Two music obsessed teens come of age during the pandemic in Plastic, a wistful tale held back from full potential by disjointed storytelling.

Director: Daisuke Miyazaki

Genre: Coming of Age, Music, Drama

Run Time: 104′

Language: Japanese, with English Subtitles

US Theatrical Release: October 4, 2024 at Metrograph (NY) for a one-week theatrical run

US Digital Release: October 4-December 4, 2024 on Metrograph At Home

UK Release: TBA

There are multiple times throughout Plastic when Ibuke (An Ogawa) and Jun (Takuma Fujie), the starry-eyed teenage leads of the movie, will find themselves listening to the same song at the same time, except they are in different parts of Japan. An aspect of fandom that has been forgotten in the age of social media and fan conventions, yet still rings true, is that being a fan of an artist or a particular piece of work is extremely personal. Sharing with an acquaintance a work of art that connected to your heart, that articulated feelings you never found the words for, is an act of vulnerability. That is what makes it so powerful when you find a fellow fan, someone who was spoken to by the art in the same way as you. You are not alone in the world.

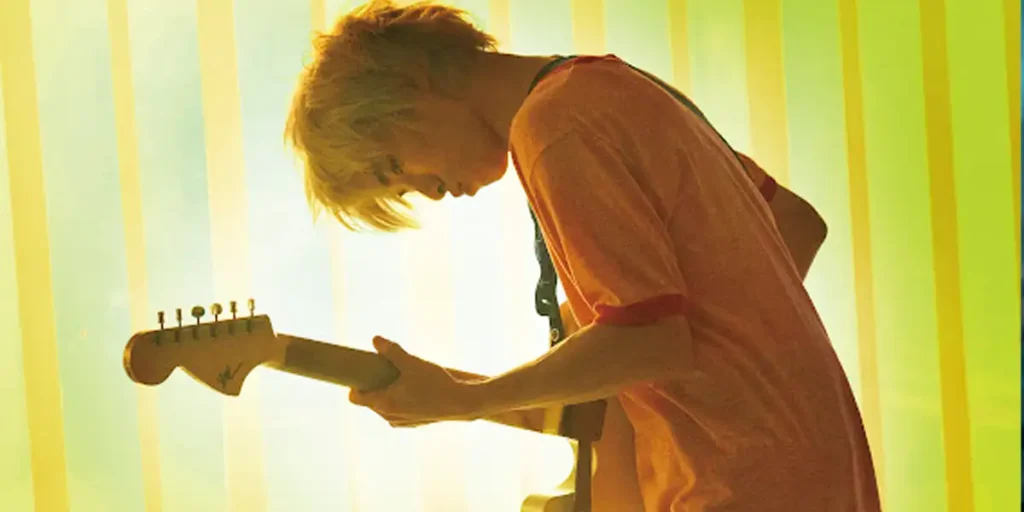

Ibuke and Jun find that connection with one another. Both would name Exne Kedy as their favorite band. Exne Kedy is a fictional band developed by musician Kensuke Ide for a 2020 concept album, “Contact from Exne Kedy And The Poltergeists”. In the world of Plastic, Exne Kedy were a glam/prog rock band of the 1970s, successful enough to play the Isle of Wight Festival in front of The Beatles and Bob Dylan, but only recording one album, “Strolling Planet ‘74”, before disbanding.

It’s Summer 2018. While bicycling home from school and listening to Exne Kedy, Iduke happens by Jun busking on the side of the street, playing the exact same song that she’s listening to. The two form a kinship over their mutual obsession with the glam rock group, and a tentative teenage romance begins. But really, the romance is with Exne Kedy. Iduke and Jun’s idea of a date is wandering the streets of Tokyo and tagging the highway underpass with Exne Kedy’s logo. When real life falls on the couple, in the form of Iduke’s college plans and Jun’s pie-in-the-sky dreams of rock superstardom, they buckle under the pressure and split.

At this point, the movie takes on a more vignette-heavy style, as the viewer pops in and out of Iduke and Jun’s life through the years as they deal with college, jobs, relationships and the COVID-19 pandemic. Years later, the two live in different parts of Japan, but there’s perhaps hope that they could run into each other when Exne Kedy announces a reunion concert.

In Peter Chan’s 1996 Comrades: Almost a Love Story, Maggie Cheung and Leon Lai’s fall in love to the sounds of Taiwanese pop star Teresa Teng, setting off a romance that will span decades and continents. Like with Comrades, in Plastic we jump to different periods in the characters’ life, peaking in on the ways that Iduke and Jun both change and stay the same as the years go by. Now Iduke has a boyfriend. Now Jun works at a bar during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Vignettes are not an untenable form of storytelling; many stories about the ugly realities of relationships have taken this approach, such as the aforementioned Comrades, or Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, or Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage. Unfortunately, Plastic lacks the rigor to make the scenes flow from one into another. It comes off as disjointed and jarring, taking the audience out of the present moment in order to figure out the new context for Iduke or Jun’s life. After the Summer 2018 section we never spend enough time with the character’s to get a clear picture, leaving gaps and smudges in the psychological picture. Some scenes just don’t connect. Metaphorically, it is as though for each vignette the viewer is taken into a pitch black room and must slowly adjust their eyesight to the darkness.

The writing for Plastic is well-observed, with a focus on small, character-based details that keeps the story away from treacly melodrama. This is a movie that loves its characters. It is in the romance that the script and filmmaking fail, and what a failure that is. Ogawa and Fuijie have a friendly, schoolyard chemistry that’s not ineffective during the early scenes of puppy love, but falls flat when the movie tries to convince the viewer that they may be cosmically fated soulmates. While I believed in Iduke and Jun’s romance with Exne Kedy, I never believed in the romance between just the two of them. In the words of the Internet meme, They seem to be very good friends.

Though other people flit in and out of Iduke and Jun’s lives, for all intents and purposes Plastic is a two-hander. Much is determined on the viewer’s desire to spend 104 minutes with these two personalities. Iduke is coltish and starry-eyed, flittering between the dreams of girlhood and the practical realities of adulthood. Ogawa is an enchanting screen presence, with a wide smile, crinkling eyes and a dewy, delicate charm. Fujie fares well in the light, comic scenes as Jun is discovering a fellow Exne Kedy devotee in Iduke, but stumbles during the heavier moments. He portrays Jun’s reserve with the body language of a somnambulist; wooden arms and a blank expression.

Throughout all of this, Kensuke Ide soars, bouncy and tuneful, in the background as the soundtrack to the characters’ lives. Plastic is a wistful, nostalgic coming-of-age story about the things we take with us into adulthood from our youth and the things we leave behind. While Plastic does not live up to all of its promise, it is able to capture how important music is during the teenage years. Those are years of emotional storms, uncertainty and dreams, the time when you are taking your first steps into the world independent of parents and guardians. Music can offer a haven from the tumultuousness of real life, and also articulate all the pain and confusion for you. The movie understands the way that music can connect itself to specific emotions and events, acting like a scrapbook for those memories.

Plastic will be released at Metrograph (NYC) on October 4, 2024, for an exclusive one-week NY theatrical run. On the same day, the film will also have its streaming premiere on Metrograph At Home, running for an exclusive limited engagement until December 4.