In Last and First Men, composer Jóhann Jóhannsson marries sci-fi storytelling to eastern European statuary, with mixed results.

Tilda Swinton is a very cerebral actor — which is not to say that she is a good actor, nor necessarily a bad one — she gives the sort of performances that make you feel very smart. Whether in a superhero movie or a tiny indie film, she approaches her roles with the same concentrated fastidiousness, and she is often quite unwatchable for it. Her hermetically sealed characters present themselves like snowglobes: complex and curious, but with little access for audiences and her scene partners alike. Sometimes it works to the film’s favour — as in Tony Gilroy’s Michael Clayton and (arguably) Lynne Ramsey’s We Need to Talk About Kevin — but too often her insularity renders films dramatically inert and her characters devoid of humanity.

Which is to say, her performance in Jóhann Jóhannsson’s posthumously released feature film Last and First Men is at once entirely fitting, yet totally catastrophic. Based on Olaf Stapledon’s novel of the same name, she provides the disembodied voice of a far future member of a barely recognisable human race chronicling to us the fate of our species as they await the extinction of all life in our solar system. Theirs is a profoundly alien race, by their count the 18th distinct evolution of humanity: ageless, telepathic, able to withstand the radiation of our expanding sun and the emptiness of space.

The story they tell, based on Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 novel of the same name, is fantastic and bizarre, but the delivery left me cold. Swinton’s narration is flat and affectless, a steadfast refusal to lend an emotive aspect to the world she describes. It is as though she is reading from a textbook — dry and dull as a teacher whose passion has long since left — she talks in facts, descriptions, details; and it is hard for one’s mind not to wonder as in a classroom on a hot summer’s day.

It is almost as if Jóhannsson, a composer by profession, considers the narration not to be separate but instead just one part of the aural landscape of the film. The score is a sparse and eerie thing, which unsettles with persistent electronic drones and a haunting voice choir. When the film first debuted back in 2017, it was with a live orchestral accompaniment, it is only this year that it was first screened with a recorded soundtrack. You are most likely to be familiar with Jóhannsson’s work scoring the films of Denis Villeneuve, his work on Sicario landing him an Oscar nomination.

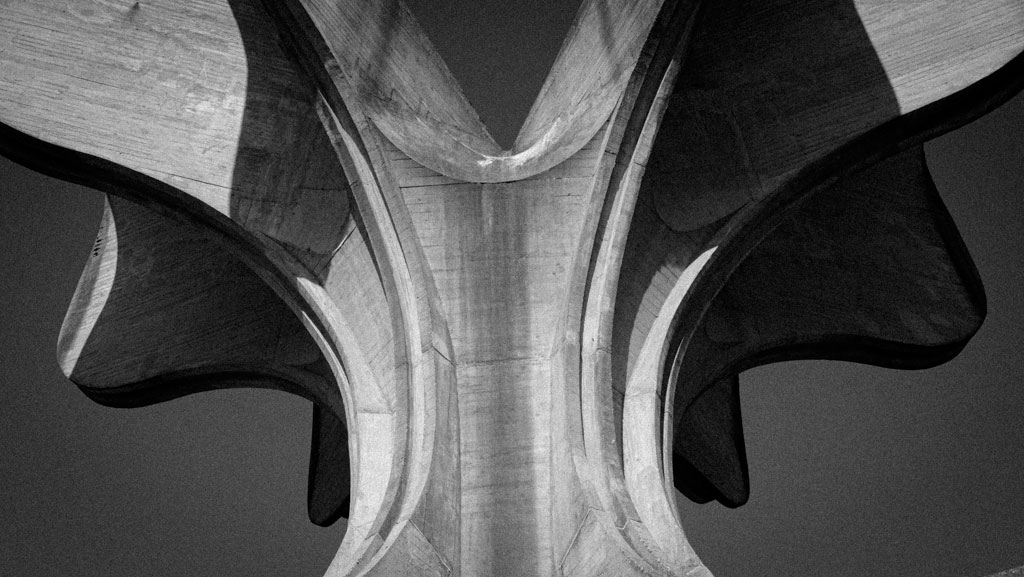

Last and First Men feels like a distillation of his career. Unbounded by traditional narrative, he lets his score drive the story. It speaks of oncoming doom, and wails mournfully for a world soon to be lost. I’ve listened to it several times over since watching the film, it never fails to make me cry. Visually it’s accompanied by black and white photography of the brutalist spomenik statues of the former Yugoslavia. Some are instantly recognisable. Their monolithic and unnatural appearance in remote parts of eastern Europe has led in many cases to their exoticisation. You have undoutably seen pictures of the most famous: the monuments at Podgarić and Jasenovac in Croatia, both appear extensively in the movie.

One can understand why they appear in the film, their forms are striking. Shot on grainy high contrast film, their lines become impressionistic — we see in them cities, stars, spaceships, even the hint of faces. They are framed against cloudy skies, the stark landscapes in which they are located. We are invited to stare into them and consider the society that would build such confounding things.

Of course, we do know. Eastern Europe isn’t Neptune, nor the far future, they were built after World War 2 to memorialise the people’s struggle against Axis powers. They stand on the sites of battles, anti-fascist resistance movements, and former concentration camps. It is impossible to think that Jóhannsson was ignorant of this legacy when making the film. Did he intend for his work to memorialise them too – the thousands of souls who died in the fight against Nazism?

The monuments themselves were constructed mostly in the 1960s, following the former Yugoslavia’s split with the USSR. While a nationwide project the majority were locally conceived and funded, designed to be a uniquely Yugoslavian form of memorialisation: emblematic of their new national identity. It did not last. By the early nineties, the country had dissolved, and the monuments to its legacy fell deeply out of style. It is estimated that hundreds, if not thousands, have been destroyed or lost in the decades since — the ones that remain, chipped and weathered, stand as testament to a vision of the future that will never be.

If all that sounds interesting in theory, it is. The film, however, manages to be somewhat less than the sum of its parts. The ideas at play feel disparate, never quite cohering in a way that feels totally satisfying. Stapledon’s novel is undoubtedly influential and important, Jóhannsson’s score is masterful, and the spomenik are extraordinary works of art. Unfortunately, despite all that, Last and First Men never quite rises to those heights.

Last and First Men was screened at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2020, and was released on BFI Player in the UK on 30 July, 2020. The film will open in theaters and on digital in the US on December 10, 2021, exclusively at Metrograph.