Stephen Soucy’s Merchant Ivory documentary gifts film lovers with an elegant and intimate look into one of the most important award winning partnerships in cinema.

“I am an Indian Muslim, Ruth is a German Jew, and Jim is a Protestant American. Someone once described us as a three-headed god. Maybe they should have called us a three-headed monster!” — Ismail Merchant.

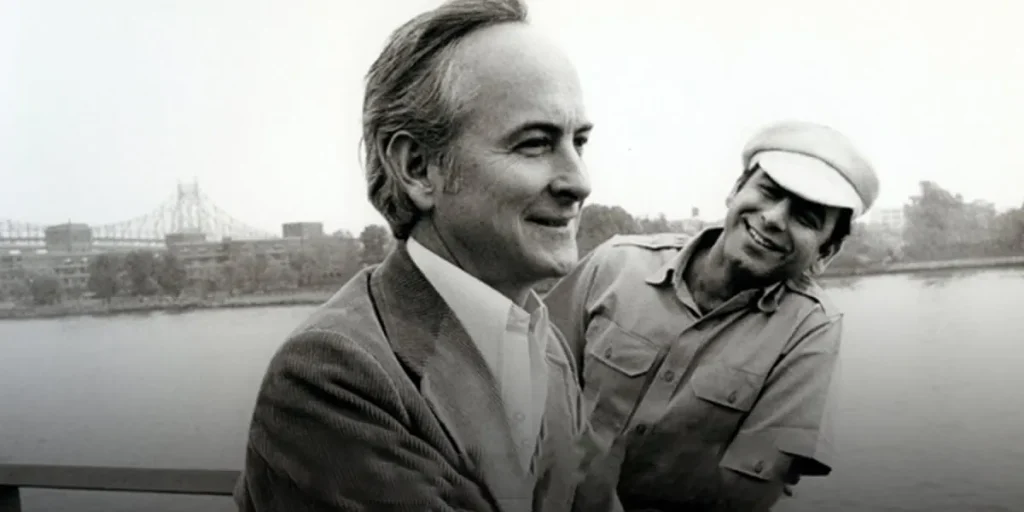

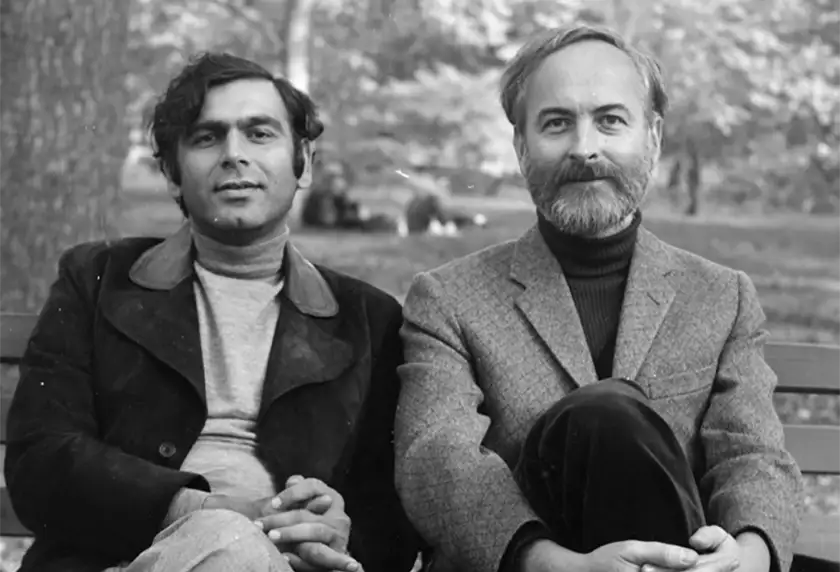

The feted production company Merchant Ivory is mostly known for period pieces and literary adaptations. However, the company which started when James Ivory and Ismail Merchant met as young men in America was far more than just frocks, class, and repression. Ironically, not a single member of the core quintet who made up the company was British at all. James Ivory was American, originally from Oregon. Ismail Merchant was from Mumbai in India. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala who wrote or adapted many of their major films was a German who had gone to live in India after her marriage. Composer Richard Robbins was from Massachusetts.

Of all four, only James Ivory survives, and is, at the time of writing, the oldest person to win an Academy Award for his adaptation of André Aciman’s novel “Call Me By Your Name” for director Luca Guadagnino. Under Merchant Ivory’s auspices, many actors and creators have won numerous awards: including Jenny Bevan for costume design, Jhabvala for adapted screenplay, and best actress for Emma Thompson. Yet, for all the E.M. Forster adaptations (A Room with a View, Howard’s End, and Maurice) or the Henry James (The Europeans, The Bostonians, The Golden Bowl) there is a rich history which started with Merchant throwing his partner into the deep end with Indian cinema, with films such as their first collaboration The Householder in 1963, then Shakespeare Wallah in 1965, and Bombay Talkie in 1970.

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala provided the screenplays for the early works and Merchant roped in people such as Indian cinema legends Subrata Mitra and Satyajit Ray in getting the work completed as economically as possible. There is an incredible history just going over those early works, which featured legendary Bollywood actors like Shashi Kapoor and people such as Felicity Kendal in her first screen role – essentially playing a heavily fictionalised version of herself in Shakespeare Wallah.

Director Stephen Soucy has almost unfettered access to James Ivory, who recounts his turbulent relationship with his creative partner and lover, Ismail Merchant. Other interviewees include Helena Bonham Carter, whose career was made (and in her mind also hampered) by 1985’s A Room with a View. A deeply irascible Vanessa Redgrave talks about her work with them on The Bostonians and Howard’s End. An enthusiastic and loving Emma Thompson speaks about how Ismail was the mercurial magician and chaotic haggler who fed everyone but tried his best not to pay them and comparing that energy to James’ calm vision.

So many actors have stood under Merchant Ivory’s umbrella. Samuel West, Julie Christie, Greta Scacchi, Lee Remick, Thandiwe Newton, Nick Nolte, Julian Sands, Daniel Day-Lewis, Rupert Graves, James Wilby, Denholm Elliott, Simon Callow, Maggie Smith, Isabelle Adjani, Prunella Scales (mother of Samuel West), Natasha Richardson (daughter of Vanessa Redgrave), Christopher Reeve, Ralph Fiennes, Paul Newman, Joanna Woodward, Robert Sean Leonard, Kyra Sedgewick, Blythe Danner, and of course, Hugh Grant, whose career they made with Maurice and Anthony Hopkins who both loved and loathed them (he would sue Merchant Ivory for non-payment of wages on a later production).

Despite many successes, including Heat and Dust, multi-award nominated works like A Room with a View, The Remains of the Day (based on Kazuo Ishiguro’s Booker Prize winning novel), and Howard’s End, there were also disasters. Every film was precarious. Their adaptation of Tama Janowitz’s Slaves of New York starring Bernadette Peters was an expensive flop. Later films, such as Surviving Picasso and Jefferson in Paris, were panned for various reasons (the latter being that no-one believed that Jefferson would have an affair with Sally Hemmings). Interpersonal and professional strains led to Ismail and James’ legendary quarrels, which would often happen not quite behind closed doors, in the huge Claverack property in upstate New York where Ruth, Richard, Ismail, and James lived on and off since 1975.

There are quiet pains which James and Ismail didn’t speak of, such as Ruth refusing to adapt Forster’s Edwardian set Maurice (1987) for them and passing it on to another writer. The film that James Ivory is most proud of, because it celebrates gay joy and heartbreak, was seen by Ruth to be too slight to bother with. However, she did create a specific plot point which explains why Hugh Grant’s Clive Durham ends his relationship with James Wilby’s Maurice.

The absence of Anthony Hopkins in the documentary is noted. Yet so many people speak with such love for the men who guided them through. Greta Scacchi, James Wilby, Samuel West, and others, including Hugh Grant, acknowledge how the often-fractious couple created art that reflected their experiences as outsiders looking in.

“Only connect!” is a line from Howard’s End spoken by Emma Thompson’s Margaret Schlegel – an intellectual woman who sits at the centre of Leonard Bast’s poverty and Henry Wilcox’s industrial wealth. Rupert Graves applies this line to what Merchant Ivory were trying to do with their films. Connect people with the vast treasures and tragedies of life while living on the margins. Richard was Ismail’s lover. James took travel writer and novelist Bruce Chatwin as a lover. They shared everything but also lived in heightened jealousy and shifting control. Although they were lovers until Ismail’s untimely death in 2005, their relationship, although known, was never publicly acknowledged until many years later because of Ismail’s religious background.

Merchant Ivory were a family – an often dysfunctional one powered by Ismail’s conman impresario genius, James Ivory’s keen eye which came from his time studying architecture and props, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s fierce intellectualism, and Richard Robbins’ seemingly light but often complex scores combining minimalism with lush symphonies.

“Be true to your nature,” might be one thing that most Merchant Ivory films speak of in earnest. But nature is a force that cannot be controlled nor observed in the same way by everyone. Some of the most indelible characters Merchant Ivory put on screen were crushed by social mores and their inability to tell the truth. Stephen Soucy’s documentary is both frank and elusive. There were many truths to Merchant Ivory and not all of them as palatable or polite as people would garner from their works. But the way the documentary frames their incredibly vast output speaks of a manner in which each person was trying to say something specific about their experience as human beings. Whether as immigrants, queer men, or people who benefited from, but also despised, colonialism. Perhaps, in being citizens of nowhere in particular, they were citizens of everywhere.

Merchant Ivory will be screened at the Palm Springs Film Festival on January 6-13, 2024.