling and mildly traumatic, but we knew it was the right thing to do. And then, once we got going, the footage led the way, and we just ran to keep up with what it was telling us. And we got this film that we really loved, which showcased all this wide variety of performers and told a story about adapting to change, and also about diversity and democracy.

Getting Newport & the Great Folk Dream Together and the Impact of A Complete Unknown on the Movie

Was it difficult to get the film made?

Robert Gordon: Joe and I began working on this before COVID. We cut a trailer and we took the project out to a few places to see if they would be interested in backing it. But everybody said, “Folk music, who cares?” But I’ve experienced this before. I made a film called Best of Enemies [a 2015 documentary about the 1968 televised debates between Gore Vidal and William F. Buckley.], which was about civil discourse [and asked the question]: when did civil discourse become uncivil?

My partner and I – a different partner – we would leave these meetings where people would go, “Yeah, yeah… So what?” We were like, “What are we saying wrong?” Because we knew that this was so timely and so relevant to now, and so important. Why weren’t the people we were telling this to receiving what we were telling them? Once we got the movie made, everybody embraced it: “Oh, my God, this is so pertinent to the moment.” So when we got a similar reaction here [the initial rejection from potential backers], it was not as daunting as the first time.

How long did it take you and Joe to put the whole film together?

Robert Gordon: From the time we started to watch until we finished the film, it took about two and a half years.

I read that you knew that James Mangold’s Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown, was coming out and you waited to release the film till after?

R.G.: Well, we finished our edit in September, and that movie was coming out in December. And we figured that nobody would be interested in making a move until they knew if that film was going to be successful or not. Then, when the reviews started coming out in early/mid-December, everything was positive, and once we got to see it, it was like, Oh, my God. My kids, who were in their twenties, were exposed to a lot of music. But then, my friends’ children became exposed to the Newport Folk Festival through the Bob Dylan film. So I felt like that film opened our audience a million fold.

Did knowing that A Complete Unknown would be released before Newport & the Great Folk Dream affect how you edited the film at all?

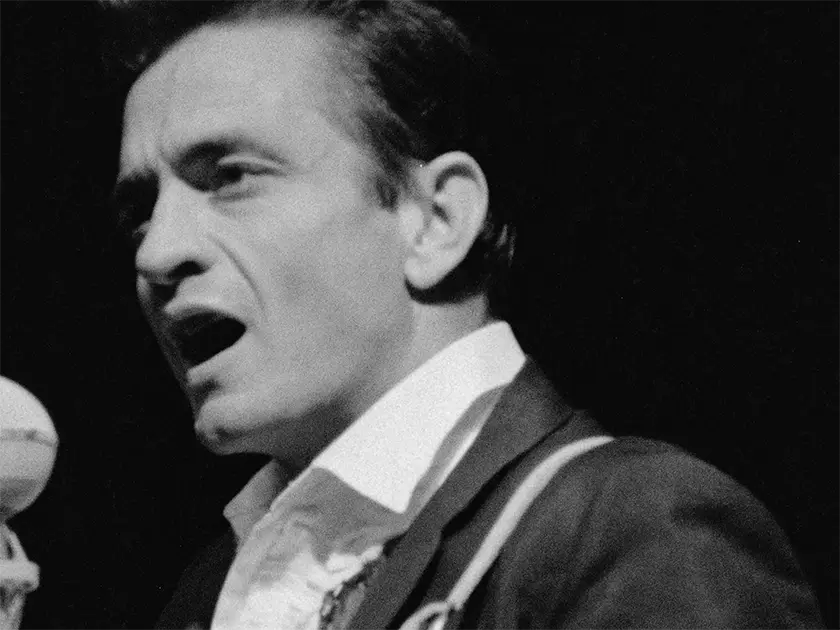

R.G.: No; we put our film together and we finished it. But after I saw A Complete Unknown, I did go back and change the opening. The original opening had been John Lee Hooker [there’s a beautiful scene in the film of Hooker playing “Boom Boom”], because we loved the groove, and John Lee Hooker is so startlingly handsome. And you don’t expect something like that at a folk festival.

But then, when I saw A Complete Unknown, I realized that the Johnny Cash connection would reach that audience better. Opening with Johnny Cash served a lot of the same purposes as opening with John Lee Hooker. With Johnny Cash, it’s kind of surprising to see him at this folk festival. His performance [of “Big River”] is so energetic. We don’t make a big deal out of this, but one of his band members is playing an electric guitar. There’s an electric guitar in the first song, and there’s an electric guitar in the Chambers Brothers too, before Bob Dylan plays in 1965.

“This Great Spirit is Really Over”: The Moment Bob Dylan Went Electric and the Evolution of Folk Music

One thing that really hit me is how you captured the evolution of music in that specific moment in time. At some point it starts to become clear that artists were moving toward the electric guitar, and Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band’s Maria Muldaur says, “the people who were making the music had no problem evolving.”

But then, there’s another scene – where Mel Lyman plays the harmonica after a very important moment – where you really captured how audiences reacted to this evolution. As Newport production manager Joe Boyd says in the film, “This was a moment you felt, ‘Oh my goodness. This great spirit is really over’ ”.

On one hand you have the artists, ready to evolve; on the other hand, the music belongs to the people too, and audiences don’t really know what to feel.

Robert Gordon: That moment where Bob Dylan goes electric and everybody is stunned, you hear the response. It’s a mix of cheering and booing; Something radical has happened, something has changed, and in the moment, people don’t know how to respond. That Bell Lyman harmonica is, I think, an elegy to the time. It says, “I know that somber harmonica, and it’s an old hymn.” Even though there are no words, the sound of that harmonica is saying, “We all knew something great, and that something great is changing.”

It’s like someone has died, you know? Their impact is still going to be with us, but we have to go on without them. Here, folk music hasn’t died, but it’s changed. Bob Dylan was the “main guy” at that point, in the folk world, and since Dylan has taken this big turn, [the people] are realizing that even traditions can change. Traditions are handed down generation to generation, but they change, they morph, they evolve.

Newport & the Great Folk Dream also shows that it wasn’t just Dylan wanting to go electric, like you said before. It was other artists too. I remember a scene where Mike Bloomfield from the Paul Butterfield Band gets really frustrated, saying something like “it’s stupid that at a folk festival, you can’t be rock n’ roll for some unnamed reason”.

R.G.: Exactly. It was Mike Bloomfield, called the Paul Butterfield Band. It’s like that Maria Muldauer comment you selected. He’s representing the musicians who are artists, and they’re not looking to create a product and then recreate it like a candy bar, the exact same, a million times. They want to change the recipe, and the shape, and the package, and continue to evolve. Mike Bloomfield is simply saying, Art has changed. Traditions change. Everything changes.

And with Dylan, it took some distance, but eventually people realized it was just a change; it was an evolution. It wasn’t the end. And certainly folk music is very alive today, although it’s become more personal and less communal. And one of our hopes is to reinvigorate the protest song, because there’s certainly a lot to protest.

Diversity and Democracy: Newport & the Great Folk Dream is a Message in a Bottle About the People in America

I’m so glad the film was made, because it is timely and relevant to this moment, like you said. What do you hope people will get from the film, especially international audiences in Venice?

R.G.: Well, a few things. There’s a very popular traditional folk song called “Michael, Row The Boat Ashore”. I think Peter, Paul and Mary did it in the 1960s. It’s this “Kumbaya, arms around each other, people swaying back and forth” song. The chorus is “Hallelujah, Michael, Row The Boat Ashore, Hallelujah” [the stereotypical image one would have in their minds when thinking of folk music].

But we found this version of that song by these people from the South Carolina Islands [The Moving Star Hall Singers], and it sounded so very different; it was really much more of a work song than a communal prayer. It was a work song. I thought it was so important to put that song right near the front of the film – it’s in the first 10 minutes – so that people would realize, “Hey, folk music is not what I thought it was”.

Then the goal after that was just to expand the definition of folk. That was in part because that was our experience, watching the 80 hours. I come from Memphis, Tennessee. I’ve been exposed to Blues since I was a kid. Blues has led me to gospel, soul music, folk music, and a wide variety of things, but I still was not prepared for the depth of the diversity that this folk festival put on.

That became a driving desire to share the diversity of folk music. As we worked on that, we became aware that that diversity was there because folk music was about democracy: it was about giving a voice to the people. The diversity we presented was a way for us to make a simple political statement: democracy thrives on diversity.

But I’m looking at my government. My government is trying to diminish diversity and enhance homogeny. And that is not good; it’s just not reality-based. And if it’s not reality-based, It’s not going to survive. We really hope that comes through.

You’re talking about what we want from audiences in Venice and international audiences. In a way, we look at this as a message in the bottle from the heavens, from the stars, which says we want people to know not everyone in America is like our present government. There’s a famous old movie from the ’50s, The Day the Earth Stood Still [from director Robert Wise], where these aliens come down and they bring this instrument of peace, which the American military immediately shoots out of their hands. And the space aliens say, “Too bad. That was the instrument that would have brought world peace”.

I feel like we are… [thinks] the forebearers of that message. We we want to remind people that there is a peaceful democratic contingency in America that wants to be heard.

Robert Gordon on the Footage that Surprised Him

Are there any scenes that really surprised you, or hit you in an unexpected way, when you watched the footage of the first time?

Robert Gordon: Well, a couple of things come to mind. I wasn’t raised on fife and drum music [where the fife (a small, high-pitched wooden flute) and one or more drums are played together], but I got exposed to it very early, and I’ve been a big fan of it for a long time. I’ve visited fife and drum picnics; I’ve written about it; I’ve filmed it. One of our co-producers had never seen it before: when it came up on the screen – and she’s a very knowledgeable person – she said, “What is that?” It was very informative to me to know that someone so knowledgeable about so many kinds of music had never seen this. That made me think, “Oh, very important to put it in”.

Another scene was very surprising as we saw the raw material. We would sit and view for eight hours at a time and make notes: it was really fun, and really exhausting. At the end of one of the days, I said to Laura Jean, “Okay, what’s next? What will we be starting with tomorrow?” She pulls up the next reel and says, “Blues House”. I said, “Oh, my God, we have a reel of footage from the Blues House?” [laughs] Robert Gordon. I said, “How long is it?” It was like, I don’t know… 12 minutes. I said, “Look, I know we’re tired. Let’s just look at it.” I said, “Scrub through it now. Let’s just get a sense of what’s there, and then we’ll watch it for real tomorrow.”

So we watched it, and it was not what we expected, but there’s this character who’s in the movie, Mississippi John Hurt, who is this joyful, serene man, and he has such a beautiful countenance. You look at his face and it just emits peace. We’re looking at him in this scene and he is not peaceful. He is extremely upset about something. We’re trying to figure out what’s going on. Then we watch it again, and we’re listening to what’s going on.

That’s when we hear Alan Lomax being mean to these performers. It was like, Oh, my God. I didn’t want to present that. [Folk music historian Alan Lomax was a consultant for the Newport Folk Festival, who often helped choose performenrs. He famously clashed with Bob Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman when Dylan went electric]. Then I found some other examples of Alan Lomax being less than forthcoming. I wasn’t anxious to be the guy who is constantly out to get Alan Lomax: I am not out to get Alan Lomax. I respect Alan Lomax, and I admire the work he did. But at the same time, research has proven that he did not necessarily have everyone’s best interests all the time. He was kind of selfish, and he could be demeaning to other people.

And so in the end, because we had the footage, because it was there, because it was so important, because it was a scene off the stage and inside one of the houses and had all these people together… We thought about this a lot and determined, “Well, we have to include it, and we have to present it for what it is.” We didn’t distort anything; We just present what it is. That was really kind of shocking to us: it was a surprising scene. Another surprising scene was finding the footage of Howlin’ Wolf.

Oh, I remember that scene! What was surprising about it?

R.G.: If you look back at the movie Festival, which is what all this footage was shot for, they show a Howlin’ Wolf performance, but what you hear is a chess recording: It’s not the live. And if you look, it’s not in sync. You never see Howlin’ Wolf sing anything, because they couldn’t find the audio. We had already begun the movie when Joe sent me a photograph of the Howlin’ Wolf boxes and said, “Found it.” I was like, “Oh, my God!”

Now we had the audio, and we had more footage. If there was anyone I I could go back in time and see perform, I would choose Howlin’ Wolf in Chicago in the mid 1950s – especially Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. To get to see Howlin’ Wolf in the early 1960s rolling around in the grass, fully energetic and winning this audience over so well… That was a real exciting scene to discover.

Bessie Jones, the Women in Newport & the Great Folk Dream, and the Visual Personality of the Movie

My favorite performance in the film is Bessie Jones and The Georgia Sea Isle Singers singing “Traveling’ Shoes”. There are so much energy and empathy in the performance, and Bessie Jones is just incredible.

Robert Gordon: …And she comes back [at the end of the performance] and takes a bow!

That’s right!

R.G.: I really thought that was great footage of them. Bessy Jones became one of my secret heroes of the movie. I know people into the history of folk music always talk about Bessy Jones, but now we get to put her full screen. I mean, she’s just beating that tambourine, but it’s like a whole band was there!

There are quite a lot of strong, cool women in this movie.

R.G.: Oh, good! We were somewhat conscious of that. My editor [Laura Jean Hocking] is a woman, and we had a very small team. Really, there was five of us: three women and two men. We were conscious about trying to make sure that we didn’t fall into a trap of representing just white men. But it was never an issue, because there were so many different kinds of music in there.

I also feel that the film itself has so much personality, visually. You have this gorgeous black and white, but then you also put some splashes of color in, from various types of text to the introductions to historical and political context – for example, the Kennedy ad. It’s footage from the 1960s, but it also gives off this modern, cool vibe.

R.G.: I’m really pleased. I can’t wait to tell the graphic designer that you liked it! What we told him was to use all the tools he had in the 21st century but to try to keep the look like it was in the early 1960s. And so that’s what we did. We didn’t try and make it look too fancy.

You mentioned the political ad when we go to those black and white balloons going up in the air at the Kennedy Convention, and then he has this orb come circled into the center, and it’s that color graphic [the “A Time for Greatness” poster] coming out as a balloon.

Yes, that’s it! I loved that transition.

R.G.: Well, great. None of it is by accident. We worked really hard to make the film have this feel.

Robert Gordon on Bringing Newport & the Great Folk Dream to the Venice Film Festival and His Future Projects

What does it feel like to bring the film to Venice?

Robert Gordon: It feels like a very high honor. In olden days, Kings would seal a proclamation with a wax stamp, and it feels like we have this very important antique stamp of high art.

And it’s the oldest film festival in the world.

R.G.: And huge films have come out of there. Actually, Festival premiered there in 1968.

I didn’t know that!

R.G.: We didn’t know that either! [laughs] That’s a really cool cycle. It really does feel like we’ve been stamped with a very high honor.

Are you working on anything else at the moment, book or film-wise?

R.G.: I’m an executive producer on a documentary about the Lorraine Motel [in Memphis, Tennessee], which was a black-owned motel, and Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated there. But the film is really about black entrepreneurship; the hotel is the vehicle for the story. It’s really coming along great, and I’m very excited about it.

I’m also working on a written piece about a black transgender soul singer from the 1950s named Jackie Shane. It’s a piece I’ve been working on and off for five years, when I’ve had time. I think it’s finally getting short enough that it can have a life. When I first wrote it, it was half as long as a book and three times as long as a long magazine article.

Both projects sound exciting, and we look forward to them. Thank you so much for speaking with us!

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Newport & the Great Folk Dream will have its World Premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 5, 2025.