Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is the perfect movie for the Fourth of July, with its rich, summer atmosphere and cynical political commentary.

A movie watching belief that I hold strongly is that certain movies belong to certain seasons of the year. Not just through the particular weather in which the movie takes place, but through the color scheme of its visuals, tonality of the direction, and its thematic concerns can a movie align itself with a specific season. When Harry Met Sally, with its sweater-wearing characters, consistent food munching, and snowy New York City streets, is best enjoyed in the middle of winter. The second part of Chungking Express, characterized by bright yellow, greens and blues, and dreamy pop music is perfect for a fresh, sunny spring afternoon. The steaming cups of cider, falling leaves, and tartan orange and brown of Fantastic Mr. Fox does not evoke the actuality of autumn, but what it is supposed to look like and feel.

Another movie that is able to evoke a specific time of the year is Steven Spielberg’s Jaws. In my humble opinion, there is no more appropriate time to watch than in the corridor around the Fourth of July. It is more than just the fact the film is set around the United States Day of Independence; with the cinematography, the behavior of the characters, and the movie’s commentary on U.S. social and political life that Spielberg is able to perfectly capture the summer holiday. The plot of Jaws would not play out the same way if it was placed at any other time of the year; the holiday determines everything about the movie down to decisions made by the characters.

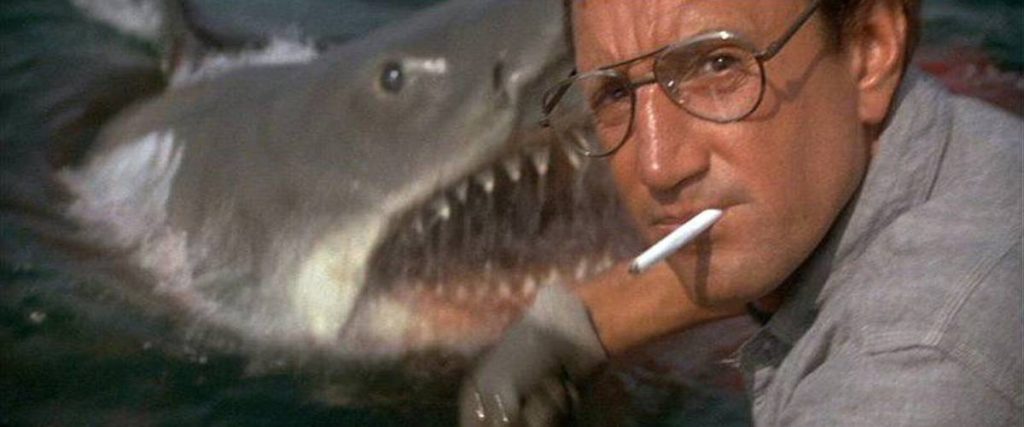

The seminal horror classic Jaws begins when a beautiful young woman is attacked and killed by a Great White Shark off a Martha’s Vineyard-type resort destination, Amity Island. The Chief of Police, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) attempts to protect the community from further deaths by closing the beaches, but is stopped from doing so by Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton), who is concerned about the loss of revenue if tourists cannot visit Amity’s beaches. After a disastrous Fourth of July celebration, Brody sets out with smart-aleck Marine Biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) on the boat of salty fisherman Quint (Robert Shaw).

Jaws is set around the Fourth of July, and throughout the first section of the movie before the action moves to the open seas you are witness to a bustling Amity, full of people celebrating the holiday and participating in all manner of summer activities. The movie opens with a group of college students sitting among the sand dunes of a beach around a bonfire, framed as though they are on a Beach Boys album cover. The feeling of summer is captured in Jaws through the sight of people listening to the radio and drinking Coke while sunbathing, the kayaks and speed boats that litter the glistening waters of Amity Island, the high school marching band practicing John Philip Sousa marches, the sight of sun burnt and sweat-stained people clad in denim shorts and bandanas. While watching Jaws, you can smell that sunscreen, beer, and fish in the air.

Many horror movies utilize negative space in their cinematic images in order to create tension for the audience, but in Jaws, Spielberg crowds his frames with people. Jaws is a full movie: rich and densely textured, with multiple layers to every shot. As Alex Kintner’s mother inspects his fingers on the beach children run in front of the camera, fishermen carry on their own conversation in the back of the frame as Brody and Hooper debate whether a Tiger Shark could be the killer. During the meeting of Amity town leaders and business owners, people talk over one another as though it was a Robert Altman production. These effects create a real sense of community with Amity Island. It creates an atmosphere and set of behavior that is recognizable for the viewer; Amity becomes like the place where they live.

Isn’t community a significant part of the fourth of July? You see your neighbors more often during the summer than at any other time of the year; at firework displays or block parties, both staples of Fourth of July celebrations, or at the park, at the local swimming pool or beach, having a barbecue, hosting a lawn party, going on a walk, or just sitting on the front porch. People are outside more often during the summer, people are seen more often during the summer. Through the dearth of extras dotting Jaws, and the use of overlapping, layered dialogue, Spielberg is able to capture this particular quality of summer.

Throughout Jaws, large swathes of people are able to spend time at the beaches of Amity Island instead of being at work or taking care of other pressing responsibilities. Men gather on the docks guzzling beer, women lay on the beach reading, teenagers take to the water in sailboats, children run around the sand dunes. This leisure time, this freedom from responsibility, is a symbol of summer, traditionally a time for vacations and respite from the school year.

Jaws is a movie that works on two levels. Its outer shell is that of an entertaining creature feature that manipulates its audience’s reactions as deftly as Hitchcock. Woven throughout the thrills and scares is a political thread inspired by Henrik Ibsen’s play “An Enemy of the People,” one that is not flimsy, tossed-off, or accidental, but given great consideration by the filmmakers. It is this political thread that, in my opinion, turns Jaws from a b-movie monster flick into a masterpiece, as it hides vitamins and nutrients in among the fast food pleasure of shark attacks. It provides the audience with something human and universal to hold onto in the midst of spectacle. Nearly fifty years later, the Mayor from Jaws is still used as an example in political commentary, because he represents something that will always be true about capitalism and government.

In a 1973 interview with Dave Pirie, a pre-Jaws Spielberg, discussed his movie Duel, articulating his view on middle class America. “It begins on Sunday. You take your car to be washed. You have to drive it, but it’s only a block away. And, as the car’s being washed, you go next door with the kids and you buy them ice cream at the Dairy Queen, and then you have lunch at the plastic McDonald’s […] And by that time you go back and your car’s all dry and ready to go and you get into the car and you drive to the Magic Mountain plastic amusement park and you spend the day there eating junk food.

Afterwards, you drive home and the wife is waiting with dinner on. And you have instant potatoes and eggs without cholesterol, because they’re artificial – and you sit down and you turn on the television set […], which is pabulum and nothing more than watching a night light. And you see the news at the end of that, which you don’t want to listen to because it doesn’t conform to the reality you’ve just been through primetime with. And at the end of all that you go to sleep and you dream about making enough money to support weekend America.”

In Jaws, Amity Island is ‘weekend America’ made manifest. It is a pleasure palace dedicated to weekend excursions, hotel stays, boat sailing, beach going, junk food and beer. As the shark attacks reveal ‘weekend America’ is built on a shaky, dangerous foundation. As Chris Auty described in a 1981 essay for Sight and Sound, “This is Eden on the eve of the Fall.” For children ‘weekend America’ is an amusement park, a play that will never end, but for the adult, it is something that will never truly exist.

Mayor Vaughn refuses to let the beaches be closed because “Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars. If the people can’t swim here they’ll be glad to swim at the beaches of Cape Cod, Hampton, Long Island.” In the town meeting, business owners, dependent for their livelihood on tourism, spend their energy yelling about how long the beaches will be closed instead of finding a way to get the shark out of their waters. As a result of Amity Island’s Mayor and business owners’ desire to keep the beaches open for capital gain, more deaths occur. In Jaws, vacations and leisure time are built on the suffering and exploitation of others.

On Amity Island, in order to celebrate the Fourth of July, death needs to occur, from the Kintner boy to man with the canoe in the estuary to the residents of Hiroshima and American servicemen invoked by Quint’s “Indianapolis” speech. In Jaws, a celebration of the Fourth of July is tenuous at best and impossible at the worst. This bleak, cynical, thought-provoking look at the holiday makes Jaws the definitive Fourth of July movie.

Jaws is now available to watch on digital, on demand, and on 4K Ultra HD. Read our reviews of Jaws below!

Loud and Clear Reviews has an affiliate partnership with Apple, so we receive a share of the revenue from your purchase or streaming of the films when you click on the button on this page. This won’t affect how much you pay for them and helps us keep the site free for everyone.