A slick sci-fi thriller with big ideas about AI justice, Mercy struggles with weak writing and a hollow mystery.

Director: Timur Bekmambetov

Genre: Sci-fi, Thriller, Mystery, Drama, Action, Crime, Whodunnit

Run Time: 100′

Rated: PG-13

Release Date: January 22, 2026

Where to Watch: In U.S. theaters, in U.K. and Irish cinemas, and globally in theatres

There’s a moment early in Mercy where the film feels like it’s about to ask a dangerous question. We’re introduced to a near-future Los Angeles where the justice system has been gutted and rebuilt around something called the Mercy Court, an experimental courtroom run entirely by an artificial intelligence judge named Maddox. No lawyers. No jury. No appeals. Just data, logic, and a strict ninety-minute countdown before a verdict is reached and punishment is carried out immediately.

It’s an unsettling setup, one that feels uncomfortably plausible especially today, with the evolution of AI. This premise alone is enough to spark anxiety before a single character speaks. For a brief stretch, Mercy seems poised to become a genuine interrogation of power and what happens when society mistakes efficiency for morality.

Then the film almost immediately backs away from that idea.

Instead of questioning the system it introduces, Mercy turns into a hollow murder mystery, playing dress up in futuristic screens and sleek production design, and more interested in moving fast than thinking deeply. The result is a film that looks busy and urgent at all times but feels strangely empty underneath, like a courtroom drama that never quite understands what it wants to put on trial.

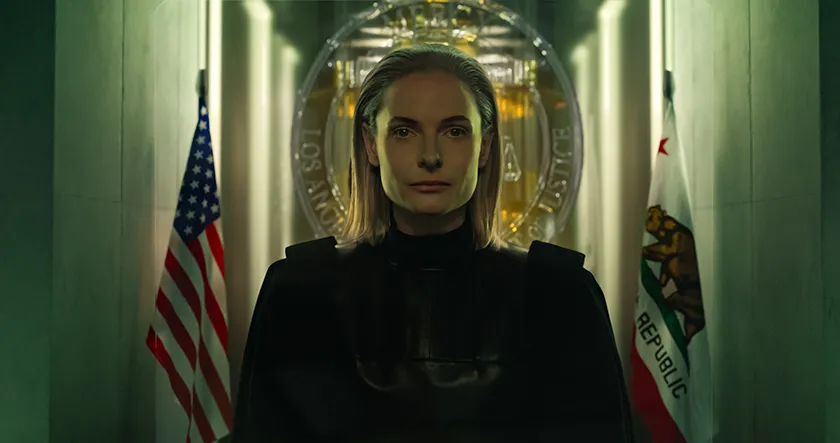

The story centers on Chris Raven (Chris Pratt, of Guardians of the Galaxy), an LAPD detective who wakes up strapped to a chair and finds himself accused of murdering his wife, Nicole (Annabelle Wallis, of Boss Level). There is a certain irony since Raven once championed the very AI system now judging him. His trial begins instantly, overseen by Judge Maddox, voiced and performed by Rebecca Ferguson with crisp authority and calm. If Raven cannot prove his innocence within ninety minutes, he will be executed on the spot.

From there, Mercy unfolds almost entirely within the courtroom, though visually it rarely feels confined. Director Timur Bekmambetov leans hard into a multi-screen presentation style. Security cameras multiply across the frame. Phone footage overlaps with police files. Social media posts pop up mid-conversation. Documents scroll by as live feeds update in real time. There’s always something moving or refreshing.

On a purely technical level, this approach often works. The constant visual motion creates a sense of urgency that mirrors the ticking clock. It keeps the film from feeling static and gives the investigation a frantic, real-time momentum. When Mercy is functioning as a visual experience, it can be genuinely engaging. The problem is that style becomes a substitute for substance.

The writing, by Marco van Belle, is shockingly thin for a film built around ideas this large. The Mercy Court system barely survives even basic scrutiny. Defendants receive no legal counsel, yet are granted unrestricted access to an entire city’s surveillance infrastructure. Law enforcement roles blur and shift depending on what the plot needs in that moment. Crime scene investigations appear rushed to the point of absurdity. The film wants the audience to accept these rules instantly without ever grounding them in believable logic.

World-building exists only at the most surface level. We’re told society has embraced this system, but never shown why. We’re told it’s efficient, but never shown its successes or failures beyond this single case. There’s no sense of public debate, no ethical friction, no human cost outside of the protagonist. The world feels less like a future shaped by policy and fear and more like a sketch written on the back of a napkin. That lack of foundation makes it nearly impossible to emotionally connect to anything happening onscreen. When the rules of the world don’t feel real, the stakes can’t feel real either.

Chris Pratt, to his credit, is genuinely trying. You can feel the effort in his performance, the strain of an actor attempting to inject desperation into material that rarely earns it. He sells the panic, the exhaustion, the fear of watching time run out. But he’s miscast for a role that would have required a quieter kind of intensity. Raven is written as a man haunted by addiction and guilt long before the trial begins, yet Pratt’s screen persona never quite disappears. The emotional beats land unevenly because the script never gives him solid ground to stand on.

Rebecca Ferguson fares better. Her vocal performance as Judge Maddox is the film’s strongest element. Controlled and eerily composed, she brings a chilling calmness to the role. Every line sounds calculated and faintly inhuman without drifting into caricature. If Mercy had leaned more heavily into her presence—into the discomfort of arguing with something incapable of empathy—it might have found its spine.

But the movie makes an odd choice. Rather than positioning the AI as something to fear or question, Mercy treats it almost like a reluctant ally. Maddox becomes less an embodiment of systemic danger and more a narrative obstacle or sidekick, occasionally nudging Raven toward clues. It’s a baffling tonal decision that renders the film strangely pro-AI at a time when skepticism should be baked into every frame.

The influence of Minority Report looms heavily throughout, from the visual language to the central idea of pre-emptive justice. The difference is that Spielberg’s film was deeply invested in the moral weight of its premise, while Mercy seems largely uninterested in it. It avoids engaging with the broader implications of AI in the legal system, despite being perfectly positioned to do so. Questions about bias, data manipulation, human error, and algorithmic prejudice are brushed aside in favor of plot mechanics.

And even as a mystery, the film struggles. The investigation is neither particularly clever nor emotionally resonant. Revelations arrive because the runtime demands them, not because the story builds naturally toward discovery. Twists feel undercooked. Motivations blur. When answers finally emerge, they lack impact because the groundwork was never laid.

What’s most frustrating about Mercy is that it keeps reminding you how much better it could have been. The premise is strong, the setting is ever so timely, the visual language is often compelling, and the pieces are there. They’re just never assembled into anything meaningful.

By the time the countdown reaches its end, the film hasn’t earned the tension it so desperately wanteds the audience to feel. Like with AI, everything here feels artificial but there’s no intelligence. Mercy wants to look forward, but it refuses to think forward. And in a story about the dangers of letting machines decide our fate, that lack of reflection may be its greatest failure.

Mercy (2026): Movie Plot & Recap

Synopsis:

Set in a near-future Los Angeles, Mercy follows detective Chris Raven, who is arrested for the murder of his wife and placed on trial in the experimental Mercy Court.

Pros:

- A visually dynamic presentation using multi-screen layouts, surveillance feeds, and digital overlays

- A strong vocal and physical performance from Rebecca Ferguson as the AI Judge Maddox

- The real-time countdown structure creates a constant sense of momentum

Cons:

- A severely underwritten script that avoids meaningful commentary on AI and justice

- The world-building collapses under basic scrutiny and lacks internal logic

- The mystery is poorly constructed and emotionally hollow

- An oddly pro-AI perspective undermines the film’s thematic potential

Mercy (2026) is now available to watch in U.S. theaters, in U.K. and Irish cinemas, and globally in theatres.